MERTHYR TYDFIL - IRON METROPOLIS

1790-1860

OWEN, JOHN A., Merthyr Historian, Vol. 1, Merthyr Tydfil Historical

Society, 1976

Before

discussing the emergence of the Merthyr Tydfil district from the late 18th

century as the largest and most powerful iron manufacturing area in the world,

it is important to look very briefly how the four great ironworks started.

Dowlais

Works

Started as

the "Merthir Furnace" from the prospecting of one man Thomas Lewis,

of Llanishen, the owner of the Pentyreh Furnace and other forges. He obtained

leases in coal and minerals in Dowlais district from Lord Windsor for ₤31

per annum for 99 years. He then formed a consortium of nine partners,

merchants, gentlemen, etc. in September 1759, to operate and trade as iron

masters for a stock of ₤4,000.

From the

start the venture was very short of ready cash to operate the business and

until 1767 a committee was appointed to run the affairs of the concern. In 1767

a Manager was appointed, namely John Guest. In 1782 John Guest became a partner

acquiring 6/16 share in the works. From this time on the Guests dominated both

the partnership and the direction of business, although until the early part of

the 19th century not in a commanding position.

The

Plymouth Works

So named

because it was built on land leased from the Earl of Plymouth in December of

1763 to Isaac Wilkinson and John Guest. But because of early difficulties, i.e.

getting farmers and tenants to move from their land, they sold their rights to

Anthony Bacon, a rich London merchant in 1765/1766. (There is no evidence that

Guest & Wilkinson actually started production.) Then in 1788 the Court of

Chancery granted a lease on behalf of Anthony Bacon's second illegitimate son

who had inherited the Works to Richard Hill from Christmas 1786 for 151, years.

Hill was the brother-in-law of Anthony Bacon and had been managing the furnace

from 1784. When he took over the Works it consisted of one small furnace,

worked by two giant bellows, waterwheel operated.

Cyfarthfa

Works

In 1765

Anthony Bacon and William Brownrigg of Whitehaven took out a lease to build a

furnace. In 1766/67 the first furnace appears to have been built by one Charles

Wood for the partnership. A thong it seems that a forge was built in 1766 using

pig iron from the Plymouth Works, also during the building of the furnace many

castings were supplied from the Plymouth Works. The furnace was further

extended in 1773 by building a mill for boring canon to supply the Board of

Finance and through this venture in 1777 a London merchant became a partner,

namely Richard Crawshay. In 1783 Bacon leased his mill to Francis Humphrey, the

owner of a furnace near Broseley, Staffs, but Bacon kept the furnace and

stipulated that Homphrey had to buy his pig iron from him. About the same year,

1783, Bacon leased his estate and furnace to Crawshay for ₤5,000 and

other portions to Homphrey, Hill, Lewis and Tait. Also it has been stated that

in October 1784, the forge and cannon boring mill were leased to one David

Tanner. Whatever, from Christmas 1786 for a term of nine years, the Cyfarthfa

furnace was leased to Richard Crawshay, William Stevens and Joseph Cochshutt at

the yearly rental of ₤1,000.

Penydarren

Works

Came into

being in February 1784, for 99 years lease under the ownership of the three

sons of Francis Homphrey-Jeremiah, Thomas and Samuel, and George Foreman of

London. The same Francis Hornphrey who had leased the cannon boring mill from

Richard Crawshay. He must have recognized the value of the opportunities

presented within the district, hence went into business in Merthyr. He already

had interests in a furnace in Broseley, Staffs., where John Guest was from, so

besides being acquainted with Cyfarthfa, he probably discussed local trade with

Guest whom he leased his large mineral tract from anyway. The Management of the

Works was taken on by two of the brothers, namely Jeremiah and Samuel by 1786.

It was they who built up the Works.

Merthyr

District 1790

By this time

all the four ironworks were established. Granted they were in different stages

of evolution and development, but nevertheless all in operation.

Transport was

still the greatest problem, although the odd mule train system of carrying had

ceased since 1771 when the road straight down the valley to Cardiff was opened.

The sheer volume of output from the Works completely clogged this slow and very

costly means of cartage. Hence, in 1790 the first of a few very significant

moves was made that coupled together, exploded the productivity capacity of the

existing ironworks, and wrote the name Merthyr Tydfil in letters of fire.

Namely, the act for the Glamorganshire Canal was passed and work started

immediately on its construction. It took four years to complete and was ready

to use in 1794 by which time the export in iron out of Merthyr was accelerating

daily. The other factor was the tremendous development at Cyfarthfa of Cort's

dry puddling process for making wrought iron (patented in 1784). It was at

Cyfarthfa that the process was perfected and the use of rolling mills for mass

producing bar iron. It was that Works which took the lead in manufacture and

greatness to start, from 10 tons of bar iron per week in 1787 to 200 tons per

week in 1800. All the Works produced pig iron and bar iron which became the

staple product for many years.

1800

At the turn

of the century all the ironworks were consolidated, although apart from

Cyfarthfa, the other three, i.e. Dowlais, Plymouth and Penydarren, were

struggling in matters of production and capital. In 1802 Cyfarthfa made a

profit of ₤36,000 and was the largest manufactory of its

kind in the world.

In 1803

Cyfarthfa had six furnaces in blast and was described by Malakin as the largest

ironworks in the kingdom or for that care in the world. Although two of the

furnaces had been built at Ynysfach in 1801, completely separate from the main

Works, eventually there were four on this site. In 1806 Dowlais had three

furnaces in blast and produced 5,432 tons, blast to furnace was supplied by a

double acting steam engine. In the same year Plymouth Works had two furnaces in

blast and produced 3,952 tons. In 1807 Plymouth erected a third blast furnace

when it became known as the Plymouth Forge Co.

This Works

was always noted for the very high quality of pig iron and bar metal. The

metallurgical analysis of its products was very closely monitored by Anthony

Hill.

1810's

By 1811

Cyfarthfa was a gigantic concern where travellers described the buildings of

the furnace as "elegant in form and where is the only building in the

world which has a complete iron roof, where iron is converted into every

possible use, even iron barges" (a gross exaggeration as the products were

almost solely pig iron, No. 2 bar or tram plates). When Richard Crawshay died

in 1810 he left a fortune in excess of ₤200,000. The Works were valued at

₤100,000 in 1809, hence a good deal of his wealth came from his merchant

house in London. The output from five furnaces in 1814 was 9,600 tons per

annum. Between 1817 and 1819 William Crawsbay became the sole owner of the

Cyfarthfa Works buying out his relations, the Baileys and Benjamin Hall. By

this time the capital of the business was in the ₤200,000 mark. Although

between the years 1813-1819 ₤250,000 to ₤300,000 was spent from the

profits of the London merchant house in securing sole control of the Works at

Cyfarthfa and increasing its production capacity, i.e. new blast furnaces,

rolling mills and ₤4,000 alone in a vast new water wheel to supply power

to the Works. In 1816 the Works produced 15,000 tons of pig iron from five

furnaces, but due to the slump in trade, a large proportion was not being

converted into bar iron due to the very low prices prevailing; hence this large

Works and its proprietor was already controlling prices and regulating the

demand for iron. It was a period to tighten the belt and await for the tide to

turn once again in a profitable direction. Meanwhile at Penydarren, progress

had been much slower with less drive and innovation from a production point of

view. In 1815 the yearly output was 7,800 tons from three furnaces. Although

Penydarren had assured everyone of her place in history with Richard Trevithick

and his high pressure steam engine which first ran on rails from Penydarren to

Abercynon on 21st February 1804. Plymouth on the other hand by 1815 was making

7,800 tons from three furnaces and by 1820, 7,941 tons from five furnaces. By

this time the smaller ironworks were feeling the pinch in terms of capital,

output and technical expansion. Both Plymouth and Perydarren concentrated on

the more quality aspect of the pig and bar iron worked and later in high

quality rails in small quantities. It was the giants of Cyfarthfa and now

Dowlais that were the mass production side of the industry with huge works,

massive machinery and teeming thousands of employees.

By the year

1815 Dowlais was dominated by one man, Josiah John Guest. The early years of

committee management, lack of working capital and no directional policy were

all over. In 1815 the five blast furnaces produced 15,600 tons of pig iron

yearly. Whilst by 1823 the ten blast furnaces were producing 22,287 tons of pig

iron. From this time on Dowlais was to expand and develop into the largest and

best ironworks in the world.

The whole

Merthyr area was Ironworks Dominated. Each separate works produced a

surrounding area in microcosm of each other. The big house of the ironmaster,

schools, churches, chapels, public houses, workmen's houses. They were the

precursors for all our accepted living environments to-day, in all crude mini

welfare states. The whole Merthyr area had the biggest, best and worst aspects

of an emergent industrial society, which was trying to adapt to an unknown

future. Merthyr was a frontier town in all aspects. Housing, slums, endemic and

contagious diseases, great wealth and poverty and magnificent technical

evolution and invention.

1820's

In 1820 the

four Merthyr ironworks were sending down the Glamorgaushire Canal to Cardiff

46,756 tons (chiefly wrought iron, an added value product as opposed to common

pig iron), out of a total of 150,000 tons of pig iron output for the whole of

South Wales. By 1840 the comparable figures were 109,777 and 505,000 tons

respectively. This figure of 505,000 tons produced in South Wales represented

38% to 39% of the total pig iron output of Great Britain. Therefore the Merthyr

district made approximately 8% of the total for Britain from four Works. Then

in 1821 Dowlais started to make the key product that would unlock the door to

the Merthyr district's greatness and secure vast profits for the ironworks,

namely "rails" for the Stockton and Darlington Railway, the first

passenger line in the world. All the Works by 1830 had taken to the manufacture

of iron rails in some degree or other.

1830's

In 1830

Penydarren had already made the cables of flat-bar link iron for the Menai

Straits suspension bridge of Telfords and rails for the Liverpool and

Manchester railway. Dowlais in the same year laid out a whole new special rail

rolling mill to mass produce wrought iron railway rails (the Big Mill).

The periods

of early railway construction created an enormous demand for railroad

"furniture" (rails, chairs, etc.) and was undoubtedly the greatest

stimulant to the expansion of industry for decades. The opportunity the Merthyr

ironworks grasped with both hands. By 1836 Dowlais was exporting rails all over

the world and making 20,000 tons of this product alone per year. The rapid

expansion of the trade and industry continued with frightening speed to the

zenith of the district's manufacturing capacity and influence in iron. A great

aid to this expansion was the completion of the Taff Vale Railway from Merthyr

to Cardiff in 1841, for the ingress of raw materials and export of finished

goods at speed.

1840's

By 1845 the

Dowlais Works was the biggest and greatest ironworks in the world with 18 blast

furnaces producing 88,400 tons yearly, 1,700 tons weekly, with the finished

products in rails and bar iron 1,600 tons weekly, and 7,500/10,000 persons were

employed. Whilst Thomas Evans the sales agent was paid ₤l,000

per annum and traveled the world to obtain orders for rails, and where the rest

of the world's industrialists beat a path to the Door of Dowlais House so they

could view the gigantic concern, see its marvelous technical developments, then

go home and copy it if they could.

Cyfarthfa had

11 furnaces in blast producing 45,760 tons of iron and the new steam driven

rolling mill produced 2,500 tons of rails per month and cost ₤25,000 to

erect and equip.

Penydarren

had six furnaces in blast (seven in 1848) and produced 15,600 tons of high

quality iron but the Works had not expanded or developed as they had earlier

promised due to the lack of capital and management direction. This ironworks,

the last to emerge in 1784, would be the first to close in 1859, the high water

mark being its association with Richard Trevithick in 1804.

Plymouth

Works had steadily progressed under the excellent guidance of Anthony Hill from

his managership in 1826. He was a first class businessman and more important an

excellent metallurgist, so much so that the iron produced in the Works was

always. oversubscribed in orders. It was the standard quality to which all

other South Wales iron was judged. The Works had developed South from Merthyr

in a very fragmented strip development, which on the surface was not conducive

to efficiency, but for them it worked, because they were always relatively “small

" and did not overdevelop outside their capacity for quality iron. The

original Plymouth Works in Merthyr had five furnaces ultimately. The Duffryn

furnace site started in 1819, was finally finished in 1850 when No. 10 blast

furnace was blown in. Whilst the Pentrebach Works in-between consisted of

puddling furnaces and rolling mills, the last big investment being made in

1841. In 1846 the eight furnaces in blast produced 35,198 tons. This Works

continued to prosper up until 1862 when Anthony Hill died. The firm which took

it over either through lack of expertise or business management, allowed the

concern to run down completely. This was accelerated when they attempted to

compete against the giants of Dowlais and Cyfarthfa in the mass produced railway

furniture market, whilst abandoning their quality product iron in the process

which could have saved them.

During the

latter half of the 1840's and throughout the fifties, the wind of change

started to blow through the Merthyr ironworks district. At Dowlais there was

the lease drama in 1848 when it was thought that Sir J. J. Guest was not going

to carry on manufacture and close the Works down, but he renewed it at the last

event for over ₤5,000 rent per annum and ₤30,000

royalties, a far cry from ₤31 per annum he paid up to then. Cyfarthfa

continued as strong as ever in the same period with their lease due for renewal

in 1864.

1850's

Meanwhile

Plymouth, whilst Anthony Hill lived, refined top grade iron. Penydarren on the

other hand slowly limped to oblivion in 1859 as a manufacturing entity, when

the Dowlais Iron Co. bought them out for ₤59,875, solely to retain their

old mineral district at Cwmbargoed for coal production.

But the

middle of the nineteenth century produced a terrific traumatic shock for the

whole world of manufacturing industry. In 1856 Henry Bessemer patented a

process for producing malleable iron, using a blowing cylinder, without

recourse to coal or charcoal. The Bessemer process as it became known was the

dawn of the steel age and although no one then could forecast the impact the

event would have, it was the beginning of the end for the mass produced iron

manufacturing age - Dowlais as ever with its technical expertise took out the

first license from Bessemer and Longsdon to use the patent. Although for many

technical reasons the process was not successful at first, but by 1865 it had

its steelworks, which were to resound throughout the world the same as the

earlier ironworks did. Cyfarthfa did likewise but much later in 1884, with a

long shut down period in between. Plymouth never built a steelworks due to a

failure of the whole manufacturing business in 1875/80.

Thus by 1860

the glory of the great Merthyr ironworks district was fading fast, buried by

technical and economic changes in manufacturing processes.

The

industrial rise of the Midlands and the north of England was at hand. It did

not end at this date but between 1860 and 1880 a completely different

manufacturing philosophy and business emerged, with the change to steel taking

place and the emergence of the South Wales coal industry.

The

entrepreneurs of the local iron industry had mostly all been Englishmen,

merchants, traders and technical adventurers, who had vision, ability and business

acumen to create vast fortunes for themselves and introduce tremendous

technical innovations and expertise which the rest of the world followed for

many years, also the doubtful advantage of mass integrated industrial

communities with all the ignorance, disease and exploitation they portended.

Business Expansion and

Population

But for all

that, it is well for us to remember the names of the main proprietors of those

Works.

Lewis/Guest Dowlais

Bacon/Hill Plymouth

Bacon/Crawshay Cyfarthfa

Homphrey /Foreman

Penydarren

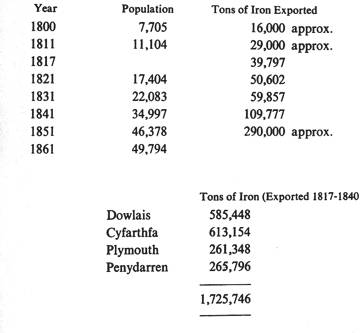

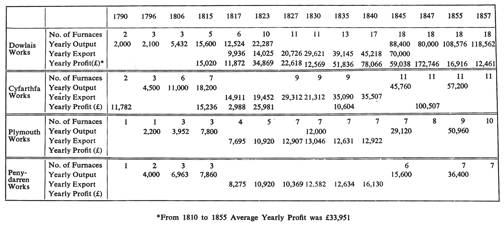

Also some of

the statistics of iron exported down the Glamorganshire canal from 1817 to

1840.

References

(Abridged)

1. The

Dowlais Iron Co. Letters 1782-1860. Edited by Miss M. Elsas, Glamorgan County

Archivist 1960.

2. A Short History

of the Dowlais Ironworks, J. A. Owen 1972.

3. Mines,

Mills and Furnaces, Morgan Rees 1969.

4. The

Penydarren Ironworks, Miss M. S. Taylor 1969 (Glamorgan Historian Vol. 3).

5. The Canals

of South Wales and the Border, Charles Hadfield 1967.

6. The

Industrial Development of South Wales, A. H. John 1950.

7. The

Crawshay Dynasty, John P. Addis 1957.

8. The

Plymouth Ironworks, Clive Thomas 1972.

9. The

History of Merthyr Tydfil, Charles Wilkins 1908.

10. The Early

History of the Old South Wales Ironworks, John Lloyd 1906.

11. A Guide

to Merthyr Tydfil, T. E. Clarke 1849.

12. A History

of the City of Cardiff, W. Rees 1969.

13. The Iron

Manufacture of Great Britain, William Truran 1855.

14. The

Economic History of the British Iron & Steel Industry 17841879, Alan Birch

1967.

Return

to the Merthyr Tydfil Page

About

the Hopkin Thomas Project

Rev.

November 2009