The

Development of the Anthracite-Burning Locomotive

By Paul T. Warner

Railroad &

Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin, Vol. 52 pp 11 – 28.

Ed. Illustrations added by J. McVey

During

the latter part of the eighteenth century, the pioneers living in certain

sections of eastern Pennsylvania became much interested in peculiar mineral

known as "stone coal" or "black stone". As early as 1768 it

was known that it had combustible properties; but owing to the difficulty in

igniting it, the abundant supply of wood fuel available, and the poor

transportation facilities of that time, its use spread slowly. Records indicate

that it was being used for blacksmithing in 1769, and that deposits were located

near Mauch Chunk in 1791. In 1803 a load of stone coal was taken to

Philadelphia, and attempts were made to burn it in the boiler of a steam engine

at the water works; but as the fire was extinguished in consequence, the coal

was broken up and scattered over the sidewalks in place of gravel.

Stone

coal--now known as anthracite, or hard coal--was first placed in the market in

1807, when a certain Abijah Smith loaded 50 tons of it in an "ark" at

Plymouth, near Wilkes‑Barre, and floated it down the Susquehanna to

Columbia, Lancaster County, where he tried to sell it; but there were no

buyers. In the following year, one Jesse Fell made the experiment of burning

stone coal in the fire place in his home, and reported that "it made a

clearer and better fire, at less expense, than burning wood in the common

way."

Anthracite

was first mined by the use of powder in 1818, and thereafter its production

rapidly increased. In that year the Lehigh Navigation Company was organized,

and the coal was soon being regularly floated down river to Philadelphia in

unwieldy boxes called "arks", which were steered by long oars or

sweeps. As it was difficult to get the arks back, they were demolished after

being unloaded, the lumber was sold and the iron‑work returned overland to

Mauch Chunk, a distance of 80 miles. By the time the first railroads were in

operation the value of hard coal as fuel was fully recognized, and one of

Pennsylvania's greatest industries had become firmly established.

Anthracite is the densest, hardest and most

lustrous of all coals, and its combustible content consists almost entirely of

carbon. It burns with very little flame, and with practically no smoke. In

contrast, a true bituminous coal contains a relatively large amount of so‑called

volatile matter which, on the application of heat, is driven off in the form of

a gas. The principal constituents of this gas are hydrogen and carbon, and if

the temperature is not sufficiently high, and the air supply is inadequate, the

carbon deposits as soot, which forms the principal coloring matter in smoke. In

any event the volatile matter burns, not on the grate, but in the space above it. For this

reason anthracite is a slower burning fuel than bituminous coal, but the

heating values of the two are practically equal. Hence to produce a given

amount of steam in a given time we must burn as many pounds of anthracite as of

bituminous, but as the former burns more slowly, a far larger grate must be

provided on which to consume it. The main problem with which the early

designers of hard coal burning locomotives had to contend was that of providing

sufficient grate area, and the story of the development of the hard coal burner

deals chiefly with the struggle to solve this problem.

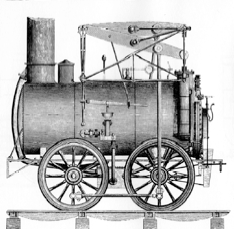

The

first locomotive used in this country was the Stourbridge Lion, imported from England;

and records state that when it was experimentally fired up at New York in June,

1829, Lackawaxen hard coal was used as fuel. It should also be noted that the

first railroad to operate commercially in America--the Baltimore and

Ohio--burned anthracite in its earliest locomotives. The Tom Thumb, built by Peter Cooper

of New York, which made its first successful trip at Baltimore on August 28,

1830, was a hard coal burner. History records that the boiler of this little

machine was of the vertical multi‑tubular type, about 20 inches in

diameter and five or six feet high. Artificial draft was created by a fan

driven by a belt passing around a wooden drum attached to one of the road

wheels, and a pulley on the fan shaft. It was the slipping of this belt that

caused the first locomotive "steam failure" in this country, on that

memorable day when the Tom Thumb was racing a gray horse, attached to another

car on a parallel track.

The Stourbridge Lion The

Tom Thumb

Ross

Winans, in a report made to P. E. Thomas, President of the Company, estimated

that the Tom Thumb,

while running, developed an average of 1.43 horsepower.

The

success of the Tom Thumb convinced the management that it would be advisable to

operate the road by steam power, and on January 4, 1831, the Company issued a

proposal for the construction of locomotives, which was the first of the kind

to be made in the United States. It was agreed that the sum of $4000.00 would

he paid for the most approved engine, and $3500.00 for the next best. Among the

stipulations included in the agreement were the following:

"The engine must burn coke or coal, and

must consume its own smoke."

"The pressure of the steam not to exceed

100 pounds to the square inch; and as a less pressure will be preferred, the

company in deciding on the advantages of the several engines will take into

consideration their relative degrees of pressure. The company will be at

liberty to put the boiler, fire tubes, cylinder, etc., to the test of a

pressure of water not exceeding three times the pressure of the steam intended

to be worked, without being answerable for any damage the machine may receive

in consequence of such test."

"There must be two safety valves, one of

which must be completely out of reach or control of the engine man, and neither

of which must be fastened down while the engine is working."

"There must be a mercurial gauge affixed to

the machine with an index rod showing the steam pressure above 50 pounds per

square inch, and constructed to blow out at 120 pounds."

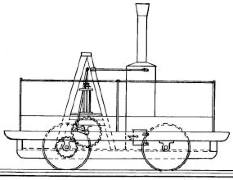

Several

locomotives were built in answer to this proposal, but only one --the York -- proved at all

satisfactory. This locomotive was built by Messrs. Davis and Gartner, of York,

Pennsylvania. It was capable of hauling 15 tons at a speed of 15 miles an hour

on level track, and of running at a maximum speed of 30 miles an hour. The

cylinders were vertical, as was also the boiler, which had an internal,

horizontal water table nicknamed a "cheese", for the purpose of

increasing the heating surface. This "cheese" gave trouble by filling

up with mud and burning out. Anthracite was used as fuel, and artificial draft

was furnished by a fan.

The York

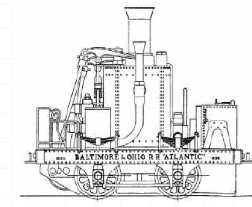

The

York was followed by a group of vertical boiler locomotives which were known as

either "Grasshoppers" or "Crabs", according to the design

of their machinery. The Grasshoppers had vertical cylinders, with vibrating

beams which were fulcrumed on top of the boiler; while the Crabs (which were a

creation of Ross Winans) had horizontal cylinders. The boilers of all these

locomotives were of the multitubular type, burning anthracite and fitted with

blowers operated by exhaust steam. The Crabs also had feed‑water heaters,

through which the exhaust steam passed before it was discharged into the

atmosphere.

In

the Seventh Annual Report of the Company, issued in 1833, George Gillingham,

Superintendent of Machinery, referred to the Grasshopper Atlantic as having run 13,280

miles, burning 190 tons of coal at $8.00 per ton. This represented an average

consumption of 32 pounds per mile.

The Atlantic

These

vertical boiler curiosities exerted but little influence on the development of

the American locomotive, but because of their unusual design, and the fact that

they successfully burned anthracite, they are deserving of brief mention.

We

now turn to the State of Pennsylvania, where there was under construction a

railroad which was destined to play a leading part in the hauling of anthracite

and the development of the hard‑coal burning locomotive. This was the

Philadelphia and Reading, which was built chiefly for the purpose of

transporting coal from the mines in the anthracite region to tidewater on the

Delaware River. The line between Reading and Philadelphia was completed in

1839, and the extension to Pottsville was opened in 1842. For practically the

entire distance the line had a river grade, either level or slightly

descending, from the mines to tidewater. The grades were favorable to the

loaded movement, and presented no serious obstacle to the hauling of empties on

the return trip.

The

first locomotives used by the Reading burned wood, but in 1839 the road placed

an order with Messrs. Eastwick and Harrison, of Philadelphia, for a high‑powered

freight engine to burn anthracite. This engine, the Gowan and Marx, was one of the most

famous locomotives ever built. At the time of its construction, Eastwick and

Harrison had acquired an excellent reputation as locomotive builders. This was

largely due to the invention, by Joseph Harrison, Jr., of the equalizing beam,

patented April 24, 1838, which made it possible to build coupled locomotives

that were sufficiently flexible to operate safely on the poorly surfaced tracks

of the period. Eastwick and Harrison had built a number of hard‑coal

burning locomotives which were operating with a fair degree of success, notably

on the Beaver Meadow Railroad.

The

Gowan and Marx

was of the 4‑4‑0 type, designed to weigh 11 tons, with 9 tons on

the drivers. This unusual weight distribution was obtained by placing the

firebox over the rear driving axle and using a short boiler barrel and wheel

base, thus throwing the center of gravity as far to the rear as possible. The

firebox was of the Bury, or hay‑stack pattern, with a grate area probably

approximating 12 square feet, which was considered exceptionally large. As in

most of the Eastwick and Harrison locomotives, the cylinders were placed at a

steep angle, and the pistons were outside‑connected to the rear pair of

drivers. The exhaust steam was discharged into two copper chests, or draft

boxes, and escaped up the stack through a large number of openings instead of

through a single nozzle. The object sought was to create a more even draft on

the fire. In May, 1839, the Committee on Science and the Arts of The Franklin

Institute had investigated the performance of an Eastwick and Harrison hard‑coal

burner. Their report, referring to the draft boxes, stated that "with the

aid of this contrivance, the anthracite fire is kept in a state of intense

activity, and generates an abundance of steam, without the annoyance and danger

arising from the smoke and sparks of a wood fire".

The Gowan & Marx

The

locomotive mentioned in this report was operating at Philadelphia, but

unfortunately no reference is made to the name of the engine or to the road for

which it was built.

The

grates of the locomotive just referred to consisted of grooved wrought iron bars,

which were protected from the action of the fire by a coating of clay placed

within the grooves. The grates of the Gowan and Marx were doubtless

constructed in the same way. The latter locomotive was also the first one to be

equipped with a blower for stimulating the fire.

On February 20, 1830, the Gowan and Marx startled the railroad

world by hauling a train of 104 loaded four‑wheel ears weighing 423 tons

from Reading to Philadelphia at an average speed of 9.82 miles an hour.

Including the weight of the engine and tender, the total load equalled forty

times the weight of the locomotive. A report of this remarkable run was issued

by G. A. Nicolls. Superintendent of Transportation of the Railroad Company,

under date of February 24, 1840. This report stated that the locomotive

consumed 5600 pounds of red ash anthracite, while evaporating 2774 gallons of

water. This represented an actual evaporation of 4.13 pounds of water per pound

of fuel. It was also stated that "the steam ranged from 80 pounds to 130 pounds

per square inch, to which latter pressure the safety valve was screwed down.''

With 130 pounds pressure, the locomotive must have been exceedingly

''slippery". Mr. Nicolls described the engine as having cylinders

measuring 12 2/3 by 16 inches, and driving wheels 40 inches in diameter; and he

gave the total weight as 24,660 pounds, with 18,260 pounds on drivers.

The

Gowan and Marx

was a success, and twelve locomotives of similar design were ordered in 1842

from the Locks and Canals Company of Lowell, Massachusetts, and were delivered

in 1843; but it was evident that, for reliable service, increased grate area

was needed for burning such a refractory fuel as anthracite. Mr. Nicolls

tackled the problem, and the result was an amazing creation which was built at

the Reading Shops in 1846 and was appropriately named Novelty. The details were

worked out by Lewis Kirk, who at that time was Master Mechanic. The engine and

boiler of this curiosity were mounted on separate vehicles, the idea being that

they could not both he placed on the same set of wheels and made of sufficient

capacity. The Novelty. although a courageous venture, proved a complete failure

and exerted no influence on locomotive design.

The

next step to produce a successful hard‑coal burner was taken by Ross

Winans, of Baltimore, ‑who was proving a prolific designer of railroad

motive power. In 1847 he built four locomotives of the 0‑8‑0 type

for the Reading. The firebox was of the Bury, or hay‑stack pattern, but

in order to provide sufficient grate area it had a flat‑sided, rearward

extension, rectangular in cross‑section. This construction resulted in a

heavy overhang, throwing an excessive amount of weight on the rear wheels. To

obviate this, Winans placed a pair of pony wheels under the foot plate and the

locomotives were then accepted. They had a grate area of 17.66 square feet, and

burned anthracite more successfully than any locomotives previously tried. In

spite of the progress made, however, the year 1850 found the great majority of

the Reading's locomotives still burning wood.

The

next steps in the development of the hard‑coal burner were taken by James

Miliholland who, in the late forties, was placed in charge of the Mechanical

Department of the Reading. He was an inventive genius and an excellent

mechanical engineer; and while he made mistakes, he turned out locomotives

which had no superiors at the time of their construction. In a report of

Superintendent Nicolls dated December 1, 1851, it is stated that

"satisfactory results have been obtained from the application of an

improved method of burning anthracite coal in locomotives, invented by James

Millholland, Master Machinist, by which the quantity of coal consumed and the

intensity of the fire are alike diminished.

''The

successful experience of this improvement for several months, in five engines,

has established its value, and proved that anthracite coal is, at present

prices of wood, the most economical fuel we can use in engines adapted to its

combustion.

Quoting

further from the same report, we read

''The

'Allegheny' engine has been completely rebuilt, in place of an engine of the

same name, whose Boiler had proved defective from age and inferior iron. It has

been built with Mr. Millholland's improvement, and has, so far, worked remarkably

well."

This

"improvement", was doubtless the one mentioned by Angus Sinclair on

Page 289 of his book "Development of the Locomotive Engine", where he

says, "The furnace was kept within the frame line until it reached the

back of the hind drivers, when it was spread, reaching about five inches beyond

the rail on each side." Dr. Sinclair states that the first engine so

rebuilt was the Baldwin locomotive Warrior, but the Annual Reports of the

Philadelphia and Reading Railroad Company indicate that the Warrior was not

rebuilt until 1858. However that may be, it is interesting to note that in the Railway

Mechanical Engineer

of May, 1916, there was illustrated and briefly described a 4‑6‑2

type compound locomotive on the Paris‑Orleans Railway of France, which

had a firebox similar in plan to that attributed to Mihiholland by Sinclair.

On February 7, 1852,

Millholland took out a patent for a locomotive boiler designed to burn hard

coal. This boiler, in modified form, was applied to the freight locomotives of

the Pawnee class, built at the

Reading shops during that year. These locomotives were of the 2‑6‑0

type, but were not true Moguls, because the leading wheels were placed back of

the cylinders arid were held rigidly in the main frames. The boiler had an

overhanging firebox with a short combustion chamber, and there was also an

intermediate combustion chamber, thus necessitating the use of two groups of

tubes. In design and workmanship these locomotives represented the best

practice of their day, but they were poor steamers. Millholland, following the

ideas of the period, provided his coal‑burners with an assortment of

mixing chambers and ingenious gadgets which, while they may have been

theoretically desirable, worked poorly in practice.

We

must now leave the Reading for a time, and turn our attention to the Delaware,

Lackawanna and Western Railroad which, although it was rapidly becoming

important as an anthracite carrier, was using wood as locomotive fuel. Like the

Erie, this road was originally constructed with a track gauge of six feet. The

first hard coal burner built for the Lackawanna was ordered in October 1853,

from Danforth. Cooke and Company, of Paterson, New Jersey, and was

appropriately named Anthracite. This engine was completed in May, 1851. The

design, for which Watts Cooke, subsequently Master Mechanic of the Lackawanna,

was largely responsible, closely followed Miliholland's Pawnee class. The wheel

arrangement was the same, and the boiler was very similar in construction. The Anthracite, however, in its

original form, gave no end of trouble. The locomotive would not operate safely

on the crooked tracks of the Lackawanna. until the rigid leading wheels were

taken out and a four‑wheeled swiveling truck substituted for them. The

locomotive was also a poor steamer. A very intense draft was found necessary,

and this pulled the coal through the rear tubes into the intermediate

combustion chamber, which rapidly filled up, choking the tubes and causing

steam failures. It was necessary to remove the intermediate combustion chamber

before the locomotive could be made to steam satisfactorily.

The

second hard coal burner used on the Lackawanna was the Carbon, built by the ingenious

Ross Winans of Baltimore, and placed on the road in October, 1854. This was a

genuine Winans "Camel," and was representative of one of the most

unusual types of locomotives ever used in this country. The wheel arrangement

was 0‑8‑0, and the boiler had a long overhanging firebox. The crown

and roof sheets sloped toward the rear at. a sharp angle, and there was

practically no steam space above the crown. The grates were of cast iron,

arranged so that each bar could be shaken independently of the others. In

addition to the firedoors at the rear, there were two ''chutes'' on top,

through which coal could be dumped on the grates. A huge dome, almost as large

in diameter as the boiler itself, was placed just hack of the smokebox. The

connection of this dome with the barrel was a serious source of weakness, and

the Camels were subject to rather frequent explosions.

Five

additional locomotives of this type, but of somewhat larger dimensions, were

placed on the Lackawanna in 1856. When operated at slow speed they were fairly

successful, but they soon failed at speeds exceeding ten miles an hour. All

were scrapped in 1859, as they were considered unsafe to operate.

The

next Lackawanna engine demanding our attention was the Lehigh, built by the New

Jersey Locomotive Works of Paterson, and completed in February. 1855. This

engine was originally designed by Zerah Colburn. who was one of the most noted

mechanical engineers of the period. It was of the 0‑6‑0 type, with

an overhanging firebox of 7' 6" in width. Colburn's intention was to use a

firebox six feet long, but he left the New Jersey Locomotive Works before the Lehigh was completed, and the

builders reduced the length to 4' 6. The locomotive proved a poor steamer, and

the firebox was subsequently lengthened to six feet, as proposed by Colburn.

Five

additional locomotives of the Lehigh type were ordered from the New Jersey

Locomotive Works in 1856, and all of them were partially rebuilt with longer

fireboxes about two years later.

The

first really successful anthracite burners used on the Lackawanna were the Investigator and Decision, which were turned out

of the shops of Danforth, Cooke and Company in April, 1857. They were of the 4‑6‑0

type for freight service, and had wide overhanging fireboxes placed back of the

rear drivers.

The

Philadelphia and Reading, in the meantime, was having some interesting

experiences with Winans Camels. Eleven of these remarkable locomotives were in

use on the road in 1852; fifteen more were purchased in 1854, at a cost of

$150,000, and in the following year 17 more were bought for $165,000, making a

total of 43. As originally built, the Camels had no water space in the back of

the firebox; and side sheets, especially those of iron, failed frequently.

Copper side sheets proved more reliable, but there was no marked improvement

until Miliholland rebuilt the fireboxes with a back water space. This change

also permitted him to put in water‑tube grates, which proved more durable

than cast iron grates. With the latter, it was found preferable to use an

inferior grade of anthracite, as the resulting accumulation of ash and cinder

protected the cast iron bars from the intense heat of the fire. With high grade

fuel of low ash content, the bars burned out rapidly, but this difficulty was

avoided with the water‑tube grate.

It

is difficult for us today to appreciate the problems which had to be solved by

the men who designed these early hard‑coal burners. They realized the

need for ample grate area, but had many trials and tribulations in trying to

obtain it. A low center of gravity was considered essential, and hence the

boiler was carried at the lowest possible elevation. A firebox with sufficient

grate area for burning wood could be placed between the frames and axles, but

such a location provided insufficient space for an anthracite‑burning

firebox. Apparently the only alternative was to use an overhanging firebox, and

this resulted in a locomotive that was liable to rock and prove unsteady on the

track when run at more than moderate speed. The frames were usually stopped in

front of the firebox, and hence it was difficult, to provide a satisfactory

connection between the locomotive and tender. In many cases the tender drawbar

was attached to the ash pan. which in turn was braced to the frames at its

forward end. This was, to say the least, a most unmechanical arrangement, but

it apparently served the purpose fairly well.

The

problem was finally solved, on both the Lackawanna and the Reading, by raising

the boiler and p1acin the firebox above the rear driving axle. Miliholland

placed his grates above the frames, thus obtaining an area of 241/2 square feet

in a firebox seven feet in length, He developed locomotives of the 4‑4‑0

type for passenger service, and the 4-6‑0 for freight, that had no

superiors at the time of their construction. In the report of Superintendent Nicolls

dated November 30, 1859 we read: 'The two new coal‑burning passenger

engines Hiawatha

and Minnehaha.

have been completed, and in use for some months. In economy of fuel and

repairs, and general efficiency, these locomotives have proved superior to any

yet used, and are believed to furnish an excellent model for others which may

be hereafter required for similar service". This proved to be a fact; for

the Reading designs of the late fifties continued to be built, with

comparatively little variation, until the advent of the Wootten boiler in 1877.

Miiholland's locomotives had boilers with radial‑stay fireboxes, water‑tube

grates, and two steam domes. An inspection of the drawings of the Hiawatha. shows that such

features as sloping throats and back heads were not unknown at that time, and

reveals a boiler which was quite as "crooked" in appearance as any

built during recent years.

Under

date of December 13, 1859, Millholland addressed a most interesting report,

covering the subject of anthracite as locomotive fuel, to R. D. Cullen, then

President of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad Company. The report stated

that there were only four wood-burning locomotives left on the railroad, and

that the coal burners were far easier to manage than the wood burners, as they

had to be fired only every 40 minutes. With full trains of 100 loaded cars

carrying five tons per car east‑bound, and 110 empties westbound, the

coal consumption for the round trip of 190 miles was nine tons.

As

compared to a soft‑coal burner of the same nominal capacity, the hard‑coal

burner of the sixties and seventies was somewhat heavier, with a larger

percentage of total weight resting on the driving wheels. This was particularly

true of the 4‑4‑0 and 4‑6‑0 types, which were built in

large numbers; and was due to the long firebox of the hard‑coal burner,

which extended over the back driving axle, throwing the center of gravity

toward the rear. The additional weight on drivers was an advantage in the case

of locomotives inclined to be "slippery". The grates of the hard‑coal

burners were composed of water tubes about two inches in diameter, and in a

firebox of the usual width two or three "pull‑out" bars were

inserted. These rested in thimbles placed in the water legs, or sometimes, at

the front of the grate, on suitable bearing castings; and they could be drawn

out when dumping the fire. The usual ratio of grate area to heating surface was

about 1 to 40, as compared with 1 to 60 in a soft‑coal burner.

Stacks

of various kinds were used on the hard‑coal burners -- straight stacks,

diamond stacks, sun‑flower stacks, and even Laird balloon stacks, were

tried at various times and in accordance with the ideas of master mechanics.

The straight stack finally prevailed, and became practically universal before

the final discarding of the diamond stack on soft‑coal burners.

Variable

exhaust nozzles were almost universally used on anthracite burning locomotives

sixty or more years ago. Probably the most common type had an internal plug,

which could be raised or lowered within the nozzle, thus varying the size of

the annular opening through which the steam escaped. The Bolton nozzle

consisted of flexible steel plates, surrounded by a cast iron ring, which could

be raised or lowered, thus allowing the plates to spring apart or be drawn

together, and varying the size of the opening. Ross Winans, in 1847, patented

an exhaust which was used, at least to some extent, in his Camel engines. The

opening in the nozzle was rectangular in cross section, and its width could be

varied by changing the distance between two vertical plates. The device was

operated through gearing, by a handle placed in the cab. According to Herbert

T. Walker, this type of exhaust nozzle was applied to the Lackawanna Camels.

The operating handle in the cab was derisively known as the "coffee

mill." The device would frequently clog with cinders and become

inoperative, the result being a surprising amount of railroad profanity. It was

therefore customary to set it at a point which gave generally satisfactory

results, and let it stay there.

The

year 1866 is of special interest, because it marked the introduction of the so‑called

Consolidation type of locomotive. The original "Consolidation' -- the

first 2‑8‑0 type with separate tender -- was built by the Baldwin

Locomotive Works to specifications prepared by Alexander Mitchell, Master

Mechanic of the Lehigh and Mahanoy Railroad. At the time of its construction,

the Lehigh and Mahanoy was being consolidated with the Lehigh Valley, and the

locomotive was named "Consolidation" in honor of the event. The name

stuck to the type. Although Matthias W. Baldwin predicted the failure of Mr.

Mitchell's new engine, it proved a great success; and the Lehigh Valley took a

leading part in the development of the Consolidation type for heavy coal and

freight traffic. In order to obtain sufficient grate area for burning

anthracite, these locomotives had fireboxes ten feet long. The big

Consolidation type of the seventies had 20x24‑inch cylinders and driving

wheels 50 inches in diameter, and weighed about 100,000 pounds in working

order. The preference of the Lehigh Valley for these large locomotives was due

to the fact that there were heavy grades on its main line, up which coal had to

be hauled while moving east‑bound from the mines. The Reading, as has

been mentioned, was more favorably situated in this respect, having a

descending river grade east‑bound over practically its entire main line.

It was handling coal traffic with Millholland Ten‑wheeled (4‑6‑0

type) engines. These were popularly known as "gun boats", and they

weighed 25 to 30 per cent less than the Consolidation type locomotives.

In

a report of John P. Laird, Master of Machinery of the Pennsylvania Railroad,

dated December 31, 1862, it was stated that experiments were being made with a

passenger locomotive designed to burn anthracite, and that the relative merits

of hard and soft coal as locomotive fuel were being thoroughly tested. In the

report of the following year, it was stated that the hard‑coal burner had

not proved successful, and that it had been, rebuilt to use bituminous coal and

was "doing very well". This was probably the Pennsylvania's first,

but by no means only experience in the use of anthracite.

In

June, 1871, the Pennsylvania leased the lines of the United New Jersey Canal

and Railroad Company; and for many years thereafter it owned and operated a

large number of hard‑coal burners. The first "standard" design

of hard‑coal burner was Class C Anthracite (subsequently Class D4) which

was turned out in 1873. This was a 4‑4‑0 type engine which, apart

from its boiler, was practically a duplicate of Class C (or D3), a soft‑coal

burner which was then the most successful all‑around passenger and fast

freight engine on the railroad. As compared with Class C, the grate area of the

hard‑coal burner was increased .63 percent, and the total heating

surface, 7 percent. This latter increase was the result of using a larger

number of tubes of reduced diameter. The total weight of the locomotive was

slightly increased, while the weight on drivers was raised about ten per cent.

In

1876 John E. Wootten, then General Manager of the Philadelphia and Reading,

became interested in the problem of using refuse anthracite as fuel. In a

statement dated December 21, 1876, published in the Annual Report of the

Company for that year, he says: "An important economy, introduced during

the year, has been the utilization of coal dirt, from the waste heaps at the

mines, for generating steam in stationary boilers at the shops and at stations

on the line. A locomotive using this fuel is also doing efficient service.

Nearly seven‑thousand tons of this waste material has thus been

profitably consumed during the year".

Mr.

Wootten was seriously tackling the problem of burning refuse coal in

locomotives; and in January, 1877, the first locomotive with a boiler specially

designed to burn this fuel was turned out of the Reading Shops. This engine,

No. 408, was of the 4‑6‑0 type for freight service, with 18x24‑inch

cylinders and driving wheels 54 inches in diameter. Application was made for a

patent covering the new type of boiler, and this patent‑No. 192,725‑was

granted July 3, 1877. It had one claim, reading as follows :

A locomotive engine in

which a firebox wider than, and a grate as wide as or wider than, the distance

between the driving wheels, and arranged above the same, are combined with a

bridge M, extending across the said firebox, and with the auxiliary combustion

chamber, all substantially as set forth.

This

patent was followed by another, No. 254,581, dated March 7, 1882, which

illustrated a boiler similar to that shown in connection with the first patent.

The principal claim of the second patent was that the entire firebox should be above the bottom line of the

waist or barrel of the boiler.

The

design of the Wootten boiler showed considerable ingenuity. In order to burn

refuse coal successfully it was necessary to carry a thin fire and work it with

a light draft, and this necessitated a grate area far larger than could be

obtained in a firebox placed between the wheels. At the same time there was a

strong prejudice against raising the boiler, the fear being that such a plan

would render the locomotive unstable and liable to upset when rounding curves.

Mr. Wootten therefore, while extending his firebox beyond the wheels and

raising it above them, used an extremely shallow throat, in combination with a

combustion chamber which extended forward into the boiler barrel. There was a

raised water space, surmounted by a fire‑brick wall, across the rear of

the combustion chamber, and this permitted the watertube grate to be placed

entirely above the bottom line of the boiler barrel. Owing to the width of the

firebox, two fire‑doors were provided. The crown sheet of the firebox was

horizontal, but the roof sheet sloped toward the rear at a fairly steep angle,

providing very little steam space at the back. The mud ring, or water space

frame, was made of flanged plates shaped like an. inverted U, and carefully

fitted and riveted to the inside and outside firebox shells. The firebox was

supported on the frames by means of vertical expansion links at the front and

back. A short smokebox was used, with a variable exhaust nozzle and a register

in the front door for the admission of air.

Two

other patented devices of Mr. Wootten's were applied to engine 408. One was a

grate composed of water tubes between which were placed cast iron bars having

narrow air openings. The other was a feed‑water heater, consisting of a

long cylindrical drum traversed by tubes through which part of the exhaust

steam passed. A pump, worked from a return crank attached to the rear crank pin

on the right hand side, forced water into the drum, where it absorbed heat from

the exhaust steam. The condensate was drained through a pipe at the back end of

the drum.

Engine

408 proved successful, and was followed by others of similar design. One of

them, No. 412, was sent to Europe and exhibited at the Paris Exposition of

1878. It was subsequently tried on the Northern Railway of France and also on

several Italian roads, where it burned low grade fuel with marked success.

In

the first Wootten boiler locomotives constructed, including engine 412, the cab

was apparently placed over the firebox. On account of restricted clearance

limits on the Northern Railway of France it was necessary, before placing the

locomotive in service on that line, to move the cab ahead of the firebox so

that it could be lowered. This was probably the first of a long series of

locomotives subsequently nicknamed "Camel‑backs" or

"Mother Hubbards".

While

the records indicate that Wootten boiler locomotives for passenger service were

built at Reading as early as 1878, the first of such locomotives to be fully

illustrated and described in the technical press was apparently engine 411,

which was turned out of the Reading Shops in May, 1880. A similar engine, No.

506, followed in June. The writer has distinct recollections of both these

locomotives, and he has ridden behind them on the Bethlehem Branch. They were

of the 4‑4‑0 type, and were the heaviest passenger locomotives in

the country at the time of their construction; and they set the pace for high‑speed

motive power, not only on the Reading, but also on other railroads. Their

cylinders had the unusual dimensions of 21x22 inches; the drivers had a

diameter of 68 inches, and the steam pressure was 140 pounds. The boiler was of

the full‑fledged Wootten type, with a grate area of 76 square feet.

Engines

411 and 506 were placed in fast passenger service on the New York line,

operating between Philadelphia and Bound Brook. It was customary to change

engines at the latter point, using the locomotives of the Central Railroad of

New Jersey between Bound Brook and Jersey City. The Reading locomotives made

two round trips, aggregating 240 miles, per day. According to the late J.

Snowden Bell the fastest schedule allowed 64 minutes for the 54.9 miles between

Wayne Junction and Bound Brook, including one stop and three slow‑downs.

At full power 53 pounds of anthracite were consumed per minute, and 55 gallons

of water were evaporated. In this severe service, each engine crew consisted of

three men, one of whom served as "furnace‑door opener";

"an operation' '‑according to Mr. Wootten‑' 'which facilitates

rapid firing". In regular service a speed of 72 miles an hour was

maintained for a distance of eight miles; and on one occasion a special train

of 15 cars was hauled from Wayne Junction to Bound Brook in 76 minutes.

The

first Baldwin‑built engines to have Wootten boilers were heavy freight

haulers of the Consolidation (2‑8‑0) type, constructed for the

Reading in 1880. They were fitted with Mr. Wootten's patent feedwater heater,

but curiously enough in this case the water was forced into the heater, not by

a pump, but by an injector. In service these locomotives proved so satisfactory

that they were soon followed by others of similar design. The General Manager's

report dated December 31, 1881, stated that the cost of fuel per 100 ton‑miles

for the Ten-wheeled engines using prepared coal was 5‑6/10 cents, while

for the Consolidation using waste coal it was only 0‑6/10 cents. This

represented a saving in the cost of fuel per annum, for each Consolidation type

locomotive, of about $2,500.00. During the year 1883, 171 locomotives using

waste anthracite, reduced the fuel cost by $378,000.00 In addition to this, the

firebox sheets lasted considerably longer in the Wootten boilers than in those

of the conventional type, due to the fact that it was not necessary to force

the fire so hard.

The

refuse anthracite, as received from the mines, usually had mixed with it from

18 to 20 per cent of slate and other impurities. When the Wootten boiler was

first introduced, an attempt was made to burn this fuel without washing it; but

this necessitated cleaning fires so frequently that it was found desirable to

remove the impurities before placing the fuel on the tenders. In fast passenger

service, to insure greater cleanliness and free steaming, it was customary to

burn lump coal; but it was not necessary to "size" it specially, as

was the case with the narrow fireboxes, because the Wootten boilers burned any

size from stove to steamboat.

In

spite of the success of Mr. Wootten's new boiler, the majority of the roads in

the anthracite region resisted its introduction. This was doubtless due, at

least in a measure, to the fact that it was a patented device. The Lehigh

Valley, in 1880, purchased two Wootten Consolidation type locomotives from the

Baldwin Locomotive Works, but adhered to the long narrow firebox for passenger

locomotives. This road was building the majority of its locomotives in its own

shops, and each Master Mechanic was supposed to design motive power best suited

to the requirements of his particular division. Locomotives were built at South

Easton, Hazleton, Weatherly, Delano, Wilkes‑Barre and Sayre; there were

Kinsey engines, Campbell engines, Clark engines, Hofecker engines, Mitchell

engines, anybody and everybody's engines. Apart from the fact that all burned

hard coal, there was no attempt at standardization; the result, according to

the late Angus Sinclair, being "the accumulation of an assortment of

patterns such as no other railroad company ever possessed".

Lehigh

Valley engine 382, the William L. Conyngham, built at Wilkes‑Barre

in 1882, was a fine example of a passenger lump burner She was a particularly

handsome 4‑4‑0 type, with 19x24‑inch cylinders, driving

wheels 68-1/2 inches in diameter, and a grate 10-1/2 feet in length having an

area of 36.8 square feet. This engine, in its leading features and dimensions,

was representative of the general class of passenger power used on the other

principal hard coal roads, such as the Central of New Jersey and the

Lackawanna.

The

Pennsylvania, in 1881, introduced a new series of hard‑coal burning

locomotives, represented by Classes K and A anthracite, which were respectively

used in fast and local passenger service on the New York Division. These

locomotives were of the 4‑4‑0 type, and were designed under the

supervision of the late Theodore N. Ely, who was then Superintendent of Motive

Power. Class K (subsequently D6) had 18x24‑inch cylinders, and was

notable for the size of its driving wheels, which were 78 inches in diameter.

Class A anthracite (subsequently D7) had 17x24‑inch cylinders and 68‑inch

drivers. The boilers of the two classes were closely similar, with fireboxes

ten feet long placed above the frames, and a grate area of 34.7 square feet. As

far as the design of the details was concerned, these locomotives represented

the most advanced practice of their day. They were handsome in appearance, and

there was a refinement in their outline, and an absence of gaudy paint and

brass work, that contrasted strongly with much of the power in service at the

time. A heavier design, with larger cylinders and boiler, designated as Class P

(subsequently D11a) was built in 1883 and for several years thereafter.

In

fast passenger service on the New York Division, the Class K and Class P

locomotives burned hard coal during the summer time and soft coal during the

winter.

It

is interesting to note that in 1883 the Baldwin Locomotive Works built, for the

Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, three narrow gauge 4‑4‑0 type locomotives

designed to burn Colorado anthracite. These little engines, with 12x18‑inch

cylinders and driving wheels 45 inches in diameter, had long narrow fireboxes,

with grates composed of water tubes and pull‑out bars. They were tried in

passenger service, but as hard‑coal burners they were failures, as they

could not be made to steam.

The

Wootten boiler, as originally designed and built, had certain features which

were destined to give trouble. Due to the sloping roof sheet and the large area

of crown sheet with its fiat surface, there were frequent staybolt breakages.

The flanged mud ring proved a source of weakness, as did the raised water space

at the back of the combustion chamber, where seams were prone to leak. The

Baldwin Locomotive Works gave valuable assistance in improving the design of

the boiler and eliminating its weak points. The roof sheet was made horizontal,

the crown sheet was arched all the way around except at the sides, and a solid

mud ring of forged iron was substituted for the plate design. The arrangement

of the throat was changed so that the raised water space in, the combustion

chamber could be eliminated, while retaining the water‑tube grates and

fire‑brick wall.

The

boiler, as thus improved, was applied to a group of 4‑4‑0 type

engines built in 1889 and 1890, at which time Levi B. Paxson was Superintendent

of Motive Power and Rolling Equipment of the Reading. Mr. Paxson did

progressive work in developing the Wootten boiler, and also improving valve

gear design by providing a freer exhaust and reducing back pressure. The 4‑4‑0

type locomotives referred to had the same size cylinders and driving wheels as

the old 411 class, but the boilers were larger and the steam pressure was

raised from 140 to 160 pounds. These locomotives proved a great success,

demonstrating their ability, on special occasions, to maintain an average speed

of 60 an hour between Camden and Atlantic City and doing very creditable work

on the New York run also.

In

the meantime there was being developed the so‑called modified type of

Wootten boiler, which had a wide firebox without a combustion chamber. Mr. S.

M. Vauclain, of the Baldwin Locomotive Works, gives chief credit to Alexander

Mitchell of the Lehigh Valley, for perfecting this design. However that may be,

it is interesting to note that a boiler of the modified Wootten type was

applied to Baldwin engine No. 5000, an experimental single‑driver engine

built in March, 1880, for high speed service on the Bound Brook line. This

locomotive had the 4‑2‑2 wheel arrangement, with a wide firebox

placed back of the drivers and over the trailing wheels. The firebox was

radially stayed, and had a straight tube sheet and water-tube grate. The

locomotive proved capable of maintaining high speed, but it made only a few trips

on the Reading; and it was subsequently sold to Lovett Eames, who took it to

England to exploit his patented vacuum brake.

The

locomotive just mentioned had a deep firebox, with ample space between the

grate and the bottom row of tubes; but when the modified Wootten design was

first placed above the drivers, the throat was so shallow that trouble was

experienced. The fuel choked up the bottom tubes, and cold air passing through

the grate frequently caused them to leak. This difficulty was overcome by placing

the tube sheet five or six inches ahead of the throat, thus causing the

equivalent of a very short combustion chamber or, as it was called, a D‑head.

This kept the tubes out of the fire, and gave any cold air an opportunity to

heat up before it struck the tube sheet. There was nothing new about the D‑head,

as it had been used for many years in narrow fireboxes. It was simply applying

an old device to overcome a new difficulty.

Mr.

Wootten took out several patents covering wide fireboxes with straight tube

sheets. One of these described a curved brick wall placed on the grates and

abutting against the tube sheet, thus keeping the fuel out of the tubes and

forming a small combustion chamber. In another arrangement, the lower tubes

were kept so far above the bottom of the boiler shell that the fuel could not

get into them. This plan sacrificed a considerable number of tubes, with a

corresponding reduction in heating surface. Mr. Wootten also took out a patent,

jointly with J. Snowden Bell, under date of April 19, 1887, covering a wide

firebox which was divided into two chambers by means of a longitudinal water‑leg.

The chambers united, at the front of the firebox, in a common combustion

chamber which was separated from the grates by walls of firebrick. If this plan

of firebox was ever actually used, the writer is not aware of it.

In

addition to the railroads which have been thus far mentioned, many other lines

in the east were using anthracite to a greater or less extent. Among these were

the Central Railroad of New Jersey, the Erie, the New York, Susquehanna and

Western, the New York, Ontario and Western,, the Delaware and Hudson, the West

Shore, the Long Island, the Erie and Wyoming Valley, and various smaller roads.

The New York Central and Hudson River burned anthracite in suburban service out

of New York City, and the switching in the Grand Central station was done with

hard‑coal burners.

The

West Shore had in service two classes of 4‑4‑0 type locomotives

which were alike except for the fireboxes, one class burning bituminous coal

and the other anthracite. Both classes had 18x24‑inch cylinders and

driving wheels 68 inches in diameter, and carried a steam pressure of 14,0

pounds. Four of these locomotives, one of them a hard‑coal burner,

participated in a run made on July 9, 1885, with a three‑car special

train, from East Buffalo to Weehawken. The average speed while running was

nearly 50 miles an hour, and the performance, at that time, was regarded as

quite an achievement. The locomotives were built by the Rogers Locomotive

Works, and the run is described in great detail in the 1886 edition of the

Rogers catalog.

The

success of the Wootten boiler, in both its original and modified forms, led to

the re‑boilering of many hard‑coal burning locomotives originally

having narrow fireboxes. If the drawings of these boilers could be studied,

some interesting designs would be revealed. The Lehigh Valley, in a number of

cases, built wide fireboxes with the Belpaire system of staying, the inside and

outside firebox sheets being parallel to each other so that the stay-bolts were

normal to both. This system, of construction was subsequently used by the

Pennsylvania Railroad in the boilers of its first Atlantic type locomotives,

which will be described shortly.

Brief

reference should here be made to a number of three‑cylinder hard‑coal

burners, built for the Erie and Wyoming Valley Railroad. In 1880 Mr. John B.

Smith, Superintendent of the Pennsylvania Coal Company, built four small

switchers of the 0‑4‑0 type, each of which had three cylinders.

While records of their dimensions and service are not available, they were

apparently satisfactory; for in 1892 Mr. Smith constructed, at the works of the

Dunmore Iron and Steel Company, a wide firebox, three‑cylinder passenger locomotive

of the 4‑4‑0 type, for the Erie and Wyoming Valley. This was

followed, in 1894, by three freight locomotives of the Mogul (2‑6‑0)

type, built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works. In this design there were three

17x24‑inch cylinders set on an incline, with all the pistons connected to

the second pair of driving wheels, and cranks placed 120 degrees apart. These

locomotives had Wootten boilers carrying a steam pressure of 150 pounds, and

developed a tractive force of 23,300 pounds. In proportion to their weight they

demonstrated remarkable hauling capacity, especially on grades.

As

far as the writer is aware, the only other three‑cylinder hard‑coal

burners on record are those built by the Philadelphia and Reading at the

Reading Shops during the years 1909‑1912. Three of these were of the

Atlantic type, while the fourth was a ten‑wheeler. They all did fine

work, but were subsequently rebuilt with two cylinders.

During

the nineties the locomotive weight record was broken by three groups of

anthracite burners, all built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works. First were the

four 0‑10‑0 type tank engines, specially designed to operate

through the St. Clair Tunnel near Detroit. Each locomotive was required to haul

a train weighing 760 tons up the two per cent grades at the tunnel entrances.

The locomotives had side tanks and a centrally located cab, the coal bunker

being at the rear end. The boiler had a long narrow firebox, with a water‑tube

grate having an area of 38.7 square feet. The St. Clair Tunnel was electrified

in 1908.

Late

in 1891 the weight record was again broken, when five Decapod (2‑10‑0)

type locomotives were built for the Erie. These were intended for pushing

service on the Susquehanna Hill, where the grade is 60 feet to the mile. They

had Wootten boilers with combustion chambers, and rocking grates having an area of 89.5 square feet. There

was a centrally‑located cab and also a commodious shelter for the fireman

at the rear end. Vauclain compound cylinders were applied.

The

third record‑breaker was built for the Lehigh Valley Railroad in 1898,

and was intended for service on the Mountain Cut‑off near Wilkes‑Barre.

Like the Erie locomotives, these Lehigh Valley engines had Vauclain compound

cylinders; but the boilers were of the modified Wootten type with a D‑head

firebox. The grate area was 90 square feet. On the Mountain Cut‑off each

locomotive was rated to handle 1000, tons up a grade of 60 feet to the mile at

a speed of 17 miles an hour.

The

Brooks Locomotive Works, in 1899, built heavy anthracite burners of the Twelve‑wheeled

(4‑8‑0) type for the Central Railroad of New Jersey and also for

the Lackawanna. Apart from minor details these two groups were practically

alike. They had single‑expansion cylinders, with piston valves, boilers

of the modified Wootten type and centrally located cabs.

Excluding

some switching engines, the only hard‑coal burners built by the

Pennsylvania up to 1899 were passenger locomotives of the 4‑4‑0

type. The final development of this type was seen in the D16 group, which was

introduced in 1895 and was built for several years thereafter. These engines

had grates ten feet long, with, an area of 33.2 square feet, and were built

with two sizes of driving wheels.68 and 80 inches in diameter. Since 1889 the

Pennsylvania had been using Belpaire boilers on its standard passenger

locomotives, and Class D16 had a boiler of that type. These locomotives were

used in both hard coal and soft coals territory, and for some years worked the

bulk of the fast passenger traffic east of Pittsburgh. They have now nearly all

disappeared, but they were undoubtedly among the most satisfactory locomotives

ever used on the road.

The

first locomotives of the Atlantic (4‑4‑2) type to have Wootten

boilers were built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works in April, 1896, to the order

of the Philadelphia and Reading for service on the Atlantic City Railroad. The

running time between Camden and Atlantic City, 551/2 miles, was being steadily

reduced, and the new engines were designed to handle a train of eight cars on

this run in 60 minutes, or one of six cars in 50 minutes. It was estimated that

a maximum of 1400, indicated horsepower would be required to do this work. The

locomotives as built, had Vauclain compound cylinders and driving wheels 841/4

inches in diameter. The steam pressure carried was 200 pounds, and the boiler

had a combustion chamber, the grate area being 76 square feet and the total

heating surface 1835 square feet. Under test the locomotives developed 1450

indicated horsepower at a speed of 70 miles an hour.

The

success of these locomotives led the Railroad Company, in1897, to put on one

train which was scheduled to make the run in one hour fiat, including the time

required to ferry the passengers from Philadelphia to Camden‑an operation

for which the time‑table allowed eight minutes, but which invariably

required more time. The train, hauled by engine 1027, ran every week‑day

during the months of July ‑and August. It was composed of either five or

six cars, as required, and was never once late at Atlantic City; the fastest

time for the run being 46-1/2 minutes, equivalent to an average speed, start to

stop, of 71.6 miles an hour. The average time consumed was 48 minutes,

equivalent to a speed of 69 miles an hour. Considering both speed and

punctuality, it was an astonishing record.

The

Pennsylvania watched the proceedings, and in 1898 put on a sixty‑minute

train which was run over, the old Camden and Atlantic Railroad. The track

mileage was 58.3 as against 55-1/2 by the Reading, but the ferry at the

Philadelphia end was considerably shorter, so that there was little to choose

as far as running speeds were concerned. The Pennsylvania hauled their train

with a 4‑4‑0 type locomotive of Class D16a which, although among

the finest representatives of the type ever built, were handicapped through

having to burn anthracite in a narrow firebox. Comparing the locomotives used

by the two roads, it may be noted that while the Pennsylvania engine had the larger

total heating surface and weight on drivers it had less than half the grate

area of the Reading engine. The compound cylinders of the latter may have

helped a trifle, for the high‑wheeled Vauclain compounds, when properly

maintained, were fast runners; but the big grate was the feature that did the

business. The Pennsylvania probably would have done better with bituminous

coal, but they had to meet the Reading slogan of 'no smoke, no cinders"‑-the

latter item open to doubt.

In

1899 the Pennsylvania met the situation by bringing out their first wide

firebox Atlantic Type locomotives Class El. There were three of these engines

-- numbers 698, 700 and 820 -- and it is safe to say that, at the time of their

construction, they represented the most careful designing and the finest

workmanship that could be found in this country. They met the 60‑minute

schedule without difficulty and demonstrated their ability to easily maintain

an average speed of 75 miles an hour from Hammonton to Drawbridge, a distance

of 27.4 miles, with trains weighing 300 tons behind the tender.

In

view of the many interesting details of Class El, including the cylinders, the

valve gear and machinery, the frames and running gear, and the boiler, a

complete description of this class would require a lengthy article. Our

interest centers chiefly in the boiler, which may be described as a Belpaire

Wootten. The firebox had a combustion chamber with a brick wall built across

the back of it, in accordance with Mr. Wootten 's design, but following

Pennsylvania practice the Belpaire System of staying was employed. The crown

and roof sheets were flat and horizontal, and the water spaces were of liberal

width throughout. The grates were of the rocking type arranged to shake in four

sections, and particular attention was given to the arrangement of the ash‑pan

and smoke‑box. All these features contributed to the success of the

locomotives.

The

Pennsylvania's Class El may be considered as representing the high‑water

mark in the development of the hard‑coal burning locomotive. It had many

fine contemporaries -- such as the Black Diamond engines on the Lehigh Valley,

the Baldwin and the Brooks Atlantics built for the Central Railroad of New

Jersey, which were used in the New York‑Philadelphia service, and the

highly efficient eight‑wheelers and ten‑wheelers of the Lackawanna

-- but the rest of the story can by told in a few words. The Pennsylvania built

no more hard‑coal burners; on their subsequent Atlantics they narrowed

the firebox sufficiently to place the cab at the rear, and used bituminous coal

as fuel.

Subsequent

to the opening of the present century the railroads in the anthracite region

continued, on new power, to use boilers of the Wootten and modified Wootten

types, enlarging the fireboxes until grate areas reached, and in some cases

even exceeded 100 square feet. Such boilers were used on locomotives of many

types, notably the Pacific (4‑6‑2) for heavy passenger service, and

the Consolidation (2‑8‑0) and Mikado (2‑8‑2) for

freight. Watertube grates gave way‑ to those of the rocking pattern, or

to a combination of widely spaced water‑tubes and rocking bars. As boiler

dimensions increased it became impossible, to provide room for the enginemen in

a centrally‑located cab, and the cab was moved to the rear. While these

changes were taking place, the increasing cost of anthracite, and the

difficulty in generating sufficient steam in very large locomotives when using

that fuel alone, resulted in the general use of a mixture of buckwheat

anthracite and bituminous coal. The necessity of using mechanical stoker on the

largest locomotives encouraged the use of a high percentage of bituminous, as

it has not been found practicable, in locomotive service, to burn straight

anthracite with a stoker.

Many

of the most recent locomotives now operating in the anthracite region were

designed to burn straight bituminous coal; and even when mixtures are burned,

Phoebe Snow is finding it necessary to keep off the railroads -- unless she

rides in air‑conditioned trains. Large numbers, of former hard‑coal

burning locomotives with boilers of both the full Wootten and modified, Wootten

types, are now operating on straight bituminous coal. In the interest of

economy it has doubtless become necessary to do this; but the resulting effect

on the atmosphere in such regions as the Schuylkill and Lehigh Valleys, and

other districts which might be named, is sad to see.

The

Wootten boiler, although originally designed to burn refuse anthracite, pointed

the way toward the development of the high‑power soft‑coal burning

boiler as we have it today. To meet the demand for motive power of high

capacity, the soft‑coal burning boiler gradually developed into one

having the most prominent characteristics of the Wootten type ‑a wide

firebox with an extremely large grate, and a combustion chamber extending

forward into the boiler barrel. Therefore, although anthracite has practically

passed out of the picture as a locomotive fuel, its use, in past years, was a

factor of first importance in the development of the present‑day super‑power

locomotive.

Return

to Hopkin Thomas / Beaver Meadow Railroad Page

About The Hopkin Thomas Project

Rev. May 2010