Excerpts from

A HISTORY OF

MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA

&

INCIDENTALLY OF SHADES VALLEY

by

MARILYN DAVIS BAREFIELD

1989

Copyright 1989

Southern University Press

SET UP, PRINTFD AND BOUND IN

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

FOR

SOUTHERN UNIVERSITYY PRESS

AT THE PRESS OF BIRMINGHAM PUBLISHNG

COMPANY

130 SOUTH 19TH STREET

BIRMINGHAM, AL 35233

CHAPTER III

CAHABA IRON WORKS

The Cahaba Iron Works is the most historically significant place in Mountain Brook. It is, perhaps, better known as the Irondale or McElwain Furnace or Jefferson Iron Works and is familiar to the children in Shades Valley by the name of the "Old Cannon Ball Factory," although no cannon balls were ever produced there. This furnace went into production in 1864 under furnace master, Wallace S. McFlwain

McElwain, born in Pittsfield, Massachusetts in 1832 and his wife, the former Cornelia G. Towne a native of New York, had two daughters, Ida T. (Mrs. J.E. Hensley) and Alice B. (Mrs. Hubert J. Miller). McElwain trained to be a machinist, working for a while in a gun factory in New York, and later moving to Sandusky, Ohio where he worked in a foundry and machine shop. At the instigation of his uncle, Walter L. Goodman, President of the Mississippi-Central Railroad he moved to Holly Springs, Mississippi in 1859. Goodman, a native of Ireland, at that time was overseeing construction of the railroad. McElwain soon induced two men connected with the railroad, Wiley A.P. Jones and Capt. E.G. Barney, to join him in the foundry business under the name of Jones, McElwain and Company. Jones, from North Carolina, was a grader with the railroad, and a man of financial substance. Capt. Barney, superintendent of the railroad and a native of New York, had even greater financial resources with a value of $36,100 in real property and $39,000 in personal property as listed in the 1860 Census. Jones contributed enough lumber for construction of the work sheds, while Capt. Barney donated an old locomotive boiler he fished out of the Tallahatchie River. McElwain, with his brains and New England ingenuity, fashioned a cupola out of the shell of the boiler and on completion of the shed was in business.

22 A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA

With his uncle throwing orders his way when possible, it was not long before McElwain enlarged his works to include a pattern shop, foundry and blacksmith shop. Within 18 months from the time the plant went into production, business had increased to the point that when the call went out for bids for the beautiful and intricate iron work of the Moresque Building in the French Quarter of New Orleans, McElwain placed a bid and was selected over firms in Philadelphia, Pittsburg, Cincinnati and New Orleans. For many years a plaque inscribed "Made by the Jones, McElwain, and Company Iron Foundry in Holly Springs, Mississippi" was attached to the building. As a result of this distinction the Holly Springs firm soon received an increasing number of contracts from Mississippi, Louisiana, and Kentucky. Some of the ante-bellum homes in Holly Springs today have porches accented with his delicate iron work; others have his iron fences and gates surrounding their yards; and many of the family plots in the local cemetery are rimmed with graceful iron fences, each one seemingly different from any of the others and created by McElwain or his assistant/Merrell.

In 1860 McElwain acquired another partner, J. Howard Athey, Transportation Agent with the Mississippi-Central Railroad, who resided with the M.M. Merrell family in Holly Springs. Athey purchased half of Jones' interest and business flourished. By the spring of 1861 as many as 200 men were employed in the foundry including an all-night work force. McElwain and Merrell built their own machinery and designed all their patterns which they sent to other foundries in the state for completion.

That year McElwain received proposals from the Confederate government to convert the foundry into an armory for making small arms and cannons, with an advancement of $60,000 from the government for the delivery of 20,000 rifles and 10,000 muskets slated to begin in November. This funding enabled him to enlarge the foundry with construction of a two-story building 200 feet long and 50 feet wide and a huge blacksmith shop with 30 forges, strip hammer and rolls for the manufacture of gun barrels, and gave the firm the further distinction of being the first armory to produce small arms for the Confederacy under contract. The first guns manufactured were not too successfully executed as some of them were returned for repair. The first gun made for the Confederacy, among those

24 A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA

returned, is now on display in the Franklin County Museum in Holly Springs along with memorabilia of the "Rebel Armory," the name by which the furnace is most commonly known today. Cornelia McElwain later related how she assisted from time to time when the men were pouring the ladles of metal into the cannon moulds.

By early 1862 McElwain knew that it was only a matter of time before the Union troops reached his section of Mississippi. With his Holly Springs foundry producing arms for the Confederacy, it would be one of the major targets for destruction. On April 23, 1862 an Indenture was recorded in the Marshall County Courthouse whereas the Confederate States of America paid Jones, McElwain & Co. $150,000 for all their property in Holly Springs together with all the Armory and Foundry buildings and all improvements of any kind thereupon, all the machinery, tools, materials and effects of any kind which the parties owned and possessed in connection with the Armory and Foundry.

McElwain immediately began making plans to move operation to a safer locale. On February 22, 1863, McElwain purchased his first piece of land in Jefferson County, Alabama acquiring approximately 80 acres from Willis F. and Martha Eastis and began construction of the Cahaba Iron Works. Other land was purchased from John S. and Sarah D. Poole,

A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA 25

Obadiah W. and Susan C. Wood, William Cummins and Henry Shackelford and others until he had amassed a total of 2,146 acres. This land included two detached sites on the Cahaba River and extended otherwise from present day Spring Valley, Westbury, and Cherokee Roads on the south to Red Mountain on the north; from as far west as Montrose Circle to near the eastern end of Brookwood Road. Found on this land were rich deposits of coal and iron ore with a good supply of hard wood for making charcoal, within easy reach of limestone, all prerequisites for making pig iron. The ore for the furnace came from a site near the eastern end of Red Mountain on land purchased from Obadiah Wood. The part he mined lies east of Baptist Montclair Hospital and north of the intersection of Hagood Street and Montclair Road* When McElwain worked the ore, he harvested the lodes of "soft ore" or red hematite, located on the surface of the mountain with the limestone for fluxing purposes coming from the same neighborhood. The tramway from the mining site to the furnace went along the route of Hagood Street to what is now the Crestline Park shopping center and from there directly across to Leech Drive and then down Leech crossing Shades Creek at its intersection with Furnace Branch, a distance of about one and one-half miles This route also shows up in deeds in probate court referring to the right-of-way of McElwain's tramway. Eighteen year old Sarah Latham watched the Union soldiers march along the tramway past her home on their way to destroy the iron works and many years later she shared the story time and time again with her grandchildren.

*This site is in conflict with most accounts of McElwain's mining activities which say his coal came from the Helen Bess Mine. The land McElwain owned on Red Mountain was further to the east, andit makes no sense to think he would own land on one part of the mountain and dig his ore from a site to which he did not have title.

One of Sarah's grandsons, Earl Jowers, hunted on the mountainside where the mines were located until the development of that neighborhood, and he remembers seeing the mining scars and tramway rails that were left behind. He said there was a huge outcropping of limestone in the general area of the the new shopping center now being constructed on Crestwood Blvd. Now all traces have been destroyed.

As was the custom in plants where there was a commissary, the workers were paid in "script," which they used instead of money when purchasing items in the company-owned store. Script and clacker, company money and coins, came in different shapes and denominations, depending on the company's choice, and with it workers purchased food, clothing, tobacco products or anything else the store had available. McElwain also used this

26 A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA

mode of payment, which was especially helpful in an area where no other stores were available.

Teams of oxen or mules hauled the empty cars to the mine entrance and, when filled, the cars rolled back down the tracks to the furnace under their own power. The stone used in construction of the furnace might have been quarried from the same site worked by Richard Bearden on Montclair Road opposite the entrance to the Baptist Montclair Hospital only a short distance from the tramway.

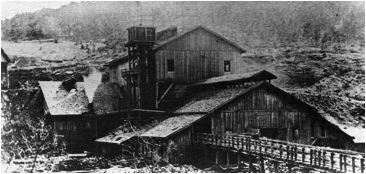

Cahaba Iron Works. George Gmdon Crawford Collection, Samford University.

A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA 27

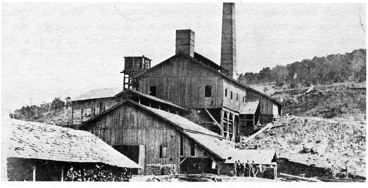

Cahaba Iron Works. George Gmdon Crawford Collection, Samford University.

The site McElwain selected for construction was aptly suitable for the furnace with its mountain backdrop available on which to build the tramway to dump the iron ore, coal and limestone into the furnace, the level land at the bottom of the hillside for construction of the workshops, forges, and other necessary structures, and the adjacent Furnace Branch and Shades Creek for providing steam power.

The furnace was blown in by Judge William L. Wilson of Elyton in 1864. "Blowing in" a furnace was a ceremony in which some prominent person or family member is asked to light the fire in the furnace for the first time; probably regarded in the same light as breaking a bottle of champagne on a ship when it is launched. Judge Wilson was also a minister of the Methodist Episcopal Church, a fanner, merchant, tanner and realtor. He was born in Greenville, South Carolina, the son of Allen and Nancy (Cantrell) Wilson. He was elected Probate Judge of Jefferson County in 1862 for a four year term, and declined re-election the next trem.

A description of the furnace as found in Woodward's Alabama Blast Furnaces, states: "The furnace was about 41 feet high and 10 1/2 feet wide in the bosh (at the base). Its stack apparently differed slightly from others of that era in that it was constructed of heavy masonry at the base and of brick, banded with iron ties on the mantle. Although designed for the use

28 A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA

of charcoal for smelting iron ore, it later became the first blast furnace in Alabama using coke for making pig iron successfully. When the furnace first went into production in 1864 it was a cold blast furnace, the blower being a bellows operated by waterwheel power furnished by Furnace Branch. Later steam boilers were installed for hot blast operation and coke was used, increasing the iron yield from seven to ten tons a day.

The pig iron was shipped by oxcart or mule team down the Montevallo-Trussville Road to Brock's Gap at the western end of Shades Mountain to connect with a terminal of the Selma, Rome and Dalton Railroad. Here workers loaded it on a train which carried it to the arsenal in Selma to be fashioned into munitions for the Confederate Army. The Montevallo-Trussville Road went through Mountain Brook along the present-day route of Montevallo Road with some variations and then followed Hollywood Boulevard and Oxmoor Road further west past Shannon. Brock's Gap is located near the Parkwood community on Highway 150.

During this time many people were employed to man the furnace, work the mines, cut, haul, and fire the timber, to care for the many mules and oxen necessary in the daily operations of the furnaces, and to perform all the other jobs connected with the production of pig iron. Most of these workers were hired slaves, and, after the war ended, some of the "owners" sought to locate McElwain and collect the wages due them for services rendered by their slaves.

The fuel was taken from the woods within a six mile radius of the furnace with the timber being cut into cord wood lengths and pits were made in the woods for the purpose of making charcoal. Afterwards four-mule teams or oxen pulled the charcoal to the plant. Six or seven mule teams and at least half a dozen yoke of oxen were kept on hand to do this. Around 30 men were involved in chopping wood and making charcoal.

A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA 29

McElwain chose to build his furnace tucked away in a remote area of Jefferson County where he believed it would be safe from detection and destruction in the event northern troops invaded the valley. However, when Wilson's Raiders eventually passed through Jefferson County in 1865, someone (probably scouts who came in advance of the troops with the express purpose of finding the furnaces) had done excellent ground work, because the location was known. Wilson dispatched his troops on a sweeping raid through the area in April 1865 and both blast furnaces in the county, Red Mountain in Oxmoor and Cahaba Iron Works, were destroyed, as well as Tannehill on the southwestern boundary in Tuscaloosa County. Others outside the county, including Shelby and Bibb Furnaces, were among those leveled in the devastation. All of the wooden structures of these furnaces were burned and everything else that could be broken down was destroyed. There is nothing to indicate a battle actually took place at the

30 A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA

McElwain's furnace. Most of the workers were slaves who undoubtedly welcomed the company of soldiers as their saviors.

According to The Greenville Advocate of April 18, 1867, "the furnace had scarcely ceased its smoldering, after being burnt by the Federal army when McElwain, with perseverance that animates and kindles the spirit of progression," started making plans to get back in operation at the earliest possible moment. As soon as hostilities ceased he went to Cincinnati, Ohio and enlisted assistance from Abel D. Breed of the firm of Crane and Breed to whom he entered a Warranty Deed on all his property in Jefferson County on March 6, 1866. With McElwain now serving as Superintendent of the plant, the furnace went back in operation in 1866. The height of the furnace was increased to 46 feet, and hot blast stoves were installed, as well as a steam blowing engine. This took the place of the less efficient water powered blower.

The Greenville Advocate proclaimed that he fed about three thousand people in 1866, "a large number of whom would have been classed among the indigent, and thrown upon the charities of the people, but for the employment he gave" and encouraged other industries to use him as an example. Three thousand people appears to be an extremely high figure, but in all probability he did provide assistance in one form or another to many needy people at the end of the Civil War. In addition, his commissary provided a more convenient location for the purchase of supplies for people in Shades Valley. Prior to this it had been necessary for them to make the long trip over Red Mountain to Elyton, the closest place of any size, for the necessities of life.

In July 1866 the Cahaba Iron Works paid $10.00 on the first internal Revenue Assessment list in our nation. This tax went into effect in 1865/66 to help reduce the debts incurred by the federal government in the Civil War. McElwain must have suffered a staggering financial loss on the destruction of his furnace, but still placed the value of his property at $20,000 four years later on the 1870 Census.

Ethel Armes in The Story of Coal and Iron in Alabama tells of the "Big Jim" whistle used when the plant went back into operation. It was

A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA 31

said to be one of the biggest and loudest whistles and it was blown in the morning and again in the evening to announce the beginning and ending of the work day. Some years later when Swedish sea captain, Charles Linn, purchased the machinery of the furnace for use in the Linn Iron Works, "Big Jim" then became a pan of Birmingham's history as it continued performing its role.

Like other young people in the county, Ida McElwain was sent to Elyton to receive her early education, where she and other students resided with merchant William L. Wilson, the judge who "blew in" the furnace in 1863.

On the 1870 Census of Jefferson County, O. McElwain, a 60 year old male, born in Massachusetts, resided with the family, and very likely was the father of Wallace McElwain. Also residing with the family was H.D. Merrill, McElwain's cousin as well as his associate in the furnace. They were listed on the Rockville District enumeration. When McElwain started the furnace back in operation a number of families from Blount County moved into Shades Valley to work there. Among these people were Hamp Wade, Green Jones, Blueford Cornelius and a Mr. Blakeley. Other men living in the area who might have been associated with the furnace were P.C. Williams, William Sims [Sims' son, William T. Sims, is buried in the McElwain Cemetery], and Robert Jones, blacksmiths; S. Willson, millwright; S.W. Hollingswsonh, tanner; John Moore, carpenter; and John Perryman, stonemason, might have assisted in the restoration.

In time the outlook for the furnace operations became disappointing for several reasons. Other plants opened up in areas that were competitive; the price of iron fell; and McElwain's health declined. On May 16, 1871 Jefferson County Probate records show that Abel D. Breed and Martin H. Crane of Cincinnati, Ohio, Joseph D. Webster of Chicago, Wallace S. McElwain of Jefferson County and E.G. Barney of Selma, trading under the name of the Cahaba Iron Works, sold to James H. McKee of Philadelphia, James Thomas of Parryville, William R. Thomas and James W. Fuller of Catasauqua, (all from Pennsylvania with McKee, Thomas and Company) all of their property including coal, iron and timber land, the foundry, machine shop, machinery, blacksmith shops, stables, offices and buildings.

32 A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA

James Thomas was nephew of David Thomas, Esq. the great iron master of Pennsylvania. (Ed., James Thomas was the son of Hopkin Thomas -- he was not related to David Thomas.) These men named their operation the Jefferson Iron Company, and named Thomas the General Superintendent of the firm. At the time this company started in operation, knowledgeable men were brought in from other sections of the country to work in the furnace. They secured a Mr. Cartright connected with a firm in Ironton, Ohio, as founder. He brought with him other men trained in the business. Others who came from the Lehigh Valley in Pennsylvania with James Thomas and his family were Asa Beers, George Cook, Thomas Pettit and family, Samuel Davis and family and Robert Stephens. Stephens, experienced in the ore mines of New Jersey, became foreman of the ore mines.

A reporter with The South, a New York newspaper dated April 5, 1873, said: "A train road, one mile and three quarters, connects the mines with the furnace. Here is the only place where we saw iron ore mined, and although Red Mountain at this point seems to be solid ore and the outcrop is more extensive than at many places, still this company finds it profitable to work only certain rich veins, which contain less silicious matter, are softer and more easily reduced in the furnace."

In 1918 Samuel Davis described the living conditions in the vicinity of the furnace in a letter to George Gordon Crawford, President of T.C.I.:

There were quite a few log cabins and a few frame structures called "houses." The mode of living was primitive and in order to make our families more comfortable these "houses" were obliged to undergo reconstruction, the mechanics and material being secured at Elyton, the county seat at that time. Religious services were conducted by Episcopalians, Baptists and Methodists in the little frame schoolhouse on Sabbath day and the education of children during the week was not forgotten. A very interesting incident occurs to me at this time. We were honored by a visit from the Reverend Wilmar, Episcopal Bishop of Alabama, who preached a very instructive and appreciative sermon much to the delight of those who had the pleasure of hearing him ... Our mode of travel to reach Birmingham was on horse-back over the mountain a distance of about seven miles, and unless necessity demanded it our trips were like "angels' visits" few and far between.

A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA 33

In addition to the furnace, other buildings on the property consisted of a two-story frame building 30 ft. by 50 ft., the first floor being used as a machine shop which was equipped with the best known tools manufactured at that time. The second floor of this building served as a pattern and carpenter shop. The foundry and blacksmith shop were built of brick from material supplied on the property and made there. The motive power for the machine shop was steam. The blacksmith shop was equipped for three fires.

Soon the financial panic of 1873 caused the closing of the furnace. H.D. Merrill went to work at the Ishcooda Mines after McElwain sold out, and later operated the Cornwall Furnace for a short time. In 1880 he became foreman at the Alice Furnace and then became purchasing agent for the Elyton Land Company. While under contract with the Sloss Company, Merrill eventually quarried some of the first dolomite used in the Birmingham district.

Boss McElwain (as he was fondly called by his associates) sold the last of his Jefferson County property on June 29, 1874 to A.P. Cochrane of Louisville, Kentucky, and moved to Oxford in Calhoun County, Alabama where he lived until late 1880. Although daughter Alice's obituary indicated he worked for the Selma, Rome and Dalton Railroad, on the 1880 Census McElwain's occupation identified him as agent for the Iron Works. This iron works probably was the Woodstock Iron Company located on a site 300 yards north of the ruins of the old Oxford Furnace which Union troops destroyed during the Civil War. Samuel Noble, with Gen. Daniel Tyler as financial backer, formed the company in 1872 and in later years opened three other plants. Trained workers were hard to find and Noble's brother, James, traveled as far as Europe searching for the right people to man the furnaces. Noble probably rolled out the red carpet for McElwain as men of his training were hard to find locally.

McElwain spent his final years in Chattanooga, Tennessee where he worked as a clerk with W.B. Lowe and W.A.L. Kirk in Lowe's Foundry and Machine Co. This firm manufactured parts for engines, cotton gins, pumps, blast furnace and mining machinery, steam boilers and many other pieces of machinery. Survived by his wife and two daughters, McElwain died in Chattanooga in late 1882 or early 1883 of tuberculosis.

34 A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA

A home still stands in Mountain Brook that was at one time a vital part of the furnace complex, the commissary. The actual date of construction of the home is not certain, but it is believed to be the oldest home left in Mountain Brook, dating back at least to the days of William M. Cummings. Cummings was the original purchaser of the land from the Federal Government on February 7, 1849," which might be a clue to the approximate date of construction. He was married to Malinda Armstrong February 6, 1855 by his neighbor, Willis Eastis. Their home was originally a two room log cabin with a dogtrot. One of these rooms and the dogtrot were tom down many years ago and the house added onto, but the one room survives and is the living mom for Mrs. Edward Beaumont. The exposed white oak logs and a sample of old flooring kept for sentimental and historical value, make this attractive room all the more interesting. Mrs. Beaumont removed the siding from the logs outside of the living room some years ago and today this interesting memento of Mountain Brook's history is revealed for everyone passing by to appreciate and enjoy.

A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA 35

In analyzing the situation that existed in 1863 when the land was purchased, it is logical to assume that the McElwain family moved into the house already on their property. The only other piece of property they owned at that time, the parcel purchased from the Eastis family, may not have had a house on it since the Eastises owned other land in the area. With the cabin within easy walking distance to the location selected for the furnace, it very likely was used as their home until another could be constructed.

36 A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA

Now, nearly all traces of McElwain's furnace in Shades Valley are gone although an occasional reminder can be seen. A trail leads from Stone River Road southwestwardly along Furnace Branch of Shades Creek to a towering stone wall built into the hillside that long ago supported part of the structure of the furnace complex. Protruding from a mound of dirt left when developers changed the stream bed is a rusty beam which may be a part of the tramway, and, from time to time, small bits of metal or pieces of green, blue or lavender slag are washed clear by the rains. But, for the most part, fern, wild flowers and moss now carpet the ground that once bustled with activity, and a feeling of tranquility and remoteness from civilization enters the souls of the people who venture down the path today. Now the site has nearly returned to its original state before civilization intruded the valley.

A HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN BROOK, ALABAMA 37

To reach the site of the Cahaba Iron Works, drive down Old Leeds Road to its intersection with Old Leeds Lane, across the road from the Mountain Brook Club golf course. Drive approximately one mile to Stone River Road and turn left. The City of Mountain Brook has provided parking spaces on the immediate right (east) side of the road, and an historical marker indicates the path that leads to the old furnace site. This site was donated to the Park and Recreation Board of Mountain Brook by the developers of Cherokee Bend in 1960.