Some Comments on a Letter of 1833 from

the Baltimore & Ohio R. R. to the Stockton & Darlington Ry. in England

BY G. A. PETCH

Railway & Locomotive

Historical Society, Vol. 90, pp 157-161

The

cause of these few notes is a letter of 1833 recently unearthed in the book

used by an ironmaster of Darlington, England, to record copies of his outgoing

mail. The letter was written by Evan Thomas in Baltimore to Edward Pease, the

founder of the first English public railway, the Stockton and Darlington.

Edward Pease lent the letter to a young acquaintance of his, Alfred Kitching,

who had just extended the family iron business to supply the railway. The

letter reveals what was considered of sufficient news value in 1833 on the

Baltimore and Ohio Railway to write a letter about it to send across the

Atlantic. Similarly, the fact that Kitching made a copy of it shows it was of

outstanding interest to him, an English railway engineer, for this was a

practice which he followed on no other occasion in his letter books.

Baltimore

11

Mo. 26, 1833

Respected

Friend,

Edward

Pease.

The

bearer of this letter is my nephew John Ellicot who will I expect visit your

very interesting Railroad Establishment, in the course of his Tour in England.

As

he is well informed relative to the present state of the acts in this country

he may perhaps be able to impart some useful hints in matters of that nature.

We

have been steadily progressing in improving our railroad system especially the

machinery connected with—as it regards Steam Power our advance has been

very great. Our engines now building are to convey 120 tons 15 miles the hour

on a level road. The boilers are vertical, 4 feet diameter with 400 tubes or

pipes 15 inches in length. The fuel is anthracite coal which neither gives out

smoke nor particles of inflammable matter, when properly ignited it imparts an

intense heat. This is effected by applying the waste steam to a fan which

throws a powerful current of air into the furnace. The Engines now in operation

generate steam so rapidly that at least 1/3 is thrown off. The tubes or pipes

last 3 times as long as those in StephensonÕs Engines. We have also made great

improvements in those parts of wagons and carriages subject to friction by

which they not only last much longer, but a prodigious saving of oil is

effected as well as much time in oiling.

We

have likewise improved the form of our wheel and have recently rendered it much

stronger by introducing a wrought iron ring in it, so that even should a wheel

become fractured by a severe concussion it still continues serviceable being

held together by the iron ring. I am informed by the superintendent of

Machinery on the Baltimore and Ohio Rail road that not one wheel has yet given

way in which the wrought iron ring has been inserted. In the Locomotive Engine

wheels two wrought iron rings are inserted and such is the firmness with which

they are held together that it has been found impossible to break them asunder

with sledge hammers until a sufficient portion of the cast metal is detached to

permit the ring being cut by an instrument. John Ellicot will take with him a

segment of one of the waggon wheels, showing the wrought iron ring, the ring

should be warmed a little before it is put into the mould. All our wheels are

chilled on the outer periphery, the insertion of the iron rod in the thickest

part of the wheel makes the case hardening more perfect at that point. (?)

From

thy affect. friend

EVAN

THOMAS

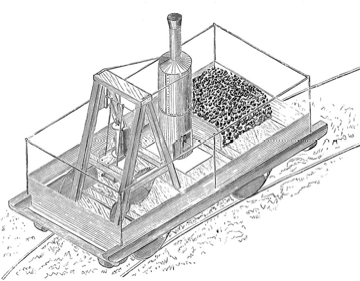

Sketch

of the Tom Thumb.

Both

the Darlington men concerned were Quakers, whilst the use of the phrase

"Respected Friend" as a mode of address and the scrupulous use of the

merely mathematical "llth month" instead of the heathen word

"November" show that the American writer belonged to the same

religious group. The Quakers have been most commonly known for their

"Meetings" in which all sat in silence until divinely inspired to

speak. Another less known but important aspect of their Society was the

thoroughness of its organization on an ascending scale of Meetings from local

to national, the whole structure bound together by ministers who traveled from

Meeting to Meeting inside the country and also abroad as "the spirit moved

them" and "way was opened. " Edward Pease's published diaries show

that, despite the difficulties and distance of connections with America, he was

very well acquainted with the interests and problems of American Quakers. Hence

this familiar association, religious in its foundation even though commercial

in its present uses. There were, of course, other and purely commercial

relationships between the railwaymen of the two countries. Stephenson's firm

and others were exporting some locomotives to America and John Ellicot was not

the only American of the time to make a tour of inspection of the English

railways. We are apt to think of Anglo-American economic cooperation as a

post-1939 novelty. Here that idea is proved wrong by over 100 years.

The

various technical points in the letter would be of interest to the Darlington

men, partly because they were tackling the same problems themselves, partly

because of their peculiar position in English railway engineering. The

Darlington railway, which was then eight years old, owed a great deal to George

Stephenson whose son's multi-tubular boilers are referred to in the letter.

But, in addition, its locomotive superintendent was Timothy Hackworth,

Stephenson's great rival in engineering, a man who developed his engines on

somewhat different lines from Stephenson and who, perhaps unjustly, did not

achieve the same position as Stephenson either in his own day or in history.

Examples of both the Stephenson and Hackworth engines were on the Darlington

line. Their respective merits are still debated in England and if John Ellicot

saw them and commented on them it would be instructive to hear the skilled

opinion of a neutral observer.

The

stated performance of the Baltimore engine is certainly impressive as compared

with accounts of the Darlington engines of the period. Some few facts may point

the comparison. In 1829 Hackworth's engine the Royal George (built 1827)

"took 48-1/4 tons of goods up and down a portion of the line having a

gradient of 1 in 528, a total distance of 5,000 yards, at the rate of 11-2/10

miles per hour, steam was blowing off when the experiment was concluded."

In 1833 mixed goods and passenger trains of unspecified weights were traveling

at 12 to 14 miles per hour, whilst the railway's "mineral" engines of

this period (i.e. engines hauling coal) have been credited with the following

performance over gently rolling country.

Nos.

of Gross

Load Load

(Empty Average

wagons

Down

Wagons)

up Speed

tons

tons

miles

"Majestic"

class 26 104

35

6

to 8

"Wilberforce "

class 32 128

44

6

to 8

All

these figures come from Tomlinson's "The North Eastern Railway. "

Stephenson's

multi-tubular boiler was represented on the Darlington railway by examples of

his "Planet" class with boiler dimensions 6 feet 5 inches in length,

2 feet 9 inches diameter and 129 tubes of 15 inches. Hackworth, by contrast,

had been content to make further developments of the single flue design. His

" Royal George " had a return flue and engines of the

"Majestic" and "Wilberforce" classes had straight flues combined

with copper fire tubes.

Hackworth

would no doubt be interested in the method of stimulating the fire. The system

of increasing the draught by leading exhaust steam into the chimney goes back

to Trevithick, but Hackworth has been credited with increasing the efficiency

of the device by tapering the orifice of the exhaust pipe. This was another

feature of his "Royal George. "

In

connection with the reference to oil, a glimpse of the Darlington lubrication

problem is seen in one of the other letters in Kitching's letterbook in which

he refers to repairing a wagon broken "in consequence of the negligence of

the Enginemen omitting to oil the axle from which neglect the axle was nearly

through so that it was unable to sustain the weight of the coal any longer and

broke."

The

question of "smoke and particles of inflammable matter" was perhaps

too topical. From the beginning the Darlington railway had encountered strong

opposition from the local aristocracy and the company had only just

successfully emerged from an indictment on the grounds of the nuisance caused

by the use of locomotive engines "which exhibited terrific and alarming

appearances" when travelling at night, emitted "unwholesome and

offensive smells, smokes and vapours," and made "diverse ]oud

explosions, shocks and noises. " There was also the question of the damage

done to wooded plantations by sparks from the engine. The Darlington solution

was to reduce speed through the plantations to 5 m.p.h. and have a watchman

stationed there to report offending engines which could be identified by a

large numbered board projecting from the funnel.

Finally

on the question of wrought iron wheels: in England the credit for first putting

wrought iron tyres onto cast iron wheels has been claimed for both Hackworth

and for Nicholas Wood of Newcastle upon Tyne, both in 1827. William Losh of

Newcastle took out a patent for malleable iron wheels for railway carriages on

August 31st, 1830. In his "The British Steam Locomotive" Ahrons

describes Stephenson's wheels of the period 1830-37 in this way: "In the

engines . . . the hollow boss and rim were of cast iron. The rim was also with

a hollow groove round it to lessen the weight. The spokes were wrought iron

tubes tapering from 2-1/4 to 2 in. diameter cast into the boss and rim, and

arranged so that alternate spokes slanted in opposite directions. The tires of

the driving wheels, 5 feet diameter, had a mean thickness of only about 1-7/16

in., all tires were of wrought iron, welded. The driving tires of Stephenson's

engines had no flanges." Hackworth's engine wheel was designed for the

"Royal George" and it was used on nearly every engine on the Stockton

and Darlington railway for many years. It was cast iron with either a chilled

face or with wrought iron tyres shrunk on. As regards wagons, however,

according to R. Young in "Timothy Hackworth and the Locomotive," the

chaldron wagon wheels remained little changed in design between 1825 and 1856

although the company came to have between 1,500 and 1,600 in use. They all had

cast iron wheels and in severe frost would break 1,200 to 1,500 of these in a

month.

Presumably

it was the relative cost which kept the cast iron wheels in use. It certainly

could not have been the fossilizing effects of tradition for there was no

tradition to fossilize. That is another aspect of comparative Anglo-American

history which has often been overlooked, namely that the history of the Eastern

United States in many economic respects is not the history of an organisation

younger than the British but contemporary with it. Whatever there was on the

Baltimore and Ohio there certainly was pioneer improvisation on the Stockton

and Darlington. The young Quaker who copied this letter had learned about

engines by working among them. In 1833 he was repairing them. Soon he was to

repair one so extensively that he really rebuilt it. After that he began

building in his own right. In this work he was helped by his brother and some

survivals give an inkling of the spirit in which they worked. There is still in

existence a little book called "Roberts's Mechanics' Assistant, or,

Universal Measurer." It is dated 1833 and signed on the flyleaf by one of

the Kitchings. This assistant to locomotive engineers announced itself as being

"Adapted to the Use of Engineers, Mill-Wrights, Iron Founders, Smiths,

Forgemen, Rollers and Slitters of Iron, Timber Merchants, Architects,

Surveyors, Joiners, Carpenters, Masons." Its contents included the

"Use of the common slide rule, with examples" and it had an appendix

"exhibiting the strength of materials, and a correct Method of calculating

the Horse Powers of a Steam Engine." Similarly their letters of the time

contain such requests as one to forge the iron shafts "to the specified

diameter as near as you can." Or again there was this instruction:

"be particularly careful in placing the columns on which the boiler rests

very trim and square otherwise it will cause us a great deal of unnecessary

trouble and expense.... N. B. Get as large a plate on the top of the main tube

as you can. Only just leave sufficient room to rivet and no more and also keep

the main tube the full size inside according to the plan."

Furthermore,

if the young American who came to Darlington armed with the Baltimore letter

took a trip down the Stockton and Darlington railroad he would have found the

passenger traffic only just taken over by the company from private contractors

and the goods traffic let out on contract. If he had continued further down the

river Tees than Stockton he would have entered that most American phenomenon—a

railhead town, this one named Middlesborough and growing apace on what had

been, a few years before, the land of a solitary farm.

G.

A. PETCH.

King's

College in the University

of

Durham, England.

The

letters quoted in this article are reproduced by courtesy of Whessoe Limited,

Darlington, successors to the original Kitching firm.

Return to the Hopkin Thomas,

B.M.R.R. Master Mechanic page

About

The Hopkin Thomas Project

Rev.

December 2011