Hopkin Thomas and the Beaver Meadow Railroad

Hopkin Arrives at Beaver Meadow

As we have learned in the preceding chapter, Hopkin Thomas was asked by Andrew Eastwick to assist in the delivery to Beaver Meadow of Garrett & Eastwick’s first engines in late October, 1836. So we can surmise that Hopkin returned from the factory to his home and family that fine fall day and addressed his wife, “Dearest, I have been asked by Mr. Eastwick to assist him in the delivery of two of our engines to Beaver Meadow”. Whereupon Catharine would perhaps have responded, “My goodness, Hopkin, where is Beaver Meadow? It sounds as though it is in the wilderness!” “Well, not quite the wilderness, but it is in a mountainous area 100 miles north of here where coal is being mined. It will probably be ten days or so before I return.” “Well Hopkin, do be careful of the wild animals and don’t be so adventuresome that you get lost in the forest. I will ask some of our good friends to help me with the children here in our lovely neighborhood.”

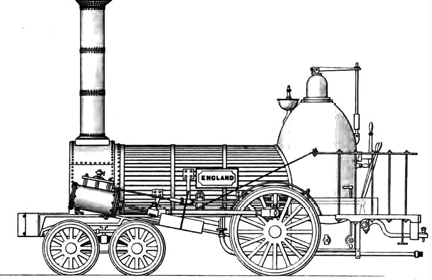

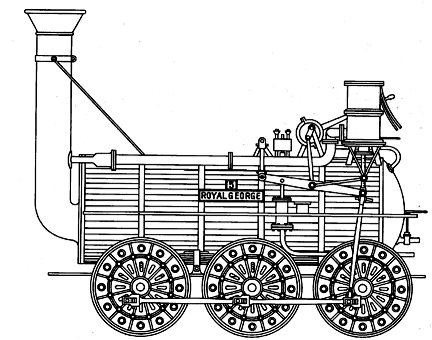

A 4-2-0 locomotive typical of the two engines

delivered to the BMRR by Hopkin Thomas and Andrew Eastwick in October 1836

Upon the success of the engine delivery, Alfred Longshore notes there was a celebration at Wilson’s Hotel in Beaver Meadow, attended by officials, contactors and others, where a basket of champagne was opened. It is likely that at that time, that the officers of the BMRR approached Andrew Eastwick and received permission to offer Hopkin a position with the BMRR. Let us further suppose that Hopkin accepted.

Upon his return to Philadelphia, “The Athens of America”, Hopkin would have addressed Catharine; “Dearest, I have accepted a position with the railroad. We shall move to Beaver Meadow within the month.” After Catharine regained her composure, she probably inquired; “My dear, is there housing there? Is there a school for William? Are there other families with children that can play with Mary, Helen and James?” However Hopkin responded, the Thomas’s were residents of Beaver Meadow by 1837.

The modern (?) railroad depot at Beaver Meadow. What was there when Catharine and Hopkin

Thomas arrived with their family in 1837? A bit of a change from Philadelphia,

I suppose.

Despite the severe economic depression, known as The Panic of 1837, the year 1837 proved to be a time of high activity for the BMRR. The corporate Annual Report for 1837 reported that engine houses, turnouts, pivot tables, water stations, chute screens, crane, etc. were constructed A stationary engine was also erected at the mines, and 86 new coal and lumber cars built, and 40 new mine cars built. The larger engines that were acquired, particularly the Beaver, Nonpareil, and Hercules took on the heavy loads to Parryville and locomotive operations from the mines to the Weatherly planes began. More details are found in that annual report.

The organization responsible for the operations was as follows:

George Jenkins, who joined the company in September,

1836 was Superintendent of all the Company and Works. Jenkins was authorized to

investigate the purchase of locomotives from sources other than Garrett &

Eastwick. By May of 1837 he was referred to as “Cap” Geo. Jenkins and took

charge of all BMRR activities in Northampton County (which apparently included

Carbon County at that time).

Little is known of Jenkins activities in future years.

Aaron H. Van Cleve was Jenkins’

assistant. Van Cleve had intimate knowledge of the BMRR operations. (In later years, Van Cleve was to form a

partnership with Hopkin Thomas which ran all the BMRR operations in Carbon

County.)

Hopkin Thomas was in charge of all shops as Principal

Machinist (aka Master Mechanic or Chief Engineer).

Hopkin’s Technical Activities in the Early Years

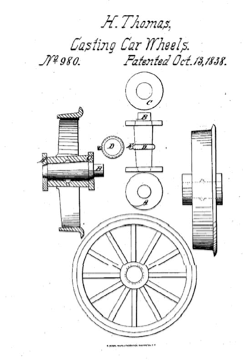

During the years 1837 – 1838 Hopkin had a number of items that needed to be addressed. One was the issue of the need to frequently replace the wheels on the coal cars due to the wear and tear produced by the heavy loads. The following note was posted in the Minutes Book on Jan 9, 1839:

The repairs of engines and cars, will always be a

heavy item of expense. Efforts have been made to reduce this as much as

possible, by improved construction of them, with the means of prompt and

vigilant attention to this branch. Among those improvements, that of chilling

the solid nave of the car wheels. In a new method invented by H. Thomas, with

conical hardened axles, promises to be of great advantage, as also the oil cup

in the pedestals of the axles, by which much waste is avoided in lubricating

their journals.

Hopkin received a patent on the process he employed for improving wheel durability.

There are many references to the use of chilling

(shrink-fitting) steel wearing surfaces on cast-iron wheels. Several histories

pertaining to Hopkin Thomas’ use of this technology imply that he invented

related processes , but no specifics have been found. A brief write-up on this

technology, sometimes referred to as chilled cast-iron wheels

is found in Colburn’s The Locomotive Engine.

Another project undertaken by Hopkin was the improvement in the ability of the locomotives to burn anthracite coal. The Garrett & Eastwick locomotives were designed to burn anthracite (see this note from the LC&N 1838 annual report), but as Alfred Longshore reported,

“We used hemlock wood and frequently had to use water

from the Lehigh when the boilers were nearly empty. When we stopped, the draft

was shut off and the fire died out. Then we had to climb around on the

mountains to gather pine knots for kindling.”

So, Hopkin turned his attention to improving the operation of the locomotives when burning anthracite. In the Minutes Book on Jan 9, 1839, the following passage was recorded:

All the Company's engines burn coal with the greatest

facility; no difficulty occurs in raising and keeping up steam. The apparatus

for improving their draft, was introduced into the United States, by the

Company's machinist, H. Thomas. The whole expense of it is not more than twenty

dollars, including the labour of attaching it, which can be done in one day.

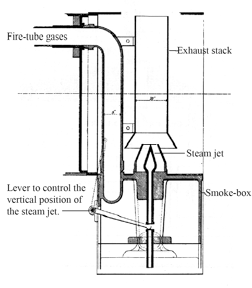

A specific reference to the device used is given by von Gerstner in his review of the Beaver Meadow Railroad:

“The only device used to augment combustion consists

of a vessel mounted on the smoke chest above the cylinders. The steam expelled

from the smoke chest into this device passes through a number of small pipes

and then into the stack. By this simple device, which causes the steam to pass

in a uninterrupted stream through the stack, the draft is very much increased.

In addition, the anthracite burns vigorously, and the production of steam is

promoted to an extraordinary extent.”

There are no illustrations or drawings of the device that Hopkin employed, but it was probably a lever-driven steam jet that could be located at various positions at the entrance to the exhaust stack. The following is a description given by Thomas Evans, a locomotive engineer, who was a longtime friend of Hopkin’s and spoke at a testimonial held at the time of Hopkin’s death:

“As to our first experience at

coal burning, it is impossible to

detail, as we were many times compelled to do things of which we did not know

what would be the result, but having the road to ourselves and determined to succeed,

we finally accomplished it. Many times it would be midnight before we reached

home, although we were due at 6:00p.m. I remained as engineer on the road for

eight months, and at one time kept up my fire for six days without allowing it

to die out, demonstrating that our object had been fully accomplished, keeping

uniform steam and running my trips regularly. You will observe I kept the fire

in all night, in the morning cleaning out well and adding fresh fuel. As it was

before the blower was invented, I would run her empty a few minutes, then

attach to a train ready to commence the day’s work. During our experiments with

coal burning one of the main difficulties we had to encounter was to find out

what draft was needed, and, after months, Hopkin invented a variable exhaust,

by which we could regulate the draft, determining the amount requisite. I

consider the above experiments in coal burning the first knowledge obtained,

the fundamental principles of which are in general use today, but reduced to mathematical

calculations. Ross Winans of Baltimore claims the right of the variable

exhaust, but his patent is dated a few years after we used it.”

Below is a sketch of a variable exhaust system that was employed on the Tyson Ten Wheeler in 1856. Today the device would be referred to as a variable ejector, where a high velocity steam jet induces a greater or lesser flow through the stack depending on the position of the nozzle – which is controlled by a lever. See White for more details. Colburn also includes a section on this technology.

Variable Exhaust System

As an aside, it is interesting to note both Evans’ and White’s opinion of Ross Winans, a noted locomotive designer. There is a definite sense that Winans would steal other people’s ideas, patent them, and charge licensing fees or sue others who employed similar devices.

Anthracite as a Locomotive Fuel

As noted in the previous chapter, the Garrett & Eastwick engines delivered to the B. M. R. R. were designed with the intent of using anthracite coal. Those engines made the initial run from Parryville to Black Creek using wood in the summer of 1836. By December, 1836 it was determined that the operation using anthracite would begin. Subsequently wood was employed only for kindling when the engines were fired at the start of the day. Numerous problems associated with the burning of anthracite ensued; these were the issues that Hopkin Thomas and crew addressed and which are well documented. The bottom line was that all these issues were successfully addressed at the B. M. R, R. Following are references to articles that document these activities.

Continued improvements were made over the years by various locomotive designers when it came to burning anthracite in their locomotives. The difficulty of achieving satisfactory results is apparent by the fact that it took over 30 years for some railroads to achieving success. See Warner’s article on The Development of the Anthracite-Burning Locomotive. John White, in his History Of The American Locomotive attributes the early success of the Beaver Meadow and of Ario Pardee’s Hazleton Railroad, both of which totally rejected the use of wood, to the relative simplicity of their operations compared to a passenger-oriented railroad. Perhaps so, but the use of the variable exhaust addressed the issue of controlling the fire while passengers boarded, as well as other part-load operations and the issue of keeping the fire lit during times of suspended operations.

The difficulties that some railroad operations had with burning anthracite was the subject of numerous articles published in the technical journals of the time – such as The Journal of the Franklin Institute and The American Railroad Journal. In 1847, Walter R. Johnson, Professor of Mechanics and Natural Philosophy in the Franklin Institute, Philadelphia, a well-respected technologist of the day, published an article in the Journal of the Franklin Institute in which he pursued the issue of why the Beaver Meadow and the Hazleton R. R. had such great success with anthracite while other roads had stumbled. He states that one factor was the need for steady, smooth combustion and that was addressed by Hopkin Thomas while at Eastwick & Harrison. Burning out of the grate bars was also addressed at the B.M.R.R. by modifying/eliminating the ash pan. This was related to Johnson by A. H. Van Cleve, obviously based on work that Hopkin and his staff had performed. Further he mentions the technique used at B.M.R.R. for joining the boiler tubes to the boiler drum so that erosion due to ash does not cause premature failure. All in all, the article conveys how much detailed effort Hopkin and company put into the anthracite usage efforts.

In 1849, George W. Whistler published an extensive report in The Journal of the Franklin Institute where the cost of operation of anthracite-fired locomotives was compared to that of wood-burning locomotives. The data collected was largely that from the operations of the Reading Railroad which operated coal-burning locomotives built by Ross Winans. The Reading was simultaneously was operating wood burners. This is a very detailed report which describes many of the maintenance and operations issues which, significantly, Hopkin had addressed at during the prior decade at the Beaver Meadow R. R. The report is well-worth reading, as it lays out the issues that prevented major railroads, who did not have a Hopkin Thomas as master mechanic, from utilizing anthracite coal.

The maintenance issue which was most troublesome on the Winans engines was the erosion of the copper sheets which lined the inside of the firebox. The obvious solution was to use a more rugged material – a material such as iron which could resist the erosive action of the coal and ash particles. Whistler blames the failure to use such materials on the iron-masters who, in his opinion, were unable to produce iron sheets in the size and quality required for locomotive use. Other maintenance issues cited were melting of grate bars, the increased issue of leakage at joints, the wear and destruction to the ends of tubes by caulking, &c., and the accumulation and igniting of fine coal in the smoke box. (All of these issues were assuredly addressed at the BMRR, in fact, Whistler comments that these issues were not significant on the BMRR and Hazleton roads.).

The operations issues which had not been fully addressed in the Reading operations were the use of the variable exhaust and the efficient use of the cut-off. The cut-off was a valving mechanism which cut off the delivery of the steam to the cylinder so that work was performed by the expansive power of the steam when the loads were not heavy as during acceleration and grade climbing. If the cut-off was not employed by the engineer, the steam consumption and therefore fuel consumption increased significantly. In his work, Whistler does refer to the operations of the Beaver Meadow R. R., but does not get into the fact that these issues were successfully addressed. Rather he dismisses the success of the BMRR based on the short runs of that road compared to the typical run on the Reading R. R.

Ario Pardee, the head of the Hazleton Railroad, which operated partly on the BMRR tracks, in apparent exasperation, sent a note to the Franklin Institute in 1854, 18 years after the Hazleton and the BMRR had begun anthracite operations, stating that some of the issues that were quoted as limiting the use of anthracite as “absurd”.

Finally, some 50 years after the initial use of anthracite, the noted historian William Henry Egle published several letters in his Historical Column in the Harrisburg Telegraph which shed light on another aspect of the use of anthracite – the political aspect. Apparently in the late 1840’s the Pennsylvania Senate set up a commission having the objective of prohibiting the use any fuel in locomotives except “mineral coal”. Letters submitted by the B. M. R. R. and Garrett & Eastwick present the perspective of the successful users of anthracite and their view of why others did not achieve success. Of particular interest to this publication is that S.D. Ingham, president of the B. M. R. R. cites having the services of Hopkin Thomas, “a very skilled machinist” was key to attaining success. Ingham also cites the variable draft exhaust (a Hopkin Thomas invention) as a useful device in coal burners. Egle’s letters were reproduced in The Historical Record, a Wyoming Valley history publication available here.

The Nonpariel

The

most noted of Hopkin’s activities in his early years

at the BMRR was the construction of the 6-coupled-wheel

locomotive, Nonpareil, in 1838. Citations

of this work appeared in many of the records of

the day. There seems to be some controversy whether

the engine was an 0-6-0 configuration or a 4-6-0,

but the majority opinion is that it was an 0-6-0.

Unfortunately, no sketches of the engine

have survived. Specific information on the engine

design is recorded in the Journal of the

Canal Commissioners, in

a letter received in May 1839. That

information, compiled by Martin Coryell, “Del.

Div. Penn Canal” indicates that it was an 0-4-0

configuration, had 44–in. drivers, 12-in cylinders,

was designed to burn anthracite, and used an exhaust

equipped with an ejector. The engine weighed 28,800

lbs. and cost $8,575. A description of how the 6

drivers were suspended and the dimensions of the

connecting rods are included. The engine went into

service in September, 1838. Methods of addressing

the durability issues associated with the hot anthracite

fire are noted.

Coryell provides a description of the performance of the locomotive as it carried out its assignment of transporting coal cars from the Beaver Meadow planes to Parryville.

The only other very sketchy information on the engine was published by von Gerstner which referried to the locomotive which “was built in the company's own shops.” “The latter has 6 coupled wheels 44 inches in diameter, 13-inch cylinders, and an 18-inch cylinder stroke. it weighs 26,300 lbs.”

Edith Duncan Field’s biography of Hopkin Thomas contains this description of the building of the Nonpareil – the source of the information is not specified:

Hopkin Thomas undertook to construct a six wheel connected engine at Beaver Meadows with only meager facilities available. The locomotive which he called the "Nonpareil" was built in shops consisting of sheds and stables, the machinery, driven by horsepower, consisted of two lathes, one of which was equipped with a foot gear to be used when the horse was in the stable. There also was a workbench with eight vices, a smith shop with two fires and a pattern shop. The President and Directors of the Company, though dubious of success, were present to witness the Nonpareil's first run, which proved most satisfactory. One Director stating "she moved off gracefully and made her round trip in due time." At the festival to mark the occasion Hopkin Thomas was loudly acclaimed for his feat, which was considered to be the first six wheel connected locomotive to have operated successfully.

The first 0-6-0 engine built in the world -- in England -- was the “Royal George”, built in 1827 by Timothy Hackworth for the Stockton and Darlington Railroad. Hackworth also built the “The Sanspareil”, perhaps the effort that inspired Hopkin to name his engine “The Nonpareil”.

![]()

![]() The

Royal George

The

Royal George

![]()

(The Sanspariel was a smaller engine, an 0-4-0, which was specifically designed for the Rainhill Trials.) Hackworth was also an expert on locomotive exhaust systems. I suspect that Hopkin was well acquainted with Hackworth’s accomplishments.

The reason for building the Nonpareil was that it was apparent to the officials at the BMRR that more powerful locomotives were needed. The Nonpareil and the Beaver, a 4-4-0, were rated at 26 HP versus the 18 HP of the earlier engines in the BMRR roster. In January, 1839, the following note appeared in the BMRR Minutes Book:

“The Company have now five locomotive engines. Three

of them have one pair of driving wheels. One of them (the Beaver) has two pair;

and one (the Nonpareil.) built by H. Thomas at the Company's shops, has three

pair of drivers. The last is of great adhesive power, and more than double the

traction of the three former engines. One of the light engines might now be

sold; and if another of them was replaced by an engine similar to the

Nonpareil, it would greatly increase the Company's means of transportation, and

improve its economy.”

Also:

“The efforts of the Board have been earnestly directed

to improvements in the economy of the various branches of their operations. A

new locomotive engine with six driving wheels, has been built at the Company's

shops, of great power, and better adapted to drawing heavy loads on undulating

and curved roads, than any heretofore used by the Company. The success of this

engine, aided by the eight-wheeled engine used last year, furnish an enlarged

means of transportation, sufficient for a considerable increase of business.”

Other Master Mechanic Activities

As Hopkin’s accomplishments as Master Mechanic became more apparent to the officials of the BMRR, he was called upon to perform additional activities. From January 1839 through May the Minutes Book indicate that he was summoned to Philadelphia to examine an engine on the Columbia RR that was being offered for sale; that he come to Philadelphia to meet with the locomotive manufactures (Baldwin, Eastwick & Harrison, Norris) to view “large locomotives” regarding the purchase of same; that he perform the same duty with respect to a stationary engine (probably for use in the mines). In May, 1839 Hopkin was awarded a salary increase.

Another activity that took place early in the summer of 1839 was the erection of workshops and other buildings in Black Creek (now Weatherly). Reasons cited for this activity included the fact that water-power was available there to run the machinery and that the need to move the locomotives up the planes between Weatherly and Beaver Meadow for servicing would be avoided. According to J. Koehler’s history, the use of water power was a costly failure, and steam power was re-instituted. Eventually, the shops at Beaver Meadow were abandoned. There is no information that suggests that the Hopkin Thomas family moved its residence from Beaver Meadows to Black Creek.

Current Google map showing the locations of Beaver

Meadows and Weatherly. Click to enlarge.

The BMRR shops at Weatherly – date unknown. See

the J.

Koehler history for a map of the complex.

This period of progress was ended in August of 1839 when the company acknowledged that the sagging price of coal was going to require a cut-back in the company’s operations. This is covered in the following section.

Return to the Table of

Contents

About

The Hopkin Thomas Project

Rev.

November 2011