James

Thomas of Catasauqua and the Alabama Iron Industry, 1872 - 1879

By John B. McVey

FOREWORD

This

monograph is one of a series of three publications dedicated to the history of

the Hopkin Thomas family of Catasauqua, Pennsylvania.

Hopkin Thomas was a Welsh-trained engineer who emigrated to America in 1834 and who pursued activities in

the Philadelphia locomotive shops, the anthracite mines of Northeastern Pa.,

and the anthracite iron furnaces of the Lehigh Valley. He was associated with

David Thomas; a fellow Welshman who followed Hopkin

to America in 1839 and who gained prominence as the iron master who first

successfully used the hot blast technique to produce iron in commercial

quantities using anthracite coal in America.

Hopkin Thomas and David Thomas were not

related. This fact is sometimes confused in the histories written about the

locales where Hopkin Thomas' achievements impacted

community life.

My

interest is in the technical accomplishments in which Hopkin

Thomas had a hand. Being a

fifth-generation engineer in this technically oriented family, it was natural

for me to be attracted by the technology of that time period - the nineteenth

century.

Although

I grew up in Catasauqua in the house that James Thomas, son of Hopkin, presented to his daughter as a wedding present, and

although my grandmother, Ruth Thomas McKee was still active and vital during my

youth, no oral history of Hopkin or James was

presented to me at that time. Indeed, almost all of the information presented

in these volumes is derived from published histories that I began to research

beginning in Wales in 1995. This monograph and the companion volumes dealing

with Hopkin Thomas' technical career and the Hopkin Thomas family genealogy are necessarily incomplete. I

would ask that readers who have additional information to share please contact

me at the address below.

John

B. McVey, ScD.

PO

Box 397

Jackson

NH 03846

jb.mcvey@roadrunner.com

INTRODUCTION

The

histories of the Lehigh Valley, Pennsylvania recount

the many accomplishments of James Thomas, (see biography)

son of Hopkin Thomas.

To wit, the establishment of the Davies and Thomas

iron foundry in Catasauqua, the electrification

of Catasauqua and environs, and his leadership in

the building of the Grace Episcopal Methodist Church.

His activities during the decade that he

spent in the Jones Valley of Alabama, present-day

Birmingham, are only lightly touched upon. Likewise

the many rich, in-depth histories of the Alabama

iron industry, while acknowledging his presence

along with the presence of other members of the

Thomas families of Pennsylvania, can benefit from

a more precise account of these activities of these

men.

At

the time of this writing (2017), Birmingham, Alabama is a booming metropolis.

In 1870, Birmingham did not exist. In fact in a mere 50 years Birmingham grew

from a hamlet into a city of industrial might. How could this happen? The

answer is that the Jones Valley and Jefferson county where Birmingham grew was

blessed with all the natural resources necessary for the production of iron and

steel. The accomplishments of the individuals who were prime movers in this

growth must have interesting stories to tell. This, together with the fact that

southerners have a great sense of history derived from the trauma wrought upon

them by the Civil War of the 1860s, has led to the publication of many

excellent histories of the area.

One

of the most fascinating. of these histories is that of

Ethel Armes who wrote The Story of

Coal and Iron in Alabama in the year 1910. In addition too being an

accomplished historian, Ms. Armes had the benefit of

being acquainted with many of the descendants of the principals in the story.

As a result, her volume is filled with recollections and biographical insights

on these people - material not generally found in historical documents. No

record of history is perfectly accurate, and, indeed, family member recollections

are sometimes faulty. Historians are aware if an erroneous statement is

repeated several times it is eventually assumed to be fact. One of the goals of

this publication is to correct a few of the inaccuracies regarding the Thomas

families of Pennsylvania that have propagated through several of the histories.

THE THOMAS FAMILIES OF

THE PENNSYLVANIA IRON INDUSTRY

As

noted in the Foreward, there were two Thomas families

from the Neath area of Wales that were involved in the

development of the anthracite-fired iron industry in Pennsylvania in the 1800s

- Hopkin Thomas and David Thomas. As far as can be determined, these

families were not related. Hopkin was born in 1793 in

Bryn Coch and David was born in 1794 in Cadaoxton.

Nearby was the Neath Abbey Ironworks close to the Neath River. The family histories do not indicate

that Hopkin and David were friends in their childhood

years, but they certainly got to know one another in their teenage years as

they both were trained at the Neath Abbey Ironworks.

Hopkin and family emigrated to

America in 1834 and settled originally in Philadelphia, PA where his son James

Thomas was born in 1836. David

Thomas and family emigrated to America in 1839 and

settled at Catasauqua on the Lehigh River where he founded the Crane Iron

Works. David had a son Samuel, born in 1827, who was also in involved in the

Birmingham iron industry at a later time -- after 1866. But the subject of

this monograph is James Thomas who went to Alabama in the year 1872.

Map of the Neath area of Wales. Bryncoch is

at top, Cadaxton in middle right, and Neath Abbey at

lower left.

When

Hopkin and David were in America it was clear that

they communicated with one another using the postal service, but none of those

letters are known to exist. Indeed, as Hopkin's

career developed, he eventually became the Chief Engineer at the Crane Iron

works and the two families lived within a block of one another in

Catasauqua.

THE ALABAMA LINK

The

link between James Thomas and the Alabama iron industry was through a Welsh

ironmaster named Giles Edwards.

Giles Edwards

Giles Edwards was a Welsh immigrant, trained in the iron-making business of Europe, came to America in 1842 and worked at iron plants in Carbondale and Scranton, PA and then worked with Hopkin Thomas at the Thomas and Ollis Machine Shop and Foundry in Tamaqua, PA. After the Great Flood of 1851 destroyed that iron foundry, both Hopkin and Giles moved to Catasauqua, where David Thomas and the Crane Iron Works were located. Hopkin became the Chief Engineer at Carne Iron and Giles held various positions until his health began to fail and he moved south. (See Giles Edwards, Alabama’s Leading Proponent of Coke as Furnace Fuel by Jim Bennett. Also, in Sources and References see Armes, Ethel, The Story of Coal and Iron in Alabama, a. Giles Edwards for further details. But none of these sources indicate that when Edwards was in Tamaqua working at The Thomas Iron Foundry, it was Hopkin Thomas, not David Thomas, that Giles Edwards was working for.)

Giles

Edwards first went to Chattanooga, TN in June 1859 where he worked on the Bluff

furnace that was being remodeled from a charcoal furnace to a coke furnace. It

was a success, but the Civil War broke out in 1860 which

resulted in most of the iron-making industries in the South being suspended.

It

was during this time that

Bill Jones, a very good friend of James Thomas,

visited the Edwards family, accepted a position

of master-mecahnic under Edwards and stayed for

a number of months until the Civil War broke out.

So the contact that the Hopkin

Thomas family had with the iron industry of the

South was through both Giles Edwards and Bill Jones.

It

was in the spring of 1862, at the request of Judge Lapsley

of Selma, Alabama that Giles Edwards went to Selma and became familiar with the

iron resources and foundries in that state. Edwards was responsible for

reconstructing the Shelby Iron Works which then

operated continuously throughout the Civil War until it was destroyed in April

1866 by Wilson's raiders. (Armes, p. 177)

Map of Alabama showing the furnace sites

that are mentioned in this article.

The city of Birmingham is located just above the Oxmoor

and Irondale Furnaces. (From Bennett, p. 10)

After

the conclusion of the Civil War, in about the 1866 time period, Edwards

contacted David Thomas regarding the mineral lands in the Jones Valley. David,

his son Samuel, and grandson Edwin came to Elyton,

Alabama (which later became part of Birmingham) and had discussions with Baylis Garace who they retained

as their agent, and they purchased land for Edwards to use near Tannehill. But

the Thomas's themselves did not get involved at this time..

(Armes, p. 212)

Giles

Edwards continued to make land purchases and on

Dec. 30, 1868 the Pioneer Company was formed with

David Thomas, son John Thomas and Giles Edwards

among its organizers. (Bennett,

p. 83). Further details on the purchases

by David Thomas are found in Bennett, Tannehiill

and the Growth of the Alabama Iron Industry,

p. 238. It was not until 1886 when Edwin Thomas,

son of Samuel Thomas, went to Alabama with his father

to design and erect a plant for the Pioneer Company

and continued there until 1899 as president of the

Pioneer when the plant was sold to the Republic

Iron and Steel Co. (Wint,

p. 82)

JAMES THOMAS GOES TO

ALABAMA

There are two

things that we know about Giles Edwards:

(1)

He was familiar with the coal and iron ore resources of Alabama

(2)

He was in contact with those involved in the anthracite iron-ore business in

Pennsylvania.

With

respect to the 2nd item, we know that he was friends

with the members of the Hopkin Thomas family. Hopkin and

wife Catherine Richards had two sons and three daughters. One son was James Thomas, the other son was William R. Thomas. Daughter

Catherine Maria married James Wheeler Fuller, Jr. Daughter Mary married James Harper

McKee. James W. Fuller together with

James H. McKee formed the Lehigh Car, Wheel and Axle Works in Fullerton Pa in

1866, it was reorganized as the McKee, Fuller Co., but continued to trade under

the original name. Both James Thomas and William R. Thomas were involved in

this company. So when the McKee,

Fuller Co. was approached by Alabama interests about getting involved in

resurrecting the local furnaces (see below), there is no doubt it was the

doings of Giles Edwards that brought about this connection.

The

most accurate account of how James Thomas got involved in the Irondale Furnace

in Jefferson County, Alabama is given in an unpublished manuscript entitled

"Cahaba Iron Works and Its Successors"

by Robert Yuill, a historian who did substantial work

on the Irondale Furnace. Briefly,

the following activities are noted.

Wallace

S. McElwain and others

constructed the Cahaba Iron Works, also referred

to as the Irondale Furnace in 1863. The furnace was

destroyed by Union troops in early 1865.

After the war had ended, McElwain

and A. D. Breed of Cincinnati, OH secured the capital

to resurrect the furnace in early 1866. The furnace operated

until about 1870 when the Jefferson County Probate

Records indicate that the property was leased to

the

McKee, Fuller and Co. in May

of 1871.

There

is no indication of how the McKee, Fuller Co. had been notified of the

availability of this Alabama furnace, but it is my opinion that this was the

result of Giles Edwards contacts. In any event, James Thomas, who at the

time was superintendent of the Carbon Iron Works in Parryville,

PA and who was involved in the McKee, Fuller Co., volunteered to come to

Alabama and assume the position of General Manager of the Irondale

Furnace. Thus, in 1872, James

Thomas, wife Mary Ann (nee Davies), daughters Blanche (age 7), Mary (5) and

Ruth (1) and son Rowland (3) took a train ride from Parryville,

PA to Jefferson Co., AL. The

exact location of their home has not been identified. James and Mary Ann had three more

children while they were in Alabama - Helen (b. 1872), Catherine (1874) and Hopkin (1876).

The

original lease was for a period of five years. When

James Thomas arrived at Irondale, the furnace was

run in the 'as received' state and it was determined

that the hot blast was ineffective. According to

Yuill's account,

James Thomas made a number of changes

to the furnace; perhaps the most important was the

installation of his automatic bell and hopper for

closing the tops of blast furnaces, for which he

received a patent

in 1870. This allowed the use of the hot furnace

gases that with an open top furnace are wasted,

to be used to provide a hot blast. With this arrangement,

the hot furnace gases were sent to a heat exchanger

called a Stove in the furnace industry. The stove

was heated by the furnace gases and indirectly heated

the blast wind. Eventually, three brick stoves were

built. These modifications enlarged the furnace

from a 40’ height to 46’ the bosh was 10’ 6” in

diameter. The method of charging the furnace was

also changed; previously to get the raw materials

to the furnace wagons were used to haul the iron

ore, charcoal and limestone to the top of the furnace.

To eliminate this expense a water elevator, or water

hoist, was used to raise the required material to

the top of the furnace. The new hot blast stove

system raised the output significantly, to 15 tons

per day.

At

the expiration of the five-year lease, the Irondale Furnaces ceased operation. James Thomas then went to the Oxmoor Furnace operation where he was General

Manager. Again, it is not known

whether James Thomas and family moved to a new home near Oxmoor,

but that was probably the case.

It

was fairly clear that the Oxmoor Furnaces were used

to further develop the concepts of a coke-fired furnace developed at Irondale.

The location of the Oxmoor Furnaces placed them very

close to the South and North RR, providing good transportation of raw materials

(coal and limestone) and finished goods. Iron ore for the Oxmoor

Furnaces came via tramway from the mines on Red Mountain about 2 miles north of

the furnaces.

The

most accurate published account (although not perfect)

of the activities at Oxmoor is given in the Woodward

Iron Company text.

In effect, James Thomas, who remained at

Oxmoor until 1879, had

the responsibility for convincing the local capitalists

of the promising resources of the Jefferson County

area as well as directing the reconstruction of

the blast furnaces so that coke iron could be produced. Both Furnace

#1 and Furnace #2 were rebuilt and the first coke

iron using the county resources was produced. Transportation

issues were significant; railroads needed to be

completed. The general economy was in a slump. At

one point, James got his brother, William R. Thomas,

to come to Alabama for a brief stay to get the Helena

Coal Mines to improve their production. My recollection

is that James Thomas, who is best remembered as

an engineer, got tired of the efforts of raising

the capital necessary to further improve the Oxmoor

Furnace and when contacted by partners at the Lehigh

Car, Wheel and Axle Works in Pennsylvania regarding

reforming the Davies

and Thomas Co, in Catasauqua, Pa, he accepted

that role and left Alabama in 1879.

However, the coal and iron industries in

the Birmingham area had now been vitalized and continued

to thrive to the present time.

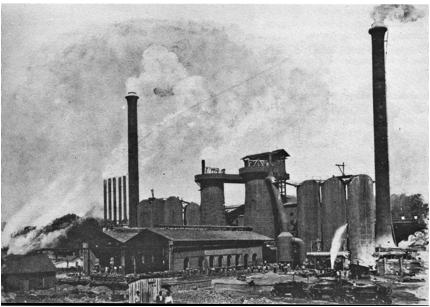

The Oxmoor

Furnace where the first pig iron made with coke

in 1878. (From McMillan,

p.26)

REMBRANCES OF JAMES

THOMAS

While

examining the records of the iron industry in the Birmingham area, I was struck

by three articles regarding James Thomas.

First there is Mary Gordon Dufee's Alabama Sketches which appeared as a series of newspaper columns in

the Birmingham papers in the late 19th century. This excerpt is from Sketch 40,

found on Page 162 of Vol. 2 of the collection contained in the Birmingham

Public Library.

ALABAMA

SKETCHES

James

Thomas, Pennsylvanian by birth, came, in the prime of early manhood, to help

develop the mineral interests of the valley when the gloom of war's destruction

yet lingered over its fair face, and the task seed hopeless. In personal

appearance he was about the average in height, perhaps a little taller, fair

complexion, dark hair and eyes; in temper, firm, and steadfast; in manner,

plain and unassuming, with not a trace of vanity or haughtiness; in mind, very

intelligent and cultured; and in. his private life a moral, Christian

gentleman, laboring with an unwearied zeal for the establishment and promotion

of Sabbath schools and churches, and sustaining their influence by the example

of his own blameless life; indeed he was so popular that the most rabid

southerner would have voted him into any office he might have wished. His first

tern of service was as superintendent of the Ivorydale

(Ed., Irondale) furnaces, and subsequently the Eureka Company, at Oxmoor; in both positions he displayed signal ability,

prudent management, and tireless energy, finding time amid his numerous duties

to elevate the moral tote of the community. In these praiseworthy objects he

was aided by his accomplished wife, herself a devoted Christian lady. Mr.

Thomas was a nephew of the celebrated David Thomas, of Lehigh Valley, Penn.,

and a cousin of the Thomas now engaged in erecting iron furnaces on the old Williamson

Hawkins plantation; themselves deservedly and gratefully known in Alabama for

their early and abiding faith in the solid resources and future of the mineral

region. (Ed., James was the son of Hopkin Thomas,

unrelated to the David Thomas family). Family ties and business advantages

induced him a few years ago to return to his native state, and it cost him no

small effort to bid adieu to the gulf state, whose welfare he had so such

advanced and whose warn-hearted people he so lovingly appreciated; they, in

return, feelingly and sorrowfully parted from him as one who had indeed,

"proved a friend in need", and from the first won their esteem by his

manly bearing, industry and sympathy for them. It s a constant an favorite

remark of Mr. Thomas' that he believed, when fully investigated and developed,

Jefferson county would prove to be the richest county in mineral deposits in

the entire United State; arid time seems to be demonstrating the truth of his

theory and the wisdom of his faith. To his indefatigable labors and their

results much is due in the founding of the city of Birmingham, as it was to him

all distinguished visitors were referred, and his statistics upon the ores and

their wonderful richness form pert of the most valuable of the tabulated data on

that important subject.

The

second article was a letter from Oxmoor that appeared

in the Birmingham Iron Age, Birmingham, Ala., April 3, 1878, W & Chas.

Roberts, Publisher. You need to know that James Thomas, his wife and seven

children were ardent church-goers. Indeed when James returned to

Catasauqua, PA he was responsible for building the Methodist church at that

location.

LETTER

FROM OXMOOR

Ed.

Iron Age: I stepped into the church last Sunday at the hour of 10 a. m. and was

astonished to find the house crowded with old, middle-aged, young and little

folks attending Sunday school. Rev. Mr. Hill, pastor, and Mr. James Thomas,

Superintendent, with their never tiring energies have succeeded in building a

very fine Sunday School at this place, and judging from what I saw they have a

very fine library. Misses Thomas, Hanby and Stephens

are the young ladies who raised the funds ($150) for its purchase. All honor to

women’s energy.

I

believe you are church going men

(If you are not you ought to be.) It would do you good to be at Oxmoor on Sabbath and see the congregation that attends

church. I say without fear of contradiction that there is not a better-behaved

one in the State.

There

are about 4000 tons of iron on the yard, sold, waiting

to be shipped, and the Company has orders for 7,000 tons more ahead. Mr. James

Thomas, Superintendent of the Eureka Company, deserves great credit for the

manner he has managed the affairs of the Company, and built up such mammoth

works. It is a great pity that we haven’t more Jim Thomas’ in the county. He is

one of the most high-minded, public-spirited men in the South. Through his

energy and public spirit, with the help of others, we have one of the best

schools in the County with Capt. R. H. Pratt as principal.

The

third article is from the publisher of the Birmingham Iron Age subsequent to

the success at the Oxmoor Furnace.

Birmingham

Iron Age, Birmingham, Ala., Thursday, April 6, 1876.

W & Chas. Roberts, Publisher.

For about fifteen years the iron interest

of Jefferson County has been attracting public attention. Up to 1860 the iron

lands of this vicinity were unnoticed and uncared for. In 1862 these lands

assumed a sudden importance on account of the necessities of the war, which

closed southern ports and shut out the supply of foreign iron from our people.

In that year, John T. Milner and others, purchased 100 acres of land on the

west side of Grace’s Gap, at the price of $8,000. On this or near the Red

Mountain Iron Company established the first blast furnace in this county. About

the same time, W. S. McElwain located at Irondale,

and by extraordinary energy succeeded in starting another furnace before the

Red Mountain Company were quite ready to go into

blast. The Red Mountain … unintelligible … McElwain

was the first to make iron. Millions of Confederate money were

expended on these enterprises, when in April, 1865, Wilson’s raid destroyed

their machinery and burned everything about them except the stacks. In 1866-7 McElwain revived the furnace, but failing financially, it

was leased to McKee, Thomas & Co., (ed, McKee, Fuller

& Co.) of Pennsylvania under the superintendence of James Thomas until

1875, when they suspended work in order to make a new organization for the

purpose of testing the use of coke from the native coals in the manufacture of

iron. In the meantime the Red Mountain Company suffered their work to remain in

ruins from their destruction, in 1865, until 1872, when they re-organized,

under the presidency of Danl. Pratt. The works were rebuilt and put into

operation in 1873 when this company went down under financial pressure. Last

year a new company, consisting of J. W. Sloss, James

Thomas and brother, E. D. Standiford, H. V. Necomb, Caldwell, Miller and perhaps others, with the

purpose of adapting one of the charcoal furnaces at Red Mountain to the use of

coke. Of this, Col. Sloss was elected president and Mr. Thomas Superintendent,

and under their directory the changes were made. On the 11th of

March, 1876, the blast was put on, the furnace being charged with native coke

from the Cahaba coal mines, red hematite and limestone from Grace’s Gap, and

the first iron was made on this county by the use of coke. The

result was watched with deepest interest by all iron men in this State,

and many in distant States were informed by telegraph of the first runs made

from the works. The effort was perfectly successful from the beginning owing to

the excellent arrangements which had been perfected by Mr. Thomas, but it was

not until last week that the full capacity of the furnace could be tested, the

proportion of iron to coke having been continually increased until it is now

about 30,000 pounds of coke to 45,000, and 1200 pounds of limestone. This

charge gives a product of 30 tons of iron per day, and the quality is said to

be the best ever made from red ore.

Now what may we expect to grow out of the

success of this experiment? We are

told that this iron can be shipped to New York and sold at a cost less than

Pennsylvania iron, and yield a handsome profit. It cannot but be that this fact

will cause a universal excitement among the maker of iron in the United States.

It is believed by men in a position to understand that millions of dollars will

be invested in our country before the end of this year. The great hopes that

have long been entertained by our population, but which have been so long

deferred as to make our hearts sick, may now be realized within a reasonable

time. Who would not rejoice to see such men as Peters, Goodrich, Powell, Thomas

Caldwell, Sharpe, and others, who have invested so much labor and anxiety, to

say nothing of capital, in our lands, rewarded with an overflowing bounty. And

then there are thousands of others who have located in our valley with this

hope prominent in their prospects, who will now be

blessed by its realization. We want Peters and his men to have a big bonanza,

and to eat out of silver plates, etc. like the bonanza kins

of California; but we also want to see every other man rewarded according to

the measure of his patience and faith in our mineral resources.

Sources and References

Alabama

Blast Furnaces, Woodward Iron Company, Woodward Alabama, 1940.

Oxmoor Furnaces, pp

106-110.

Armes, Ethel, The Story of Coal and Iron in Alabama, Facsimile Edition, Bookkeepers Press, Birmingham, Alabama, 1972. (Original ed. Pub. 1910)

Barefield, Marilyn Davis, A History of Mountain

Brook, Alabama, Birmingham Publishing Company, 1989

Bennett, James R., Old Tannehill,

A History of the Pioneer Ironworks in Roupes Valley

(1829 - 1865), Jefferson County Historical Commission, 1986

Bennett, James R., Tannehill and the Growth of the Alabama

Iron Industry, Including the Civil War in West Alabama, Alabama Historic

Ironworks Commission, 1999

Bennett,

James R. and Karen R. Utz, Iron & Steel, A Guide

to Birmingham Area Industrial Heritage Sites, University of Alabama Press,

2010.

Bennett, Jim,

Giles Edwards, Alabama's Leading Proponent of Coke as Furnace

Fuel, Newsletter of the Birmingham-Jefferson Historical Society,

April 8, 2010

Lewis, W. David,

Sloss Furnaces and the Rise of the Birmingham

District, An Industrial Epidemic, The University of

Alabama Press, 1994

McMillan,

Malcom C., Yesterday's Birmingham,

E. A. Seemann Publishing, Inc., Miami,

FL, 1975

McKenzie, Robert

H., Reconstruction of the Alabama Iron Industry,

1865 - 1880, The Alabama Review, A Quarterly

Journal of Alabama History, July 1972, Vol.

XXV, NO. 3, pp 178-191

White,

Marjorie Longennecker, The Birmingham District,

An Industrial History and Guide, Birmingham Historical

Society, 1981

Wint, Dale Charles, A

History of The Iron Industry and Allied Businesses

of The Iron Borough, Catasauqua, Pennsylvania,1993.

Yuill, Robert, Cahaba Iron Works and Its

Successors, Unpublished.