Giles Edwards, Alabama’s Leading Proponent of Coke as Furnace Fuel

by Jim Bennett

Newsletter of the Birmingham-Jefferson

Historical Society, April 8, 2010

Giles

Edwards, builder of the first Alabama blast furnace blown in on coke, was a

Welsh immigrant who figured prominently in Birmingham’s rise to the top among

the nation’s great iron and steel centers.

Well

educated on advancements in iron making in Europe, he brought many innovations

to his American experience beginning work in 1842 as a draftsman at the first

iron plant built at Carbondale, Pennsylvania. Edwards later worked in the mills

at Scranton, and superintended the Thomas works at Tamaqua and Catasauqua, also

in Pennsylvania.

Early on

Edwards’ expertise drew the attention of iron mogul David Thomas, considered to

be “the father of the American anthracite iron industry.” Thomas had built the

first successful coal-fired furnace at Catasauqua in 1840. Like Edwards, he was

born in Wales in the County of Glamorgan, almost in

the shadow of the giant ironworks at Dowlais. At one point in the 19th century this place had been the largest

iron producer in the world.

In Thomas’

employment, Edwards’ health began to fail from overwork and after a short stay

at the Novelty Ironworks in New York, the company convinced him for health

reasons he should move south to Chattanooga, Tennessee where the iron industry

was beginning to show promise.

Here the

East Tennessee Iron Manufacturing Company had built the Bluff Furnace on the Tennessee

River near the Walnut Street Bridge in downtown Chattanooga in 1854-56 as a charcoal

furnace. It shut down three years later to be converted to coke, the first

southern iron furnace to use the new fuel source. There is speculation the

furnace was actually leased to a group of northern iron investors including

John Fritz, builder of the furnace and rolling mill at Catasauqua where Edwards

was employed. Investors, possibly some hidden ones, were interested to see if

quality pig iron could be made from coke using Southern coal.

Under Edwards’ direction, along with

James Henderson of New York, the Bluff Furnace was converted into the first

coke-fired furnace in the Southern Appalachian region in 1859 - 1860. It

featured a number of innovations including a cupola-type iron jacket stack 11

feet in diameter and a modified hot blast stove.

This iron jacket

extender, designed to increase production, would later be used at both the Oxmoor and Brierfield Furnaces in

Alabama after the Civil War.

Operations at

the Bluff Furnace came to a stall following political unrest and a worker’s revolt

during the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860. With the experiment deemed a

success, the plant closed and Henderson moved back to New York. Edwards moved

further south to become assistant superintendent of the Shelby Furnace which was being modernized. As federal troops advanced

toward Chattanooga in 1863, the Bluff Furnace plant was dismantled and the

machinery shipped to the new Oxford Iron Furnace under construction near

present day Anniston. A portion of the blast equipment is also thought to have

also made its way to the Shelby Furnace with Edwards.

It was at the

Shelby Rolling Mill in 1864 that armor plate for the ironclad CSS Tennessee was

rolled.

After the war,

Edwards also helped rebuild the Brierfield Rolling

Mill and put the nearby Bibb Furnaces back into operation for Gen. Josiah

Gorgas who had purchased the site as war contraband in June of 1866.

Shortly after,

Edwards moved to the Tannehill Furnace site as land

agent for the Thomas family whose Pioneer Mining and Manufacturing Co. had

bought 2,615 acres in 1868 for its huge iron ore reserves.

En route to Tannehill in 1871, his wife, Salinah,

remarked from the train, “On our way to Tannehill we

passed through Elyton and saw the site of Birmingham.

There were only two section houses for the men starting the railroad—nothing

else. But my husband pointed up the long valley. There lies Birmingham, he said…all

that’s going to be Birmingham some day and he spread his arms out to take in

the entire country.”

Near the Tannehill Furnaces, Edwards moved into the old “Mansion

House”, probably where the Tannehill furnace master

had lived during the war, and explored new ore fields to open for the Thomas company.

“No man before

Giles Edwards,” wrote historian Ethel Armes, “learned

or demonstrated the significant value of the mineral deposits in just this

particular section.”

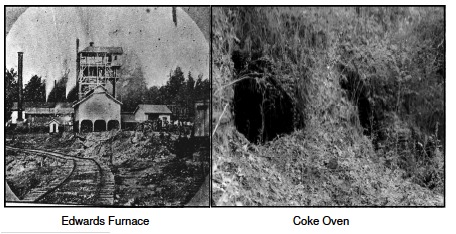

He soon acquired

in the Tannehill area certain valuable properties of

his own where he began building the Edwards Furnace in Woodstock seven miles

distant in 1873, it becoming the first Alabama furnace blown in with coke. The

Alice Furnace in Birmingham was also blown in on coke later the same year.

Coke had been

used experimentally in charcoal furnaces during the war years and Shelby had

used raw coal. In 1864, the first successful coke iron was actually made at the

Irondale Furnace during an experiment sanctioned by the C.S. Nitre Bureau. Although successful, the test did not

persuade Alabama iron makers to abandon charcoal until after the war was over.

Edwards, perhaps

more than most, understood the value of coke as a replacement for charcoal as

fuel in the southern iron industry. Beginning in Wales and later in

Pennsylvania and Tennessee, he knew it made little sense to decimate hundreds

of acres of forest when tons of coal were under their

feet.

At his new

Woodstock furnace, Edwards built a water elevator to bring raw materials to the

top for charging. The blowing engine was the same one used at the old Irondale

plant, the flywheel of which weighed 36 tons and was rated at 150 hp. No doubt,

many spare parts were also picked up at the burnt-out Tannehill

site, just a few hundred yards from his residence.

Brown ore mined

near the site also was shipped to the rebuilt Oxmoor

plant where it was mixed with Red Mountain iron ore. Edwards built an ore

washer and a tramway to the Alabama & Chattanooga Railroad (later the

Alabama Great Southern), a distance of one-fourth mile to expedite delivery.

The Edwards

Furnace, hit with economic downturns and expansions, was remodeled several

times. Shareholders included Henry F. DeBardeleben,

builder of several furnaces in Bessemer. Before closing in 1890, Edwards

Furnace could produce 30,000 tons of pig iron per day.

Edwards and his

family lived a short distance from the furnace and jonquils still bloom each

year at the home site behind what may be the largest oak tree in Bibb County.

His two daughters were married at the family home in a double ceremony in 1899.

Lydia married James W. McQueen, who would later become vice president of Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron Co. and Gertrude married D.

W. Pickens.

Interestingly,

during one of the down times, Edwards is engaged at the Oxmoor

Furnace in 1883 where a recent fire had closed the plant. Here he rebuilds the

facility for the Eureka Company. It was at this site that the famed “Eureka

Experiment” in 1876 proved once and for all that coke made from Alabama coal

could successfully be used in the manufacture of pig iron.

Said DeBardeleben, founder of Bessemer and a former manager of

the Oxmoor Furnace, “Giles Edwards was a conceiver of

big projects. He was one of the first men in the state to see the big

possibilities ahead and to cast his lines and work accordingly. He was well

informed on coke, coal and iron. He was a practical geologist and a scholar,

had one of the best libraries in the state. He was a good draftsman besides, a

first rate one and an excellent citizen, none better.”

Edwards died in

1892 while still living at his Woodstock residence at age 68. He is buried in

Oak Hill Cemetery in Birmingham in the McQueen plot next to his wife who helped

him build the Edwards Furnace. The transition from charcoal to coke in Alabama

was complete.

In March of

1862, noted Welsh iron-master Giles Edwards came to Shelby Iron. Born in

Glamorganshire, South Wales, September 26, 1824, Edwards had, by about 1842, made

his way to Carbondale, Pennsylvania, near the head of the Lackawanna River. There,

he superintended pattern making at the first iron mill in that town. Edwards

later worked with mills at Scranton, and superintended the Thomas works at

Tamaqua, Pa. From Pennsylvania, Edwards moved south to Tennessee, where he supervi sed the rebui lding of the Blufff urnace at Chattanoog a.

Following this reconstruction, Judge John Lapsley

of Selma, a new shareholder at Shelby, requested Edwards to superintend the

reconstruction and expansion of the Shelby works.