Philadelphia

A 300-YEAR HISTORY

A Barra Foundation

Book

W. W. NORTON &

COMPANY

NEW YORK - LONDON

E D I T O R

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Nicholas B. Wainwright

Edwin Wolf 2nd

EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS

Joseph E. Efick

Thomas Wendel

Copyright @ 1982 by The

Barra Foundation. All rights reserved. Published simultaneously in Canada by

George J McLeod Limited, Toronto. Printed in the United States of America.

FIRST EDITION

The text of this book is

composed in photocomposition Janson Alternate, with display type set in Roman

Compressed No. 3 and Garamond Old Style. Composition by The Haddon Craftsmen,

Inc. Printing and binding by The Murray Printing Company.

BOOK DESIGN BY MARJORIE

J. FLOCIC

ISBN 0-393-01610-2

Ed.: Portions of

the extensive chapter, The Age of Nicholas Biddle, have been

excerpted for the purpose of giving an impression of the development of the

City of Philadelphia at the time of the arrival of the Hopkin Thomas family in

1834.

(Note that the

original of this text is thoroughly annotated – these citations have not

been included in this excerpt – see the original publication for

details.)

J. McV, 8/2008.

1825-1841

by Nicholas B.

Wainwrigbt

Philadelphia

is a city to be happy in.... Everything is well conditioned and cared for. If

any fault could be found it would be that of too much regularity and too nice

precision.

-

NATHANIEL P. WILLIS

******

1825

On

the surface all seemed well with the city, were one content with limited

aspirations. At a testimonial dinner in 1825 Commodore John Barron held forth

his glass and declaimed: "Philadelphia-justly acknowledged to be the first

in the arts, and second to none in whatever can contribute to the grandeur, respectability,

and comfort of a city!"" Yet in the arts Philadelphia was fast losing

her place, and she had already lost her rank as the country's largest city and

most important trading center.

I

To

be sure, numerous vessels continued to ascend the Delaware-about 500 a year

from foreign ports, two to three times that many plying the coastal trade.

Unloaded on the wharves that lined the city's front were cargoes of rice,

cotton, and tobacco from the South; spermaced oil from New Bedford; horse hides

from Montevideo; coffee from Brazil and Java; toys from Germany; linen from

Ireland; rum from St. Croix and Jamaica; sherry, madeira, claret, muscatel, and

teneriffe from their points of origin; armagnac, bordeaux, and brandy from

France; whisky from Scotland; mahogany from Nicaragua and Santo Domingo; indigo

from Bengal; pepper from Sumatra; and opium from Turkey. The most princely

imports of all came from Canton, consigned to merchants specializing in that

trade. Every year about a dozen richly laden ships hove into port from the

Pearl River. Shortly after the ice had melted in the early spring of 1825, the

Caledonia sailed majestically upstream to discharge her store of silks, curry

powder, window blinds, umbrellas, porcelains, camphor trunks, bamboo baskets, fans,

kites, fireworks, and vast quantities of tea-Hyson, Gunpowder, Imperial,

Pouchong, Souchong. These Chinese luxuries found a ready market, but

Philadelphia had little to export to China in exchange. Her ships went out

lightly freighted with gold and silver to balance her trade with the Orient. As

a consequence her merchants sought substitute markets. By 1820 English and

French porcelain had largely supplanted Chinese articles in that line and by

1825 the city had its own porcelain factory, where the famous Tucker china was

made. Tucker's masterpieces were said to surpass European imports "in

soundness of body, smoothness of glazing, and beauty of lustre.”

Vase made at the

Tucker porcelain factory (1826-1838), c. 1832-1835. The building painted on the

vase was the Tucker factory on the Schuylkill riverfront near Market Street.

Part

of the bullion exported to China was gained in Philadelphia's favorable trade

with Latin America. In 1825 about a third of her foreign exports - flour,

lumber, furniture - went to Mexico and South America, bringing back much hard

money in exchange. Henry Pratt, Matthew Bevan, and Manuel Eyre were prominent

in this trade, which was the largest with Latin America of any North American

port. Trading ties brought social ties. Many young South Americans and Cubans

were sent to school in Philadelphia, among them Simon Bolivar's nephew

Fernando, who attended Germantown Academy in the mid-1820s.

In

the order of their value, the city's largest foreign exports in 1825 went to

Mexico, Cuba, and England. In the same order, the largest foreign imports came

from England, China, and Cuba. Most of this trade, which was so vital to the

city's economy, was carried in American ships, many of them Philadelphia-owned

and built in the extensive Kensington and Southwark yards. Six to ten thousand

tons of new shipping slid annually down their ways into the Delaware. In 1825

the 6292 tons launched were represented by seven ships, eleven brigs, two

schooners, one sloop, and one steamboat.

Most

of these vessels were built for the coastwise lines which furnished regular

service between Philadelphia and New York, Boston, Baltimore, Charleston, New

Orleans, and other ports. The city also had two Liverpool lines, one owned by

Thomas P. Cope and the other by John Welsh. The Liverpool packets, with their

ample cabin space - the trip to England cost $93 - and large holds for cargo,

were among Philadelphia's most highly prized vessels. Cope's Tuscarora, Montezuma, Algonquin, and Alexander and the "New Line's" Colossus, Delaware, Julius Caesar, and Bolivar were proud sights as they cleared the

river under clouds of canvas.

II

But

commercially the city might have done better had she not been so relaxed and

comfortable. Philadelphia's easy-going southern overtones were in marked

contrast to the hurly-burly, the raucous bustle of New York. Her ties with the

South were close. During the sickly season families from South Carolina and

Virginia summered in her vicinity, and there was much inter marriage. From

Charleston came Draytons, Hugers, Middletons, and Izards, some of them to

remain as Philadelphians. The Virginia contingent, Carters, Tuckers, Pages,

Riveses, was most distinguished. In addition much of Philadelphia's business

was with the South. Seasonal visits filled her hotels with southern and western

merchants, come to replenish their stocks of merchandise by large purchases

from the local commission dealers.

Out-of-towners

looked forward to their Philadelphia visits. The city was so neat and clean,

its market the best in the country. The better stopping places, such as the

United States Hotel, facing the Bank of the United States across Chestnut

Street, were noted for their cuisines. Joseph Head's Mansion House at Third and

Spruce Streets boasted French cooking, a style evidently considered unrivaled,

while Parkinson's celebrated restaurant at 161 Chestnut Street advertised

"Coffee ą la mode de Paris." Of all the exponents of the French mode,

M. Latouche was unquestionably the leader. For eight years Latouche had cooked

for the prince D'Ecmuhl, then for three years he had presided over the kitchens

of the duc de Rovigo. Coming to America, he had been employed in Washington by

the Russian minister before settling in Philadelphia as a restaurateur and

caterer. In addition to the oyster cellar he conducted under his Market Street

restaurant, well stocked with the choicest wines, Latouche offered take-out

dishes such as oyster pies (100 oysters), $1.25; fourteen mutton chops, $1.00;

eight quail, roasted and larded, $1.00; sixteen pounds of beef ą la mode,

$3.00; and hogs' heads, trimmed with jelly, $2.50. The prices seem low, but

when it is realized that the pay of Philadelphia weavers averaged only five

dollars a week, there could not have been too many calls for hogs' heads from

the workingman.

******

111

Although

parties were frequent and life pleasant, the city lived to an excessive extent

on the diminishing returns of a direction given to its economic life by men

long since dead. A bold, aggressive new leadership was necessary lest

Philadelphia's drowsiness lapse into a deep slumber. Profoundly agitated at the

portents of the times, the city's men of business fully recognized the

seriousness of the crisis. Comparing the past with the present, they were faced

with figures that proved how badly their city had fallen behind her rivals.

Historically

Philadelphia had prospered as the "bread basket" of the colonies and

the young Republic; but the westward shift of population had cost her primacy

in the export of flour. This was not because Pennsylvania was producing

relatively less - 59 of the 100 members of her House of Representatives were

farmers in 1825 - but because her flour was slipping away to other ports. The

produce of the western part of the state now went down the Susquehanna to Port

Deposit, at the head of tidewater navigation. There, thousands of barrels of

Pennsylvania flour and whiskey and vast quantities of wheat, corn, pork, and

bacon were loaded on schooners for shipment to Baltimore. Fleets of lumber

rafts, which had floated downstream, were towed off to the same place. In 1820

Baltimore had exported 577,000 barrels of flour, already exceeding

Philadelphia, which had only 400,000 barrels to ship out, but was

still far ahead of New York's 267,000. The measure of Philadelphia's decline in

this trade is seen in the comparable figures for 1825: Baltimore, 510,000;

New York, 446,000; Philadelphia, 354,000. The completion of the Erie Canal, as

Philadelphians were aware, would not improve the situation. In 1828, for

example, New York was to ship out 722,000 barrels;

Baltimore,

546,000; Philadelphia, 333,000

Brought

up in the belief that their prosperity depended on foreign commerce,

Philadelphians were dismayed at how, year by year, the shipping tonnage

registered at their port was falling behind their competitors. Tonnage figures

for 1825 showed New York in the lead with 304,484; Boston next with 152,868;

Baltimore totaling a surprising 92,050; and Philadelphia trailing with 73,807.

As far as the rivalry between New York and Philadelphia was concerned, the

figures were in balance with the values of their foreign imports and exports.

In 1824 New York's imports were valued at $36,113.000 - Philadelphia's at

$11,865,000; New York's exports came to $22,897,000 - Philadelphia's to

$9,634,000. The state of New York, having surpassed Pennsylvania in population

before 1820, had a growth rate in the 1820s twice that of Pennsylvania, and

that rate approximated the growing difference in size between her metropolis

and Philadelphia.

IV

Philadelphians realized that the economic

health of their city depended on internal improvements, access to the interior

wherein lay the future wealth of America. The turnpike spree was still in

progress - by 1832 Pennsylvania chartered 220 turnpike companies which had

built some 3000 miles of roads - but for the shipment of heavy freight

turnpikes were outmoded; canals were now the cry, and New York was in the lead.

Her great state-built canal, 362 miles long and eight years in the building,

was completed in 1825. Philadelphians had financed two lesser improvements: the

Schuylkill Navigation Company, which was opened to Reading in 1825, and the

Union Canal, which would soon permit canal navigation between Reading and the

Susquehanna. Philadelphians were also heavily interested in the Chesapeake and

Delaware Canal, but these three improvements did not reach the heartland of the

country, the great western reaches that New York had tapped through her Erie Canal.

Determined

that their city should not lose what was left of her commercial prestige, a

group of Philadelphians, headed by John Sergeant, eminent lawyer, congressman,

and champion of Henry Clay's American System, had founded the Pennsylvania

Society for the Promotion of Internal Improvements late in 1824. The activities

of this society resulted in a public meeting in January 1825, presided over by

Chief justice William Tilghman. Sergeant, the principal speaker, pointed out

that canal navigation between the Delaware and the Susquehanna would soon

become a reality, and that this development called for the next step - water

communication between the Susquehanna and the Allegheny. Furthermore, from the

Allegheny a canal to Lake Erie should be undertaken, and built at the expense

of the state. The meeting enthusiastically endorsed Sergeant's resolutions. A

suitable memorial to the legislature was prepared, and William Strickland was

sent abroad by the internal improvements society to procure information on canals

and railroads. "A large proportion of the western trade has been withdrawn

from this city," reported the improvements society, "and the present

exertions are calculated not merely to regain what is lost. The struggle

assumes a more serious aspect. It is to retain what is left.”

Philadelphians

next convened_a canal convention at Harrisburg, attended by 113 delegates from

thirty-six counties. After a year of ceaseless effort by Sergeant and his

friends the legislature passed an act that opened the way for the building of

the canal at state expense. Ultimately the state improvement program embraced a

railroad from Philadelphia to Columbia, the point on the Susquehanna where much

of the western produce reached the river, and various lesser projects. A 394-milc

"main line" of State Works was projected and completed in the

mid-1830s: the Columbia Railroad, 82 miles; the Eastern Division Canal from

Columbia to Hollidaysburg, 17 miles; the Allegheny portage Railroad over the

mountains to Johnstown, 37 miles; and the Western Division Canal from Johnstown

to Pittsburgh, 104 miIes.

Long

before all this was accomplished Strickland had returned from his foreign

travels and published his influential Reports on Canals, Railways, Roads,

and Other Subjects,

which so much favored railroads over canals that his sponsors required him to

tone down the emphasis.

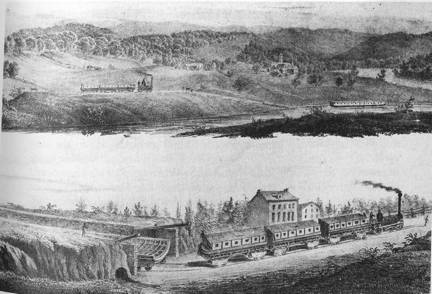

Advertisement for

portable iron boats used in the 394-mile system of rail and canal

transportation between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Lithograph by S. Duval

after George Lehman (d.1870), c.1840.

V

After all, Pennsylvania was by this time

committed to canals, and it was especially through the Schuylkill Navigation

Company, a gilt-edged Philadelphia-owned investment, that the city was

experiencing the promise of better days. Back in 1817 the company's managers

had suggested the possibility that coal might eventually be carried on the

canal; they had had no concept that, shortly after it went into operation, coal

would constitute two-thirds of its traffic. Flour, lumber, whiskey, and all the

multitude of country products were to take a back seat to anthracite. In 1826

coal accounted for half the canal's total freight Of 32,000 tons;

in 1840, of the 658,000 tons brought down the river, 452,000 came from

Schuylkill County mines .

The Columbia Rail

Road, part of the State Works, from Daniel Bowen, A History of Philadelphia

(Philadelphia, 1839).

The

first coal of consequence to reach Philadelphia had been 365 tons brought down

the Delaware from the Lehigh area in 1820. Under the guidance of its manager,

Josiah White, the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company struggled to make the

mines at Mauch Chunk profitable. When the state agreed to build the Delaware

Division of the Pennsylvania canal system, work, began in 1827 on the Lehigh

canal planned by White and Erskine Hazard, and within a few years both projects

were completed. At Easton, the Delaware Division of the state-owned works

united with Josiah Wright's heroic enterprise, and provided slack-water navigation

down the Delaware to tidewater.

Coal

worked miracles in Philadelphia. The city had always been a wood-burning

community, its houses heated by hickory, oak, and maple. Wood was used for

cooking and to fire the boilers of the recently invented steam engines -indeed,

the appearance of steamboats on the rivers had caused the forests to recede, so

great was their hunger for fuel. At first there was much suspicion and dislike

of coal, but as stoves, grates, and furnaces were perfected for its use it won a

grudging acceptance based on its cheapness. In the late 1820s central heating

was introduced into some Philadelphia homes, but the change from wood to coal

in domestic uses came slowly; in 1833, $741,000 worth of wood was burned in the

city, only $404,000 of coal.

The

most notable physical change imposed on Philadelphia by the coming of coal was

to be seen along her Schuylkill River front, where a solid mass of wharves was

built. These were usually crowded with canal boats from the mines and bristling

with the masts of the coastal shipping which distributed anthracite to ports

along the Atlantic seaboard. Philadelphia's first exports of coal went out in

four vessels in 1822. In 1837 some 350,000 tons in 3225 carriers cleared the

port for coastal destinations. Gone forever was the old colonial concept that

the city's economic life depended on foreign trade.

An

innovation in these years, made possible by the abundance of coal, was the

application of steam power to industry. Philadelphia led early in the manufacture

of steam engines for this purpose - stationary engines as opposed to those

designed for steamboats and locomotives. By the late 1830s the role of the

stationary engine was fully appreciated and steam was being used in every

conceivable type of manufacture.

To

keep up with New York, Philadelphians had done all they could to encourage

manufacturing, but waterpower for mills was limited, as neither the Delaware

nor the Schuylkill had sufficient fall to generate a great amount of power.

Steam supplied the alternative. By 1838 there were more steam engines in

Pennsylvania than any other state, with nearly all of those in Philadelphia of

local manufacture. Made by forty-four different individuals or firms, they

serviced twenty-five types of mills, supplying the power for such enterprises

as carpet weaving, breweries, flour mills, and the iron industry. Rush &

Muhlenberg and Levi Morris were among Philadelphia's leading engine-makers, and

so famous were the city's workers in this trade that Joseph Harrison, Jr.,

later recalled: "Philadelphia skill has been sought for to fill

responsible places in all parts of the United States, in the West Indies, in

South America and in Europe, and even in British India."

Now

that factories were no longer dependent on the geographical necessities of

waterpower, manufacturers were free to concentrate their mills wherever they

wished, in Frankford and Kensington, where waterpower had first attracted

industry and which had become textile centers, but also throughout the city.

The stationary steam engine helped make possible another long step in changing

Philadelphia from a commercial to a manufacturing town with all the

implications that would have for the city's future.

VI

Philadelphia's

prosperity continued, however, to depend in large measure on her port, and

various steps were taken to make it more available to the outside world. A

canal connecting Delaware and Chesapeake Bays, it was believed, would greatly

enhance Philadelphia's southern commerce, and into such a project

Philadelphians poured a great deal of money. In the fall of 1829 the

thirteen-and-a-half-mile length of the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal was

completed. To celebrate its opening, a large party of Philadelphians embarked

on the steamer William Penn, chartered by the canal's directors. On board were

two companies of militia in full dress, Frank Johnson's band, and the best

caterer available. The paddlewheel-vessel churned her way down to Delaware City

at the eastern end of the canal, where her guests left for their tour of

inspection.

The

year that saw the completion of the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal was notable

also for the commencement of work on the great breakwater, designed by William

Strickland, at the entrance to Delaware Bay. Storms and ice had brought

disaster to 193 vessels in that vicinity during the past twenty years, losses

that would not have occurred had there been a place of shelter. Now that

Pennsylvania was at the threshold of a new era to be created by its system of

internal improvements, safe navigation of the Delaware was more than ever

necessary to protect the increased commerce that was expected on her waters.

Philadelphians believed that the canals converging on their city would provide

the flourishing interior of the nation with its shortest route to the Atlantic;

Philadelphia, they hoped, would be the place to which the western trade could

be carried at the cheapest rate.

There

was, unfortunately, a fly in the ointment; Philadelphia was not an ice-free

port. The winter of 1831-1832 was unusually severe, and the port iced in. On

January 26, 1832, there were no fewer than 126 vessels listed as ready to sail

as soon as the ice broke up. The eventual departure of this large number of

ships, all sailing together, brought thousands of spectators to the wharves. It

was a beautiful sight. In 1835-1836 the solid sheet of ice that spanned the

river again kept the shipping from coming up for more than two months. Not

until the middle of March was a passage between Chester and Philadelphia possible,

and then it was hammered out by the new steamer Pennsylvania, built at

Kensington by John Vaughan & Son and not designed primarily to clear ice

but to tow up ocean-going ships from the breakwater, thereby creating "a

new era in our foreign trade." It was a cheering sight to see the white

canvas again on the river," wrote an observer. "Fully fifty square

rigged vessels arrived at the wharves, swelling the whole number of arrivals to

near one hundred." Many of the boats were loaded with firewood, which had

been in short supply. The day they unloaded, the price per cord dropped from

fifteen dollars to seven.

While

steam tow boats were a valuable navigational aid (in 1836 the Pennsylvania towed up 247 sail), the need for a real

ice boat remained. In 1837 the Delaware was again ice-fast and the public's

patience was exhausted. As usual the stoppage of trade threw hundreds of

laborers out of work and drove merchants to New York to buy their goods."

Urged on by resolutions adopted at a town meeting, the city Councils

appropriated $70,000 to build an ice boat, which was launched the following

August at Van Dusen and Byerly's Kensington yard. The next year this boat,

commanded by Capt. Levi Lingo, was battling Delaware ice piled in ridges five

feet thick.

Launchings

at Van Dusen and Byerly's and Philadelphia's other shipyards were popular,

well-attended affairs, but there never was such a launching as that of the

U.S.S. Pennsylvania

in July 1837. It attracted the largest crowd, estimated at 100,000 that had ever-assembled

in the county. Fifteen years a-building and a-setting on the stocks in the

giant ship1house at the Navy Yard, the 120-gun ship-of-the-line Pennsylvania was the largest ship in the world and

the most heavily armed man of war ever built. Designed by Philadelphia's naval

architect Samuel Humphreys, her main gun deck was 212 feet long, and her beam

58. To the delight of the multitudes clustered on rooftops and crowding the

more than 200 vessels assembled for the event, the Pennsylvania glided smoothly

down the ways. On board were several hundred guests and a German band playing

patriotic American airs. just as the vessel touched the water, Nicholas

Biddle's brother, Commodore James Biddle, a veteran of thirty-seven years in

the navy, christened her by smashing on her figurehead a bottle of Pennsylvania

whiskey made in Union County in 1829, and a bottle of madeira, hoary with age,

its label bearing a single word, the name "Cadwalader."" The

career of the Pennsylvania was not fated to be as glorious as her launching.

She was to spend many years tied up at the Norfolk Navy Yard, and there she was

scuttled in t861 to prevent her falling into the hands of the Confederates.

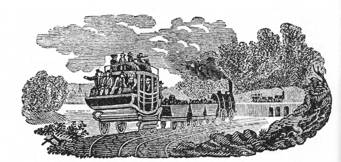

Launch of the U.S. Ship

Pennsylvania, wood engraving by R. S. Gilbert (July 1837), from A History of

Philadelphia (1839).

With

navigation improved by the breakwater, tow boats, and the ice boat, its life

stimulated by coal and other cargoes carried on the canals, the port of

Philadelphia had never been more active. About five-sixths of the shad taken by

Gloucester County's forty shad fisheries was marketed in Philadelphia. Every

year about 1000 lumber rafts containing fifty million board feet in all

descended the river from New York's Delaware and Sullivan Counties and Pennsylvania's

Wayne County.

But

the enormous increase in the city's coastal trade was accompanied by a decline

in her foreign commerce. Of her two packet lines to Liverpool, only Cope's

remained. At New York, on the other hand, many lines provided regular sailings

to a number of European ports, and it was to New York that the English steamers

Sirius and Great

Western made their way

in 1838. With the practicability of transatlantic steam navigation established,

Philadelphians yearned for steam packet service of their own, through whose

"potent aid" they could "restore our city to the first rank

among our commercial sisters ... and bring back to the shores of the Delaware

the forests of masts which in former times cheered the hearts of our fathers

and laid the broad foundations of our wealth and power. But the

$550,000required to set up a steam line could not be raised. The effort was

evidently unrealistic, based on nostalgia for the city's lost position and a

desire to regain her former prestige in commerce. Philadelphia's destiny lay in

other directions, in other kinds of wealth and economic might."

V1II

For

Philadelphia was to have as much steam power as any other city, steam applied

not to ocean-going lines but to railroads and factories, with the first locally

financed road stimulated by a Germantown gathering in October 1830. Among those

who thought that a railroad to Philadelphia would be profitable were Benjamin

Chew, Jr., of Cliveden, P. R. Freas, editor of the Germantown Telegraph, and John F. Watson, the antiquarian

whose Annals of Philadelphia,

the city's first history, had just been published. The line these men wanted

was to have a branch, crossing the Wissahickon near its mouth, to Norristown,

where mills produced 40,000 barrels of flour a year. The possibilities of heavy

freight and passenger service were so favorable, and the understanding that the

line would eventually be connected with the coal regions so well understood,

that the stock of the Philadelphia, Germantown & Norristown Railroad, when

offered for sale, proved insufficient to meet the demands of frantic

speculators who scrambled for it in riotous fashion.

The railroad celebrated the

successive opening of its divisions with much pomp. In June 1832 the Germantown

run was inaugurated with thousands of curiosity seekers in attendance and the

usual band of music. The cars, which resembled large stagecoaches, each seated

about twenty passengers inside and fifteen outside, and were drawn by horses.

The road's first locomotive, Old Ironsides,

made by Matthias W. Baldwin, was placed on the rails the following November,

but at first was used only in fair weather because its weight of a mere five

tons did not give it enough traction to hold the rails in rain. Under the

supervision of William Strickland, the Norristown branch reached Manayunk late

in 1834, and in August 1835 service was initiated to Norristown. From there,

arrangements were made with the Philadelphia and Reading to continue a railroad

along the margin of the Schuylkill.

Chartered

in 1833, the Reading was to be the masterpiece of Virginia engineer Moncure

Robinson. Financed in part with money Robinson had raised in England, the

railroad was completed to Reading in 1838, providing competition for the canal

of the Schuylkill Navigation Company. A feature of the Reading was mine-to-ship

transportation, from the coal regions to the port, for its line extended across

Philadelphia County to Port Richmond at Kensington on the Delaware, where the

railroad had its own wharves.

Rail Road Depot at

Philadelphia, Ninth and Green Streets, lithograph by David Kennedy and

William Lucas after William L. Breton (c. 1773-1855), 1832. On November 24,

1832, the United

States Gazette reported, "The beautiful locomotive engine and tender,

built by Mr. Baldwin of this city

... were for the first time placed on the road. The engine traveled about six

miles, working with perfect accuracy and ease and with great velocity. "

Not

content with a railroad to Reading, Philadelphians had their eyes on the trade

of a vast area of productive land along the branches of the Susquehanna. As

early as 1830 they were calling for a railroad from Danbury and Sunbury to

Pottsville, where it would connect with the Schuylkill Navigation Company's

canal. Assisted by Mathew Carey and Thomas P. Cope, Nicholas Biddle had been

the leading figure in this move to establish the Danville and Pottsville, or

the Central Railroad as it was generally called. Moncure Robinson located the

line, but funds for its complete construction could not be had. Still, by 1836

it had been run twelve miles beyond Pottsville to Girardville, the site

designated for a town by the great Philadelphia merchant. In 1830 Girard had

purchased at auction from the trustees of the old first Bank of the United

States 30,000 acres in the rich Mahanoy coal region of Schuylkill County. Its

cost to him, including the improvements he had made, was $170,000 at the time

of his death, when he bequeathed it to the City of Philadelphia, probably the

best investment ever made by one of her citizens.

Philadelphians

had not forgotten the importance they had placed back in 1825 on an access to

Erie. The state-owned canal system had been opened to Pittsburgh in 1834, but a

canal to Erie had not been undertaken from that point. Moreover entrepreneurs

now favored railroads, because unlike the canals they did not have to shut down

for the winter months. In 1836 a convention stimulated by Philadelphians was

held at Williamsport to formalize plans for a railroad from Pittsburgh to Erie.

Nicholas Biddle was elected president of the convention, and through his

efforts a charter was obtained for the Sunbury and Erie Railroad with Biddle as

president. Surveys were run and some preliminary work on the road undertaken,

but the Philadelphia and Erie, as it was later known, was not completed until

long after its first president's death.

Meanwhile

the Columbia Railroad's double-track line to the Susquehanna was completed in

1834, with horse-drawn, flanged-wheel coach connections from various points in

the city across the new Columbia Avenue Bridge to an inclined plane up Belmont

Hill, at the top of which the coaches were hooked together for the trip

westward. Later this railroad's tracks were extended from Broad Street down

Market to the Delaware (causing the demolition of the old Court House which had

stood on Market at Second Street since 1708). It was also in 1834 that the

Philadelphia and Trenton's thirty-mile line went into operation. Earlier the same

year the Camden and Amboy Railroad across the river replaced the forty to fifty

stagecoaches that had carried passengers, freight, and the mail overland from

opposite Philadelphia to New York. One remaining line of importance to

Philadelphia continued in progress, the railroad to Baltimore. This road was

built by three companies, with Latrobe laying out the Baltimore-Havre de Grace

section, his former student Strickland in charge from Wilmington to the

Susquehanna, and Strickland's former student Samuel H. Kneass handling the

engineering of the Philadelphia-Wilmington division. The completion of the

first two sections in July 1837 called for a celebration at their juncture on

the Susquehanna, where a steamboat provided the unifying link. The next year the

double-track line from Wilmington to Gray's Ferry was completed, a railroad

bridge built over the Schuylkill, replacing the old Gray's Ferry floating

bridge, and the rails laid to a

depot on Broad Street at Prime (now Washington Avenue). The city now had its

rail access to the South –t he Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore

Railroad.

VIII

With

coal and iron in nearby abundance it was inevitable that Philadelphia in her

transition from a mercantile center should become a manufacturing center. She

had the raw materials and she had the men. John Bristed, in his Resources of

the United States,

published in 1818, noted the city's trend in that direction: "There is no

part of the world where, in proportion to its population, a greater number of

ingenious mechanics may be found than in the City of Philadelphia or where, in

proportion to the capital employed, manufactures thrive better.” Niles'

Register in 1829 noted

the improvement and wealth of Philadelphia, and the extension of her

manufactures: "more than half the business of selling goods in our

commercial cities, for the direct supply of the interior, is in domestic

production. The back shops of Philadelphia are more valuable to her than the

ranges of stores on the Delaware." So great and swift was the rise of

factories in Philadelphia that Peter S. Du Ponceau, in toasting the city in

1829, predicted: "Our good city of Philadelphia - In twenty years the

Manchester and Lyons of America."

The

degree to which Philadelphia had pulled herself out of the doldrums of the

1820s can be appreciated by the surprised comments of a New Yorker on visiting

this "great, beautiful, rich, and self-complacent city" in 1830:

The foreign commerce of Philadelphia

suffers much in comparison and by the all commanding advantages of New York.

But such is the countless wealth of the former city - such her internal

resources and her indissoluable connections with a vast and rich interior -

such the acknowledged superiority of her artists [engineers and mechanics] - of

almost every description - there are so many established and productive

manufactures - she has so much literature, science, and professional talents in

her own bosom-that Philadelphia makes a world in itself, altogether independent

of the accidental superiorities of her rival sister. And her growth within a

few years last past has been more substantial and more rapid than at any former

period. I had expected to see this city decline. But it is no longer a

question. She is destined to rise and grow with the country.

As

these comments indicate, Philadelphia had continued to surge vigorously into

the industrial revolution. Manufacturing and fine craftsmanship were encouraged

by the Franklin Institute's annual exhibits, where all vied for the

"premiums," or medals, awarded. In 1825 the institute offered prizes

for the best specimens in eighty-two branches of manufactures. Mathew Carey,

president of the Pennsylvania Society for the Promotion of Manufactures and the

Mechanic Arts, led the way in making Philadelphia the citadel of high-tariff

theory .

Large

mills for spinning cotton and weaving wool were built with astonishing

rapidity. They were particularly numerous at Manayunk (the old Indian name for

the River Schuylkill), near "Flat Rock," five or six miles above

Philadelphia. In 1820 there was only a toll house there, but by 1825 it was a

thriving factory town, soon boasted of as the "Lowell of

Pennsylvania."" The source of waterpower for mills had always been

there, but it was the transportation facility of the Schuylkill Navigation

Company and its dam and millrace that created Manayunk and helped push

Philadelphia into the first rank in the textile field. By 1828 the city's 104

warping mills employed 4500 weavers and more than 5000 spoolers, bobbin

winders, and dyers.

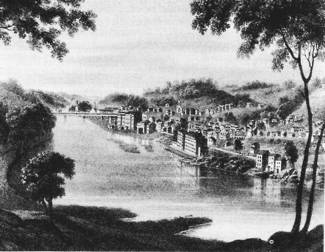

Manayunk, lithograph

published by John T. Bowen (1801 - 1856), after Jobn Caspar Wild (c. 1804 -

1846), 1838.

Philadelphia also excelled in heavy

industry. By 1830 nearly one-fourth of the nation's steel production centered

there, and the city was preeminent in the building of locomotives. Matthias W.

Baldwin led off in this field with his first engine for the Germantown line in

1832, his Baldwin Locomotive Works soon becoming the largest producer in the

country. By 1838, 45 percent of the domestically manufactured engines in use on

American railroads bore his name.

In

some respects William Norris was even more famous than Baldwin. Starting in the

locomotive business in 1832 as a partner in the American Steam Carriage Company,

he moved its shop from Kensington to Bush Hill in 1835, and there built the George

Washington for the

Columbia Railroad. This engine's tremendous power brought him an order for

seventeen like it for an English railroad, the Birmingham and Gloucester. From

then on Norris's foreign business grew rapidly. Many of his machines went to

Austria and elsewhere on the Continent; they were to be found in Cuba and South

America.

Still

another locomotive builder of spectacular attainments was Joseph Harrison, Jr.,

who became foreman in 1835 for Garrett and Eastwick, one of Philadelphia's

pioneer locomotive concerns. Before long the firm had become Eastwick and

Harrison. It is best remembered as the company that moved to Russia to build

the engines and cars needed by the czar.

Samuel

V. Merrick was another industrialist comparable in achievements to the

locomotive builders. In the 1820s he and his partner John Agnew won fame for

their construction of an improved type of fire engine. Next, with John H.

Towne, Merrick established the Southwark Foundry for the manufacture of heavy

machinery and boilers. A founder of the Franklin Institute and destined to be

the first president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Merrick was one of the most

forward-looking men in the city. Many naval vessels were powered by engines

made by his firm, in particular the steam frigate U.S.S. Princeton, built at

the Philadelphia Navy Yard in 1843, the first propeller-driven man-of-war

ordered by the navy.

The

reputation of Philadelphia manufacturers spread far and wide. The city's famous

coachmaker, William Ogle, exported many of his vehicles; his volantes went to South America and Mexico, and a

record exists of his making a carriage for a gentleman in Scotland. In

partnership with George W. Watson, Ogle constructed a factory near the Falls of

Schuylkill, run by waterpower and a marvel of ingenuity and efficiency.

The

making of fire engines was a separate line of business, one in which

Philadelphia became well known as the supplier of southern and western

communities. George Jeffries was one of the principal builders in this trade,

but John Agnew, late of Merrick & Agnew, was outstanding. In 1839 he made

an engine for a company in Mobile that was the largest Philadelphians had ever

seen-a "hydraulian" capable of throwing a stream of water 192 feet.

The sides of its gallery were carved in hold, bronze scrollwork by Samuel

Hemphill. All of its metal ornaments were silver plated, even to the axle

boxes, and much of this was beautifully engraved with appropriate inscriptions

and devices by Gaskill & Copper. The front locker was covered with an

inscribed plate of German silver, the back by a magnificent ornamental painting

by John A. Woodside. The moldings and paneling were blue and black, relieved with

gold.

Foundries

and factories of all sorts proliferated in the Philadelphia of this era.

Cornelius and Company's chandeliers were unsurpassed in beauty, hung in places

as exalted as the United States Senate, and won fame at the Crystal Palace

Exhibition. In a more mundane line, this company provided the countless gas

fixtures required by Philadelphians in the late 1830s - McCalla's carpet

factory at Bush Hill had achieved such a position in the trade that it was

known as the Kidderminster of America. Indicative of the city's ties with Cuba

were twelve sugar refineries, which made Philadelphia perhaps the largest

sugar-refining center in the country, one destined to be later accused of

monopolizing the business. One of the most curious industrial plants of all was

the extensive Dyottsville Glass Works, on the Delaware just above Kensington.

Of its 300 employees, 225 were boys, some not eight years of age.

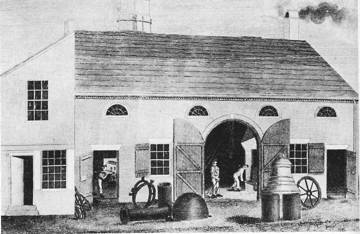

Parke & Tiers Brass

Bell & Iron Founders, Point Pleasant, Kensington, Philada., engraving in Picture of Philadelphia

... (Philadelphia: E. L. Carey and A. Hart, 1831). The foundry, built by C.

B. Parke in 1819, also made sugar mills, soap boiler pans, anvils, and hammers.

T. W. Dyott, Wholesale

and Retail Druggist and Warehouse, northeast corner of Second and Race

Streets, wood engraving from the Philadelphia Directory

and Register for 1820.

View of the Glass Works

of T. W. Dyott at Kensington on the Delaware near Philada., lithograph

probably by David Kennedy and William Lucas after W. L. Breton (c. 177 3-

1855), from Picture

of Philadelphia from 1811 to 1831 (Philadelphia, 1831).

This

kaleidoscopic view presents only a few of the fields in which Philadelphia's

industry developed at such breakneck speed that by 1828 the city was recognized

as the foremost manufacturer in the country. Unfortunately the accomplishment

achieved in transferring the making of products from the home or small shop to

the factory almost totally neglected the human factor involved. The result was

a labor problem of novel aspect to employers, who saw no reason to respect the

"rights" of laborers. They had no rights: if they were dissatisfied,

let them go elsewhere; there were plenty of men available to take their places.

The justness of this attitude was endorsed by the clergy, public opinion, and

the law.

But

the voice of labor began to be heard in Philadelphia. In 1827 the journeymen

house carpenters struck, complaining of the "grievous and slave-like

system of labor.” The reaction of the master carpenters was to advertise for

journeymen in other cities. There

was no security for the workingman. Living in fear of losing his job, he was

crowded into unsanitary dwellings and tenements, working from sunrise to sunset

for pitifully low wages which were subject to drastic reductions. Mill owners

at Blockley and Manayunk expected a fourteen-hour working day, six days a week,

for a weekly salary of $4.33. Vacations were unknown, and July 4 was the only

official holiday.

**********

Soon

came the Panic of 1837, and the ensuing business depression and unemployment so

weakened the bargaining position of labor that the Ten Hour Movement of 1835

became the fond memory of a moment not to be approached again for generations.

At that, the brief success of the movement was illusory. Though the ten-hour

day was the tangible issue at hand, and though the unskilled participated in

the Ten Hour Movement, most of the impetus for the general strike of 1835 came

from skilled artisans, whose basic concern was not the length of the working

day but the loss of their historic status and independence. The independent

artisan of the eighteenth century, who ran his own business from his dwelling

place, was now losing control of his destiny to capitalists who bought up his

products for distribution in a larger, big-city-wide or regional or national

market, and who in the process reorganized the trades.

IX

The

enormous increase in the city's industrial output brought about startling

changes in her population. In 1820 the number of people living in Philadelphia

County already exceeded those in the city proper by 72,922 to 63,713. Over the

years both sections gained in population density, but the county with its new

factory areas grew faster than the city, and in 1840 had outstripped her by

164,474 to 93,652. The old sections of the city began to run down. Few new

buildings went up on the Delaware front; the houses once owned by wealthy

colonial merchants were taken over as tenements or factories as blight set in.

Back from the river more recent residential streets were transformed into rows

of stores as the former residents moved westward. This drift was recognized as

early as 1825 when the Middle Ward boundaries were extended from Fourth Street

to Seventh. By 1830 the center of the city was around Sixth Street, since

37,500 people lived west of Seventh and 43,000 east of

the new dividing line. The 1840 census shows a quickening of the westward trend

- 56,000 inhabitants west of Seventh Street, 37,500 east. Of course the areas

to the north and south were also increasing in population. Southwark, the

Northern Liberties, and Kensington doubled their numbers in this twenty-year

period, while Spring Garden's jumped from 3500 to 28,000.

Surprised

by such changes, an Old Philadelphian recorded in 1828 that "Below South

Street, east of Broad, has recently sprung up a new town. Where last summer the

boys played, there are now solid blocks of brick buildings, grocery stores and

taverns [and the] clitter-clatter of the weavers' shuttle." The quantity

of buildings being erected was astonishing. In 1827 more houses were built in

Philadelphia than in any two years previous, and in 1829 and 1830 it was

estimated that 5000 residences and stores were erected in the city and county,

yet rents were higher than ever.

Building

rows of handsome brick houses, three and four stories high, complete with baths

and water closets, was one of Stephen Girard's favorite forms of investment

carried on by him until his death: "He projects and executes schemes with

the courage and ardour of a young man." Examples can still be seen in the

south side of Spruce Street between Third and Fourth. All were high in praise

of Girard's superior and extensive building improvements. "He has been the

means of beautifying this, his adopted city, and of employing large numbers of

respectable artisans, who might otherwise have been thrown out of bread,"

observed a Chestnut Street merchant."

"Philadelphia,"

wrote Nathaniel P. Willis, "is a city to be happy in. . . . Delightful

cleanliness everywhere meets the eye. The sidewalks are washed constantly; the

marble steps are spotlessly clean.... Everything is well conditioned and cared

for. If any fault could be found it would be that of too much regularity and

too nice precision." As Latrobe had observed earlier of Philadelphia

architecture, "so it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall

be." But change was on its way; granite fronts were coming into vogue, and

among Girard's building efforts was the row of houses on Chestnut between

Eleventh and Twelfth, which were distinguished by marble fronts and pillars.

Rich men like Matthew Newkirk, railroad president, bank director,

philanthropist, and, to his guest Henry Clay's dismay, teetotaler, built marble

mansions.

North Side of Chestnut St:

Extending from Sixth to Seventh St., watercolor by Benjamin Ridgway Evans

(fl. 1840- 1855), 1851. The Philadelphia Arcade, designed by John Haviland

(1792-1852) stood between the Columbia House and Bolivar House hotels. The

second Chestnut Street Tbeatre is just east of the Bolivar House. The Arcade

was demolished in 1863.

Of

the three great architects of the period - Strickland, Haviland, and Thomas U.

Walter - Strickland was probably the most outstanding. "He found us,"

said newspaper publisher Joseph R. Chandler, "living in a city of brick,

and he will leave us in a city of marble."" The marble came from

quarries in Montgomery County and owed its perfection in appearance to the

Scotsman John Struthers, unquestionably the best marble mason in Philadelphia,

if not in the country. Strickland's beautiful buildings did much to enhance the

appearance of the city and to provide her with many of her "lions."

His contributions were impressive: in addition to the second Bank of the United

States (1819 - 1824) at 420 Chestnut Street, there were the Naval Asylum, near

Gray's Ferry (1826 - 1829); a new building for the Unitarian church on the

Tenth and Locust site (1828); the Arch Street Theatre, on the north side of

Arch Street above Sixth (1828); the University of Pennsylvania's Medical Hall

(1829) and College Hall (1829 - 1830); the United States Mint at the northwest

corner of Chestnut and Juniper (1829-1833); the Almshouse at Blockley west of

the Schuylkill (1830 - 1834); the Merchants' Exchange on the north side of

Walnut between Third and Dock Streets (1832 - 1834); and the Philadelphia Bank

on the southwest corner of Fourth and Chestnut (1836 - 1837), to mention some

of the most notable. Of these, along with the Bank of the United States, only

the United States Naval Asylum and the Merchants' Exchange still stand.

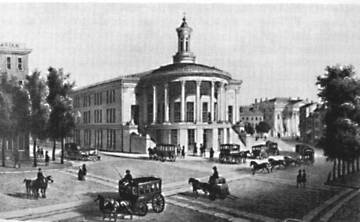

Merchants' Exchange, lithograph

by Deroy after Augustus Kollner (1813 - 1906), 1848. The Exchange, designed by

William Strickland (1788- 1854) in

1832, is now part of Independence National Historical Park.

John

Haviland's first important building was the Philadelphia Arcade, which,

patterned on London's Burlington Arcade, owed its inception as the city’s first

office building to the restless energy of Peter A. Browne. Chief Justice

William Tilghman having recently died, his ancient home, formerly the residence

of Gov. Sir William Keith, was torn down and on its site on the north side of

Chestnut Street between Sixth and Seventh Haviland's handsome marble building

was erected in 1827. The tenancy of the ninety stores it housed was sold at

auction, an odd way of establishing their rental value. Peale's Museum vacated

Independence Hall to occupy the third floor. Intretesting as the novel building

was, it turned out a financial failure.

The

year after he completed the Arcade, Haviland, again in conjunction with Browne,

built an even more curious structure, a Chinese pagoda. This nifty pile stood

in a pleasure garden near the Schuylkill at Fairmount, and presented a tower on

the banks of the Ta-ho, between Canton and Hoang-du. Alas, it too was

unsuccessful.

Haviland

achieved his greatest fame in prison design: cell blocks radiating like the

spokes of a wheel from a central administration building. In 1829 he commpleted

Philadelphia's Eastern State Penitentiary at Cherry Hill-now Fairmount Avenue

at Twenty-first Street - according to this plan and surrouunded it with a stone

wall twelve feet thick at the base and thirty feet high, with castellated

towers at its comers and a massive fortress-like entrance. Having demonstrated

his virtuosity in Greek Revival buildings, such as his assylum for the Deaf and

Dumb on the northwest corner of Broad and Pine (1824-1825) and St. George's

Episcopal Church on Eighth Street south of Locust (1822), as well as his familiarity

with medieval fortresses and Chinese temples, Haviland was next entranced by

the "pure Egyptian." His plan for the Museum Building in 1835 was a

transplant from the Nile. In 1839 he designed a building for an insurance

company on Walnut Street opposite Independence Square. This marble Egyptian

edifice so took the fancy of a prominent New Yorker that the architect was

commissioned to do one like it for that gentleman's residence. Haviland's work

was well known in New York. After the great fire in 1835 he received several

major commissions, including the building of the New York Exchange. This

recognition of his worth caused a New York editor to write: "The best

architectural taste in the country is found at Philadelphia, as her public

buildings make manifest. It is not to be wondered at, therefore, that we are

indebted to the American Athens, instead of our own." The Eastern State

Penitentiary; the original Franklin Institute (1826), on Seventh Street south

of Market, now the Atwater Kent Museum; the Philadelphia College of Art and

what is now St. George's Greek Catholic Church; and the much altered Walnut

Street Theatre are the principal Haviland buildings surviving in Philadelphia

today.

Philadelphia's

third prominent architect, Thomas U. Walter, is noted for his Girard College,

erected 1833-1847, but he also built the Philadelphia County Prison in

Moyamensing in 1835 (demolished in 1967). This formidable Gothic stronghold, to

which were transferred the prisoners from the antiquated Walnut Street Prison

was of granite from the Quincy quarries in Massachusetts. Next to it, Walter

built an Egyptian-style debtors' prison of red Connecticut sandstone. Many

churches and other public structures owed their design to him, such as the

Spruce Street Baptist Church at 426 Spruce. In domestic architecture, his

outstanding work was the enlargement of Biddle's "Andalusia," and

"Portico Row," west of Broad Street on Chestnut (not to be confused

with "Portico Square," of similar construction on Spruce Street).

Between 1825 and 1840 Walter and his friends Strickland and Haviland created

more architecturally important buildings in Philadelphia than had ever been

built there before.

X

Although

her appetite for building improvements seemed insatiable, Philadelphia was often

slow in accepting technological advances. For years voices had been heard

vainly urging the establishment of a gasworks. Baltimore, New York, and Boston

had gas plants, but the city Councils were timid. In 1831 they averred that gas

lighting had not yet been brought to the necessary degree of perfection. They

feared health hazards, danger of explosion, nauseous odors, and other perils

and inconveniences. Irritated by this nonsense, Samuel V. Merrick, advocating

gas lighting, was elected a councilman and went abroad to study gas

manufacture. His report resulted in an ordinance establishing a gasworks which

he designed and superintended for several years. This plant was erected on

Market Street next to the Schuylkill and went into general operation in 1836. The

following year the city's principal streets were lighted by gas. Philadelphians

were thrilled with the new light. "This evening," wrote Joseph Sill

in 1836, "was rendered remarkable by the introduction of gas into my store

and private entry of my dwelling ... the most clear, dazzling, and bright light

I ever saw."

Among

other improvements which came to the city in the 1830s were several in

transportation. Until 1833 Philadelphians went about town either on foot, in

private carriages, or in hired hacks. June 1, 1833, brought a new method, for

on that day omnibus service was inaugurated. The William Penn, lineal ancestor of the horse car,

trolley, and bus, started its hourly runs between the Merchants' Coffee House

on Second Street and the Schuylkill. Immediately afterward line after line went

into operation, their gay equipages fancifully painted and individually named -

Stephen Girard, Independence, Lady Washington, Union - until there was scarcely a major

avenue in Philadelphia without its ponderous looking omnibus service. Six years

after the appearance of the William Penn another mode of conveyance, the cab, attracted favorable

comment. Abbreviated from the French cabriolet, the cab carried two passengers

inside and a driver outside on a box to the rear. Philadelphia's "Cab No.

1” was made by Robert E. Nuttle for Joseph M. Sanderson, the genial proprietor

of the Merchants' Hotel on Fourth Street north of Market.

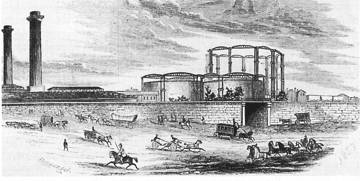

Representation of the

Gas Works, Philadelphia, Market Street at Twenty-Second, drawn by Nicholson

B. Devereux for Gleason's

Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion (1853).

XI

Another

change of the times, brought on by population growth and the inadequacy of

church burial yards, was the commercial cemetery. In 1827 James Ronaldson, type

founder and the enterprising president of the Franklin Institute, opened the

Philadelphia Cemetery (usually called Ronaldson's) on Shippen (now Bainbridge)

Street between Ninth and Tenth, a city landmark until 1950 when it was removed.

Next, the concept of cemeteries set in peaceful, rural settings, modeled on

Mount Auburn, near Boston, and P6rc la Chaise, Paris, became popular. In 1836

Laurel Hill, Joseph Sims's former countryseat on the Schuylkill, was purchased

by a stock company and converted into a beautiful cemetery in the new style.

Before long other similar burial grounds were in operation - Woodlands Cemetery

on the Hamilton estate in West Philadelphia, and Monument Cemetery at North

Broad Street and Turner's Lane, removed in recent years and the grounds

transformed into a Temple University parking lot.

The

elaborate efforts to beautify cemeteries, particularly Laurel Hill where John

Norman was employed as architect, were in the mood of the city's exceedingly

appreciative interest in artistic endeavors. Traditional art activity in

Philadelphia was sustained by the annual exhibitions of the Artists' Fund

Society and of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, as well as by

numerous special exhibitions at Masonic Hall and Earle's Gallery. This was the

Philadelphia of Thomas Sully, her most popular portrait painter. He idealized

his subjects, but he obtained likenesses and painted more Philadelphians than

any other artists. His greatest triumph came in 1838 when he went to England to

paint Queen Victoria. "The Queen, he told me," wrote Samuel Breck,

"was exceedingly affable and granted him six sittings."'

John

Neagle did not obtain as good likenesses as Sully, but his composition was far

more interesting. His portrait of Thomas P. Cope, for example, shows one of

Cope's packet ships in the background, while in the foreground, on a table,

rests the charter of the Mercantile Library Company, of which Cope was founder

and president. Neagle's best known work, Pat Lyon at the Forge, was completed

in 1827. Behind Pat's brawny figure is the cupola of the Walnut Street jail,

where he was imprisoned in 1798 for a crime he did not commit. In his wealthy

old age Lyon insisted on being painted not as the gentleman he had become but

in the role of his early days, a blacksmith.

Rembrandt

Peale, Jacob Eichholtz, and Henry Inman were all prominent portrait painters in

Philadelphia in this period, many of their works being made into prints by John

Sartain, the best engraver of the day. In prolific Thomas Birch, the city

rejoiced in one of the best marine painters of the time, his canvases selling

usually for thirty dollars. Russell Smith had come into public notice when,

failing to gain adequate support for his landscapes, he turned scene painter

and did extraordinary work at the Walnut Street Theatre. In John A. Woodside

the city had one of the best ornamental painters in the country, famed for his

stirring allegories which decorated fire engines. His signs, such as the one

that hung in front of Lukens' Tavern in Kensington - The Landing of Columbus - were unexcelled.

Visiting

artists were invariably entranced by the Fairmount Water Works. In 1834 J. C.

Wild's watercolors of Fairmount were exhibited at the Merchants' Exchange, and

the next year Nicolino Calyo exhibited his large, highly colored city views at

Masonic Hall. Scarce had Calyo been in town a month before he too had his view

of Fairmount, and the ruins of the great fire that burned out fifty-five acres

of New York City had hardly cooled before he was exhibiting pictures of the

disaster.

William

Rush continued in his great tradition. His favorite carvings were ship

figureheads of Indian chiefs. Sometimes they were shown in the act of shooting

an arrow, or in solemn thought, arms folded within a tightly drawn blanket, or

else fiercely threatening with raised tomahawk. But Rush was versatile. When

the ship John Sergeant

slid into the Delaware from John Vaughan's yard in 1831, her figurehead was an

excellent likeness by Rush of Philadelphia's prominent citizen. On Rush's death

in 1833, it was acknowledged that as a carver he had been unequalled. However,

John Rush, his son, carried on capably, carving the figurehead for the mighty U.S.S.

Pennsylvania - Hercules

dressed in a lion's skin, armed with a club.

Whether

the banker's head ornamented the brig Nicholas Biddle at her launching at Southwark in 1838 is

not recorded. She was a first-rate ship intended for the Brazil trade, and not

the first to be named for him. Fortunately a description survives of the Joseph

Cowperthwait, a brig

launched two months later, named for Biddle's cashier. Cowperthwait's bust

adorned the vessel, but not in the usual place under the bowsprit; it was

placed at the stern. To starboard of this effigy in bold carving was the front

of the Bank of the United States, while on the other side were carved

representations of the cashier's books, desk, and the charter of the bank.

Among

the city's many excellent sculptors in marble was Nicholas Gevelot, whose

statue of Apollo, god of music and poetry, was placed in the pediment of the

Arch Street Theatre in 1830. It was Gevelot who carved the angels for St.

John's Roman Catholic Church on Thirteenth Street, and who was commissioned to

do the life-size marble statue of Girard at Girard College. His bronze busts of

Edward Burd and William Strickland delighted Philadelphians who found them on

exhibit at the Louvre in 1836.

To

provide Gevelot with some competition, E. Luigi Persico came to Philadelphia in

1831. Over a period of years Persico immortalized a number of Philadelphians in

marble. Much excellent sculpturing was done by artists whose names are lost.

However, it is known that the brothers Peter and Philip Bardi did the elaborate

capitals for the columns at the Merchants' Exchange, and that the pair of lions

that guard its front were carved by Signor Morelli of 31 Dock Street. At

Struthers's marble yard highly skilled workers provided the city with its most

elaborate mantelpieces, ornamented with delicately worked friezes of grapevines

and Egyptian caryatids. Some of these men, such as Hugh Cannon, later set up

their own studios. John Hill was presumably Struthers's best man, for it was he

who lavishly executed Struthers's masterpiece according to designs provided by

Strickland, the Washington sarcophagus. True proportions were the ideal of the

day. A sculptor exhibiting his statue of Cleopatra in Philadelphia displayed a

certificate testifying to its anatomical exactness, signed by several of New York's

most eminent physicians.

Nicolo

Monachesi, who made Philadelphia his home from 1831 until his death twenty

years later, was a master of painting in fresco. In this medium he decorated

the ceilings of the great room at the Exchange, St. John's sanctuary, and other

Catholic churches. Some of the city's most costly residences bore testimony to

his skill: "This tasteful manner of decorating the walls of noble mansions

is becoming fashionable and seems to offer some encouragement to the fine arts."

For Matthew Newkirk's house he provided a brilliant ceiling of Cornelia, the

mother of the Gracchi, showing her jewels to Capuano. Sidney George Fisher

thought that George Cadwalader's parlors were the handsomest in town; their

walls and ceilings were "beautifully painted in fresco by Monachesi.

One

of the city's most active art patrons was the engraver Col. Cephas G. Childs.

It was he who procured for the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Benjamin

West's masterpiece Death on a Pale Horse. Between 1827 and 1830 Childs published in parts his Views

in Philadelphia and Its Environs,

and in 1829 he became interested in lithography, the city's first lithographic

firm having been established the year before. His major contribution to this

art of inexpensive reproduction was bringing to Philadelphia an expert French

lithographer, Peter S. Duval. Duval, and his competitor J. T. Bowen, turned out

some of the most important lithographic artwork of the times, notably Thomas L.

McKenny's and James Hall's three-volume History of the Indian Tribes of

North America, John

James Audubon's octavo Birds of America, and also the naturalist's Quadrupeds of North America.

A

pictorial process cheaper yet than lithography was at hand. On the afternoon of

October 16, 1839, Joseph Saxton leaned out of a window at the mint, where he

was employed, pointed a contraption housed in a cigar box at nearby Central Hi

gh School, and took the first American daguerreotype. Other inventive

Philadelphians immediately turned their hands to this fascinating innovation.

Ralph Cornelius, a lamp manufacturer, obtained the first picture of a human

face ever taken by Louis Daguerre's process. Dr. Paul Beck Goddard of the

University of Pennsylvania, improved on the technique, and in January 1840 made

the first successful attempt at interior photography. While many rejoiced at

the prospect of cheap pictures, others had cause to mourn. Peter F, Rothertnel,

a promising young portrait painter, gave up portraiture, blaming loss of

business on the daguerreotype. The years that lay ahead were to bring a sharp

decline in the quality of oil painting in Philadelphia, and with mass

production and garish color processes, a falling off in the charm that had characterized

lithographic work of the 1830s.

However, Philadelphia in the 1830s survives visually in the

hundreds of scenes drawn by its artists on stone. The elegance, color,

ostentatious pride, and activity of the day vibrate in these exuberant prints.

Never before had Philadelphians lived in so vivacious a style. The sober veil

of Quaker origins had been rent to shreds; there was a sense of elation and

gaiety in these times of accomplishment, of intense individualism held in check

by pleasant formality, an ordered discipline.

Rowing clubs began to hold regattas on

the Schuylkill in 1834, their members suitably dressed for the sport and their

boats colored to suit their fancy. The Metamoia barge was painted vermilion with a gold

stripe; her rowers wore Canton hats, white jackets trimmed with blue, and white

pantaloons. She competed against the Sylph, orange with red gunwales, her members clad in dark

trousers, pink striped shirts, and red and white caps.

There

had never been so many stirring parades as in this day of fresh and ardent

patriotism. The magnificence of the militia's uniforms was recorded by William

H. Huddy and Peter S. Duval in their U. S. Military Magazine. The triennial processions of the fire

companies were gorgeous, circus-like. Each company had its distinctive dress

(one was garbed as Turks). Their engines and hose carriages, nearly all of them

superbly decorated by Woodside, were drawn on these occasions by horses ridden

by boys in fancy costumes. The officers, carrying silver speaking trumpets,

were preceded by buglers and by standard bearers holding aloft imaginatively

painted banners. Bands of music interspersed the column. Flowers and flags

festooned the equipment. In the 1833 parade the William Penn Hose Company was

led by members dressed as Penn, Indians, and Quakers, accompanied by seamen who

bore gifts offered at the famous treaty.

The

most stupendous parade in these years took place in 1832 on the centennial of

Washington's birth. At 10:30 that morning 15,000 marchers fell into line,

headed by eighteen pioneers, large, athletic men in white frocks and leather

caps, carrying axes. Next came a trumpeter and then the chief marshal, Col.

Clement C. Biddle, whose father had been a marshal in the Grand Federal

Procession of 1788. Included in the parade were the city's officials, the

military, the fire companies, and the various trades, many of them in their

individual full-dress attire. On elaborate floats, printers were busy with

their press and handed out broadsides; the bakers served bread hot from their

oven; tobacconists distributed "segars." The master mariners sailed

up Chestnut Street in an amply manned full-rigged ship. From time to time a

hand in the mizzen chains heaved the lead and announced the depth to the pilot.

Every time the vessel came to a temporary halt her anchor was cast. The

celebration, "the most imposing spectacle that has ever been exhibited at

Philadelphia," concluded at Independence Hall, where William Rawle read

Washington's Farewell Address and Bishop William White delivered a prayer.

Parades

of another sort marked the passing of famous men. On Girard's death in 1831,

Bishop White's in 1836, Dr. Philip Syng

Physick's in 1837, and Mathew Carey's in 1839, those who did not follow

the coffin to the grave lined the streets through which it passed. Girard's

funeral was the largest the city had yet seen; there were 3000 in the

procession and 20,000 watchers. The head of Dr. Physick's funeral column had

nearly reached Christ Church burial ground before its rear had left his house

on Fourth Street. Carey was followed to the grave by unprecedented thousands of

mourners. The interest thus expressed, the ceremonial attention, reflected the

close, personal feelings of involvement that characterized the Philadelphian of

that day.

The

town meeting furnished another outlet for demonstrations of public interest.

When Chief justice John Marshall died at Mrs. Crim's Walnut Street

boardinghouse in 1835, the public met to record its respect. Bishop White

presided and Joseph R. Ingersoll delivered the eulogy. Silver presentations were another form

of tribute and appreciation. On July 4, 1834, Mathew Carey was honored with a

silver service in testimony to his public conduct. The old printer's friends

deemed Carey's "whole career in life an encouraging example, by the

imitation of which, without the aid of official station or political power,

every private citizen may become a public benefactor." Most presentation

pieces were made by Thomas Fletcher, although Carey's came from another

silversmith, R. & W. Wilson. Yet another form of tribute was the

testimonial dinner. The English dramatist James Sheridan Knowles was thus

honored in 1834, and in 1837, 200 of the city's cultural elite dined with Edwin

Forrest at the Merchants' Hotel.

In

these prosperous years, fortunate Philadelphians lived very well, summering at

inland watering resorts or at Long Branch and Cape May. Those who did not go

out of town patronized Swaim's baths at Seventh and Sansom, an elegant

establishment with forty-four baths and showers as well as a swimming pool for

children. For ice cream there was no equal to Parkinson's. where one sat on

sofas and dined off small marble tables. With its marble mosaic floor, its

ceiling a glorious picture of the marriage of Jupiter and Junoby Monachesi,

Parkinson's represented refinement par excellence.

For

bucolic pleasures, the drive to the Falls of Schuylkill was most picturesque,

and the catfish and coffee to be had at the taverns there formed a favorite

meal. Closer at hand, nature could be enjoyed at various botanical gardens and

nurseries, such as Bartram's (run by Robert Carr), Daniel Maupay's, and the

Landreths', which sold seeds and plants all over the country and also to Europe

and South America. In the city proper were the public squares. In 1825 the city

Councils gave them names - Penn, Logan, Washington, Franklin, Rittenhouse, and

Independence. By 1837 when the cemetery on Franklin Square was obliterated,

they had nearly all been extensively improved with walks and plantings. On

Washington Square fifty varieties of trees flourished. Philadelphia's interest

in flowers and shrubs was stimulated by the founding of the Pennsylvania

Horticultural Society in 1828 with Horace Binney as president.

The

city offered a wide range of entertainment, the most rewarding of which was a

visit to the new marble Museum Building, opened at Ninth and Sansom on July 4,

1838. After ten years at the Arcade, the Peale family collection was moved to

this location, where could be seen some of the best exhibits in the country.

Its "grand saloon," 233 feet long, 64 feet wide, and a towering 32

feet in height, was said to be the largest room in America. In its center stood

the prodigious skeleton of Peale's mastodon. In one of its lower rooms was Nathan

Dunn's Chinese Collection, which he had assembled during a long residence in

Canton. Some seventy to eighty life-size figures in costumes from that of

mandarin to coolie, Chinese rooms and shops, landscapes and portraits, ship

models and numerous other objects illustrated the arts, manners, pleasures, and

characteristics of the celestial race. A block from the museum, the Assembly

Building offered the best facilities for balls and receptions. Its great hall,

with its immense mirrors, rich pilasters, Corinthian capitals, and gilded

moldings, was likened to Aladdin's palace. Here Signor Antonio Blitz, one of

the most popular entertainers of the time, performed with his trained birds,

his sleight-of-hand and magical tricks, and his feats of ventriloquism. And as

for the theater, staid Philadelphians were surprised to note that in 1840 there

were seven of them in nightly operation.

The

glamor of the stage had its attractions for the city's men of letters. Dr.

Robert Montgomery Bird, without doubt Philadelphia's ablest literary figure,

created the role of Spartacus in The Gladiator for Forrest. In this part the famous

thespian won ovations in New York, Philadelphia, and London. By 1853 this play

had been performed a thousand times. Another distinguished actor, Junius Brutus

Booth, acted the principal role in Sartorius, a drama by David Paul Brown, one of the

city's leading orators and criminal lawyers. Showing unusual modesty, Brown

thought that it was not so remarkable that he "should have written two bad